Michael Haneke first made Funny Games in 1997, in his native Austria, and though that shocker certainly put arthouse audiences through the wringer, it was never really seen by the people it was intended to provoke. A decade later Haneke chose to remake the film for America, following the original with an almost verbatim English script. The surprise is that it works: though the camerawork isn’t shot for shot, the new-look Funny Games not only keeps the integrity of the original but looks set to have a life of its own.

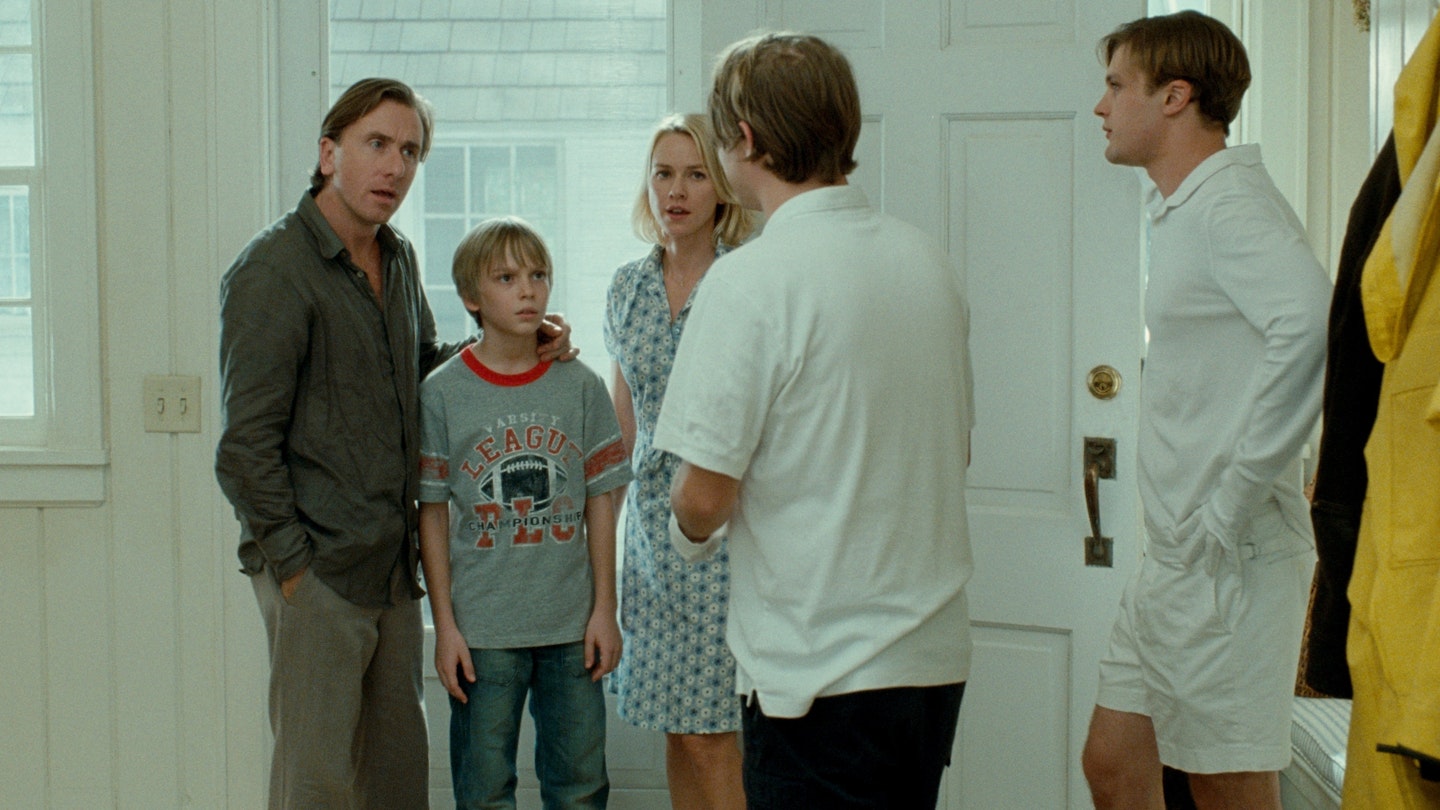

Key to its success is a fantastic performance by Michael Pitt as Paul, one of two preppy kids who turn up on George and Anna’s doorstep one day and turn their lives into hell. Not since Malcolm McDowell in A Clockwork Orange has deadly amorality worn such a cheerful mask, and it’s a measure of his performance that even the more macho George (Tim Roth) is emasculated by the unimaginable horror of his psychopathic possibilities. As his sidekick Peter, Brady Corbet is pretty special too, playing the role as a sinister stooge - like Igor to Baron Frankenstein while suggesting he might also have some sadistic specialities of his own hidden up his tennis-shirt sleeves.

While Pitt and Corbet clearly have a lot of fun, there’s also hard graft going on here, which is where Naomi Watts, Roth and extraordinary newcomer Devon Gearhart come in. Watts, especially, gives her all in a mostly reactive role, moving from chirpy neighbour to protective, narky wife-and-mother to helpless, almost catatonic, victim. Roth plays it low-key, taken out physically by a broken leg and mentally exhausted by his unfathomable tormentors.

It’s a measure of these turns that Haneke’s film really doesn’t need the gimmick that made it stand out ten years ago. At several intervals through the film Paul directly addresses the camera, actually discussing the finer points of the film’s ongoing narrative with the viewer. In the remake these moments still jar, but not necessarily in a good way. After all, the new Funny Games will most likely be seen by genre audiences who get its self-reflexive nature and the games it plays, not just with its characters but with the conventions of thrillers, showing soberly and bleakly how, in real life, the cavalry often never comes.