Scottish director Mark Cousins is not known for entering into things lightly; without commitment. This, after all, is the man who made the 15-hour documentary The Story Of Film: An Odyssey in 2011.

It’s a commitment repeated — if not in length, then in depth — in The Eyes Of Orson Welles, his at times dream-like, obsessive quest to discover the visual artist he argues was at the heart of the Orson Welles the public is more familiar with.

Cousins doesn’t talk about Welles, he talks to him, via a long, very personal love letter that creates the narration of his voiceover. The intimacy is startling, disorientating. Like listening in on a lovers’ phone call, hearing the conversation only ever meant for two sets of ears. Or reading the letters meant for two sets of eyes. Cousin’s smooth, lilting, Scottish brogue manages to seduce — both you and you feel, somehow, even in death, his subject.

The film has a surprising, unnerving current-day relevance.

Orson Welles painted, drew and sketched for most of his life, starting at just nine years old, though much of his output was unfinished, or what appeared to be various partial states of completion. Cousins fills in the gaps, tracing thick lines over the ones left thin and slight.

He blends old photographs, film clips, interviews and a video diary as he retraces Welles’ steps across Ireland, Spain, Morocco, Paris and Arizona. Welles the actor and Welles the director both presented as extensions of, products of, his life as an artist. It’s a compelling argument, made steadily, gradually; a clear line being drawn between his charcoal sketches, stark paintings and fully realised on-screen performances. The scale and scope of Welles’ creative vision blooming into being before your eyes over the course of the film.

For a documentary on a man who died more than 30 years ago, the film has a surprising, unnerving current-day relevance, with Cousins describing Welles’ resistance of fascism during his lifetime. It’s hard not to imagine what Orson Welles the artist, the man, would make of 2018.

There are undoubtedly moments which feel deeply, even desperately, indulgent. A sequence in which Cousins writes a fanciful (imagined) reply from Orson Welles to him grates with contrivance and bursts with ego. But you can forgive a passionately uncynical Cousins these moments — not least due to his coup of securing a wealth of unseen art from Welles’ youngest daughter, Beatrice. It’s this which makes you feel as if you’re seeing Orson Welles anew, with fresh, grateful eyes.

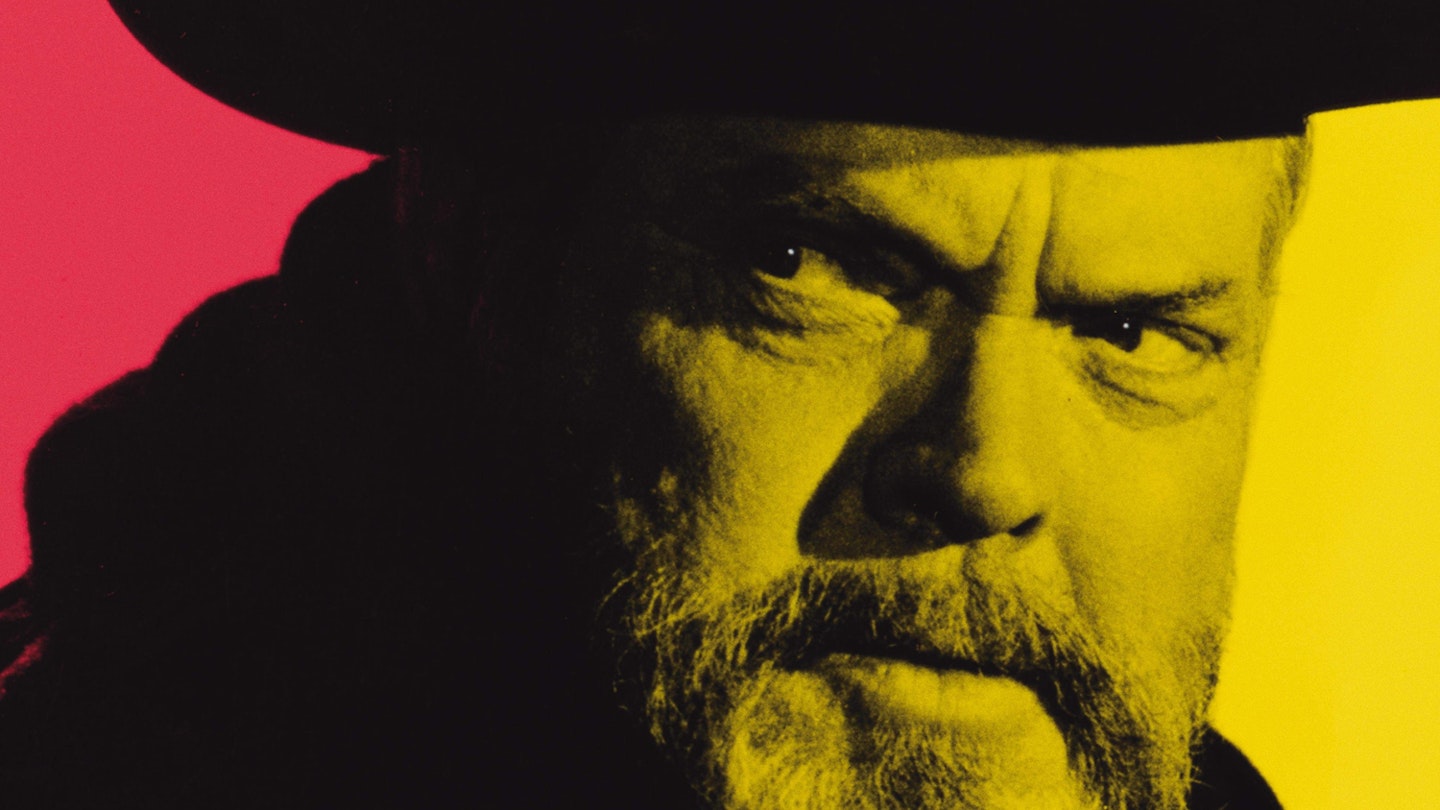

“Who were you?” Cousins asks Welles, repeatedly revisiting one striking image of his subject, untouched yet by age, lying on a bed, eyes blazing, locked on the camera. And with this documentary you feel that he, and we, are one big step closer to finding out.