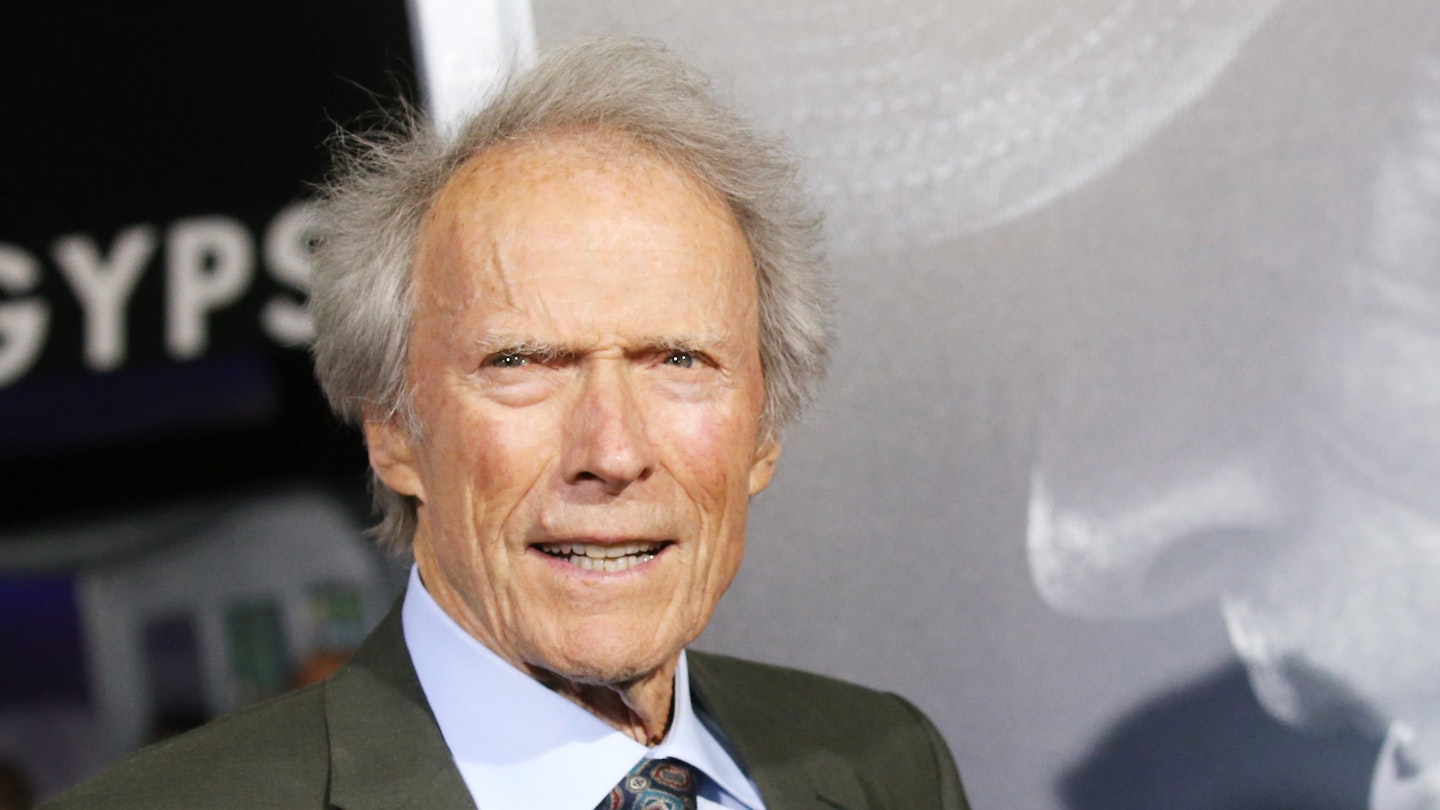

Everyone always notes that The Shootist was the perfect elegiac last role for John Wayne to play, the grizzled, terminally ill gunman poignantly strapping on his shooters for one last showdown. Clint Eastwood is without doubt familiar with that film; it was made by his mentor and friend Don Siegel between Don and Clint’s collaborations on Dirty Harry and Escape From Alcatraz. There is speculation that the 78 year-old Eastwood’s irresistible turn in Gran Torino may be his final role as an actor. We hope he will be hale, hearty and helming fine films for a fair few years yet. We even suspect he could be tempted in front of the camera again if a plum part presents itself. But it certainly feels as though he took a long, close look at projects with an eye to bringing down the curtain on his own iconic acting career of 53 years with just such an apt and valedictory role as Wayne found.

