Since 1999, when Leonardo DiCaprio signed on with America's greatest living director, expectations have slipped from 'eagerly-awaited', to 'long-awaited', to worryingly 'long-delayed', as Gangs Of New York's US release moved from December '01, to July, then December '02.

It arrives here burdened with gossip of hostilities and an awareness that there's been a lot of fiddling about, all of which gave Di Caprio time to make a Spielberg movie that's opening almost simultaneously.

Masterpiece or muddle, then? Truth is, Scorsese's latest spectacle is something of both. This dark, provocative 19th century epic - with its gorgeously sinister cinematography (by Michael Ballhaus) and stunning period detail - is signature Scorsese. Ambitiously he extends his journey through the violence in America's social fabric back in time to argue that, to quote the poster, the great democracy was born (bloodily) in the streets, and is still kicking and screaming to this day.

This is a bold, brave look at history as it is not taught, brutally contradicting the 'melting pot' fable of the American Dream. These huddled masses are clawing for survival in a cesspit of poverty, cruelty, corruption and greed, ultimately to be engulfed in the Draft Riots, America's worst mass explosion of civic unrest. Gangs' romantic fictional plot - running through the bigger, factual backdrop - is traditional. A poor urchin witnesses his father's gruesome murder by the white Anglo-Saxon Protestant lord of the 'hood, grows up in a grim institution, returns to avenge his father, falls for a tough lovely, and becomes the Moses of his squalid, barbaric patch of Manhattan. This is unnecessarily drawn out when we all know roughly where it's going. Amsterdam's buddy, for example (E.T.'s Elliott, Henry Thomas, as Johnny), might as well have 'I'm going to betray you because I covet your girl' tattooed across his forehead.

The second half of the film, however, feels rushed. The narrative hiccups and jumps around as peripheral characters and wider ideological, racial and religious conflicts envelop the local, personal turmoil. Bewilderment or boredom, choose one.

The film doesn't disappoint, however, in its breathtakingly cinematic - and frequently horrific - set-pieces. Most memorably, a remarkable single shot follows newly-arrived, ragged, starving immigrants disembarking, issued with citizenship, sworn into the army, thrust into uniform and marched up the gangplank of a Federal ship as coffins of the war casualties are unloaded.

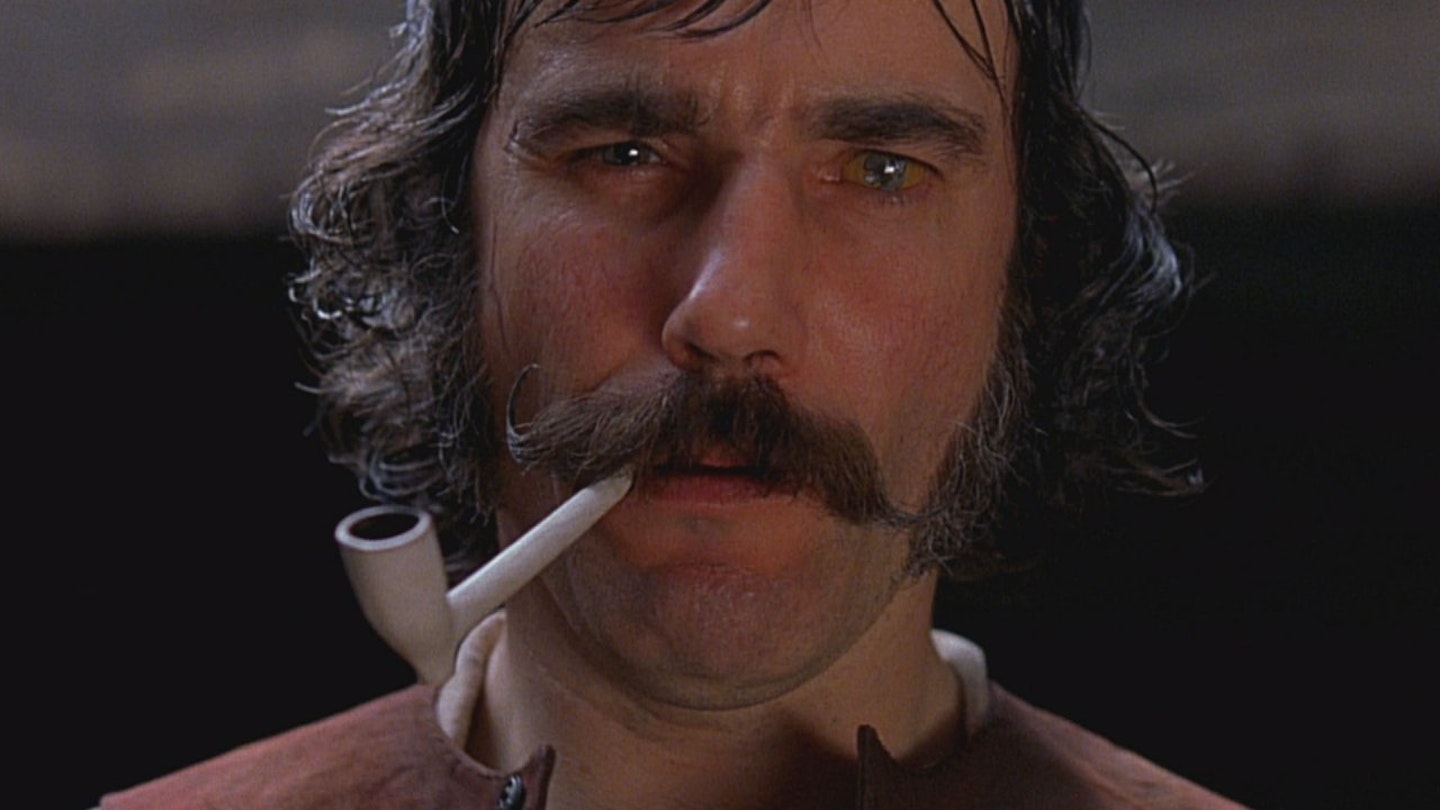

Daniel Day-Lewis resists the temptation to twirl his handlebar moustache, but his superb impersonation of Robert De Niro (once set to play the Butcher) is sociopathic, show-stealing Grand Guignol, as he ruthlessly wields cleavers, knives and power with disturbing expertise. A xenophobic monologue he delivers seated by Vallon's bed, draped in a bloody Stars and Stripes, is absolutely hair-raising. DiCaprio, meanwhile, looks the heartthrob but also provides the vital emotional engagement. Diaz is implausibly contemporary and clean for her role, but valuable in the erotic stakes.

It has to be said that funny hats and voluminous checked pants distinguish this decade as a particularly absurd fashion era for men. The gangs look like satirical dastards in a nightmare of atavistic street fights and sadistic entertainments created by a mad Charles Dickens on a very bad trip.