Since his departure for Hollywood in 1939, Alfred Hitchcock had only made two films in Britain and neither Under Capricorn nor Stage Fright had been particularly impressive. So, the 73 year-old Londoner clearly set out to atone with what would prove to be his penultimate picture. Opening, like Young and Strange exactly 40 years earlier, with a body floating down the Thames, Frenzy was not just a dark homage to the bustling city of Hitchcock's youth, but it was also a scrapbook of the themes and stylistic traits that had become his trademarks.

The title came from a discarded screenplay of the mid-1960s (aka Kaleidoscope) that Hitchcock had been developing with Howard Fast, before Universal decreed that no one would want to see a film about a gay psychopath. But the story of a necktie strangler who stalks the backstreets of Covent Garden was adapted from Arthur LaBern's novel, Goodbye Piccadilly, Farewell Leicester Square.

The emphasis on the mind, motives and methodology of a killer links Frenzy with Shadow of a Doubt, Strangers on a Train and Psycho. But the empathy with the innocent accused also recalled The 39 Steps, I Confess, The Wrong Man and North By Northwest. However, Hitchcock managed subtle personality twists in both Bob Rusk and Richard Blaney to ensure that neither villain nor hero was as sympathetic as Bruno Antony and Norman Bates or Richard Hannay and Roger Thornhill.

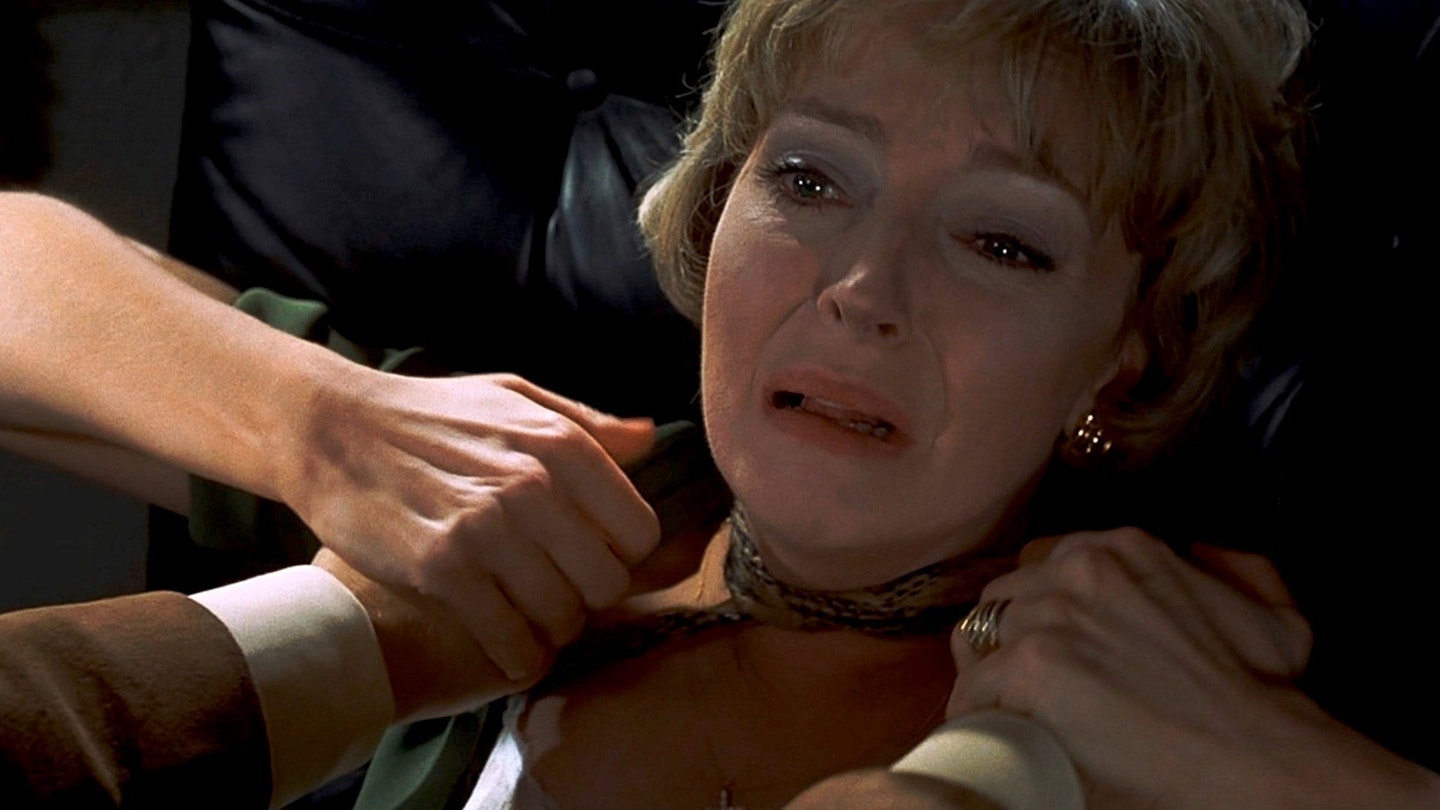

Typically, however, Hitchcock couldn't resist some grim comedy, hence the crack of Anna Massey's rigor-mortised fingers being echoed by Vivian Merchant (the wife of detective Alex McCowen) carelessly breaking crispy breadsticks while discussing the case over dinner. Hitchcock was accused of misogyny for his comparison of Foster's first on-screen victim, Barbara Leigh-Hunt, with a quick lunchtime snack and his second, Massey, with a sack of potatoes. But such callousness chillingly reflects the dog-eat-dog society in which the film is set, as well as its all-pervading atmosphere of decline, decay and disappointment.