If so, he’s struck 24-carat gold with Nick Schenk’s screenplay and a hellacious turn as disgruntled Walt Kowalski. For a while you may think this picture is about Dirty Harry as an OAP. The story begins with the funeral of Walt’s beloved — and evidently saintly — wife. As soon as we see him standing militarily erect by the coffin, it’s clear he looks not so much mournful as furious, at everyone from God and the ridiculously youthful, sincere Catholic priest, Father Janovich (Christopher Carley), down to his obnoxious grandchildren. While Walt listens to prayers and platitudes his tightly controlled wrath begins to emanate from his core in a low, feral growl. (Although his ire is understandable, it is surely improbable that his two sons, however strained their relationships with their old man, would let their sulky children come to their grandmother’s funeral dressed as slobbishly and sluttily as this clan are. The granddaughter who blatantly can’t wait for him to die so she can get his car even sends text messages during the funeral.)

Walt is a decorated Korean War veteran and retired auto worker at the Ford plant where he helped assemble the now-classic car he keeps in pristine condition in his garage. The car and his old dog Daisy seem to be the only things left in the world he cares to talk to. Mostly he fills his days with DIY, when he isn’t sitting on the porch swigging beer and grumpily surveying the rundown Detroit neighbourhood he considers blighted by the influx of immigrants and multiple ethnicities. It doesn’t seem to have occurred to him that they have been as betrayed by the promise of the American Dream as he feels he has been. The family next door are Hmong, the hill people from Laos and Vietnam who were persecuted and finally allowed to settle in the US because they aided the Americans during the Vietnam War. But Asians are all lumped together as ‘Chinks’ and numerous other nasty words to Walt, who has horrible memories of Korea and is mad as hell that one of his sons drives a Japanese SUV.

The mild-mannered teenager next door, Thao (Bee Vang, bearing up beautifully in Eastwood’s aura), is under heavy pressure to join an Asian gang of thugs who coerce him to boost Walt’s Gran Torino. This is when they find out the ornery old coot is locked and loaded. When an ensuing contretemps between the gangbangers and shy, bookish Thao spills into Walt’s tidy garden, his dander really gets up. Trust us, when he tersely commands through gritted teeth, “Get... off...my... lawn,” only the dimmest offender would stick around. He doesn’t need his youth or even the gun to be as mean and tough as a man can be. He only has to turn up scowling and squinting to telegraph menace and the conviction he can back it up. “Ever notice how you come across somebody once in a while that you shouldn’t have messed with? That’s me.” The Hmong neighbours, pathetically grateful Walt has saved Thao’s bacon — not what he had in mind — press unwanted gifts on him and insist Thao do chores for him to make amends. Grudgingly Walt puts the kid to work, decides rather hilariously to “man him up” and thaws just a degree or two under the cheerful, confident chatter of Thao’s sassy, engaging sister, Sue (Ahney Her, who is a delight). He doesn’t get too chummy, mind, insisting on addressing Thao as “Toad” or “Eggroll”.

Walt’s an equal opportunity abuser. His extensive vocabulary of racial slurs and epithets includes words no-one outside the Aryan Nation has probably heard out loud for decades, and he’s not afraid to hurl them indiscriminately and with insane, death-wish insensitivity at any gangbanger, refugee, burglar or little old lady who crosses his path. He even publicly berates the persistent young priest (who promised Walt’s wife he’d put Kowalski right with Jesus and is incautiously determined to follow through) with an embarrassing sexual aspersion. When he confronts a group of young black wastrels hassling Sue, he nonchalantly offers them a greeting so gasp-inducing they are as disbelievingly thunderstruck as the audience. He shouldn’t be funny — and Eastwood keeps himself tightly in check, never allowing Walt to slip into anything close to nice, let alone charming — but he is, so awesome and awful and outrageous he’s the most fascinating misanthrope since Jack Nicholson’s homophobic misery-guts in As Good As It Gets.

In lesser hands this plot could have a tritely familiar air. It could very easily have dwindled into crude comedy or descended into an obvious sentimentality. But Eastwood the actor grabs you with his first growl and has you between his clenched teeth for the duration. Eastwood the director shapes the picture into another of his latter-day contemplations on violence, vengeance and racial tension in American culture, and a moving face-off with the prospect of death to boot. His direction is lean, clean and spare, with no fat and no sagging. It’s an extraordinary piece of work to have done back-to-back with Changeling — obviously smaller in budget and cast, much simpler in design, confined to a handful of settings, but just as meticulously, astutely executed.

Eastwood has also distilled into Walt Kowalski his life in films, the character and his distinctive way with a phrase a nod to every memorable hardass Eastwood has portrayed, from The Man With No Name and Harry Callahan to Will Munny. Walt is no Magnificent One, cleaning up the ’hood for the poor immigrants he’s taken to his awakened heart. Oh no. It flirts with that, but subtly, smoothly shifts gears from the Alf Garnett act and the odd-couple bonding bit into something more painful, affecting and meaningful with a totally unexpected twist that really is magnificent, befitting both the character and Eastwood’s career.

And do not rush off at the end. Anyone who vowed never to forgive Eastwood for his insecure song stylings in Paint Your Wagon will be startled into chuckling, affectionate submission at the end credits by the appropriateness of Clint’s gravelly delivery of the self-penned title track (co-written with son Kyle and Jamie Cullum).