Ripped from the headlines, Good Kill is as terrifying as it is timely. Reuniting with his Gattaca compadre Ethan Hawke, writer-director Andrew Niccol drills down into the moral and psychological murk of drone warfare with a cool head and a tight grip. The filmmaker is cleaving to his previous sci-fi vibes (the dystopian feel of Gattaca, the omnipotent surveillance of The Truman Show) but locating it firmly in the here and now. Good Kill makes it painfully clear that death by joystick is no longer the province of the PS4.

The movie is at its best in the hothouse environment of the bland drone cubicles. Early on, the film is so forensic and fascinating about detailing the process of remote strikes that by the end of the movie you feel like you could tackle one yourself. This pays dividends when Hawke’s pilot Thomas Egan is co-opted to fly missions under orders from the CIA (the cold disembodied voice on the phone is played by Peter Coyote) as the off-the-record missions and practices become increasingly dubious. The cool calm routine we’ve become accustomed to takes on a more tense sinister edge.

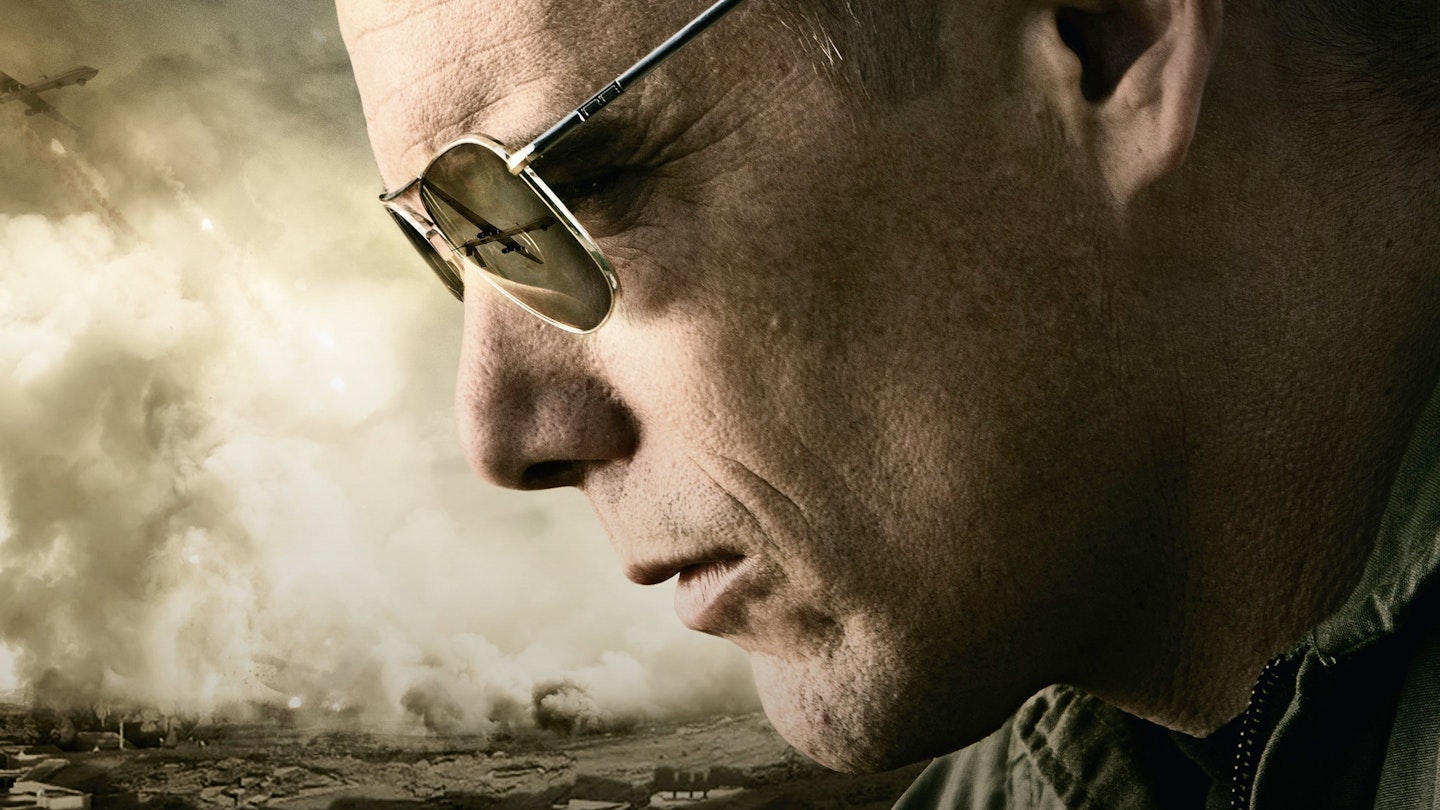

Hawke, on a roll after Boyhood and Predestination, is terrific. In green fatigues and Aviator glasses, Egan is Maverick past his prime, wrestling with the after-effects of modern warfare now the thrill and immediacy of actual combat have been taken away. Hawke makes his slide from hard as nails military type to self-loathing wreck believable and affecting. January Jones plays effective riffs on her housewife-in-meltdown mode from Mad Men and Zoe Kravitz is a sparky presence as Egan’s equally troubled co-pilot.

Some of it feels over-egged; a sub-plot involving Egan’s involvement with a victimized villager is a tad trite, but for the most part it is a model of tact and complexity. Niccol keeps his political posturings to a minimum and is alive to the thin line dividing so called terrorists and so called peacekeepers. For a film about the distancing effect of technology, it keeps things very human.