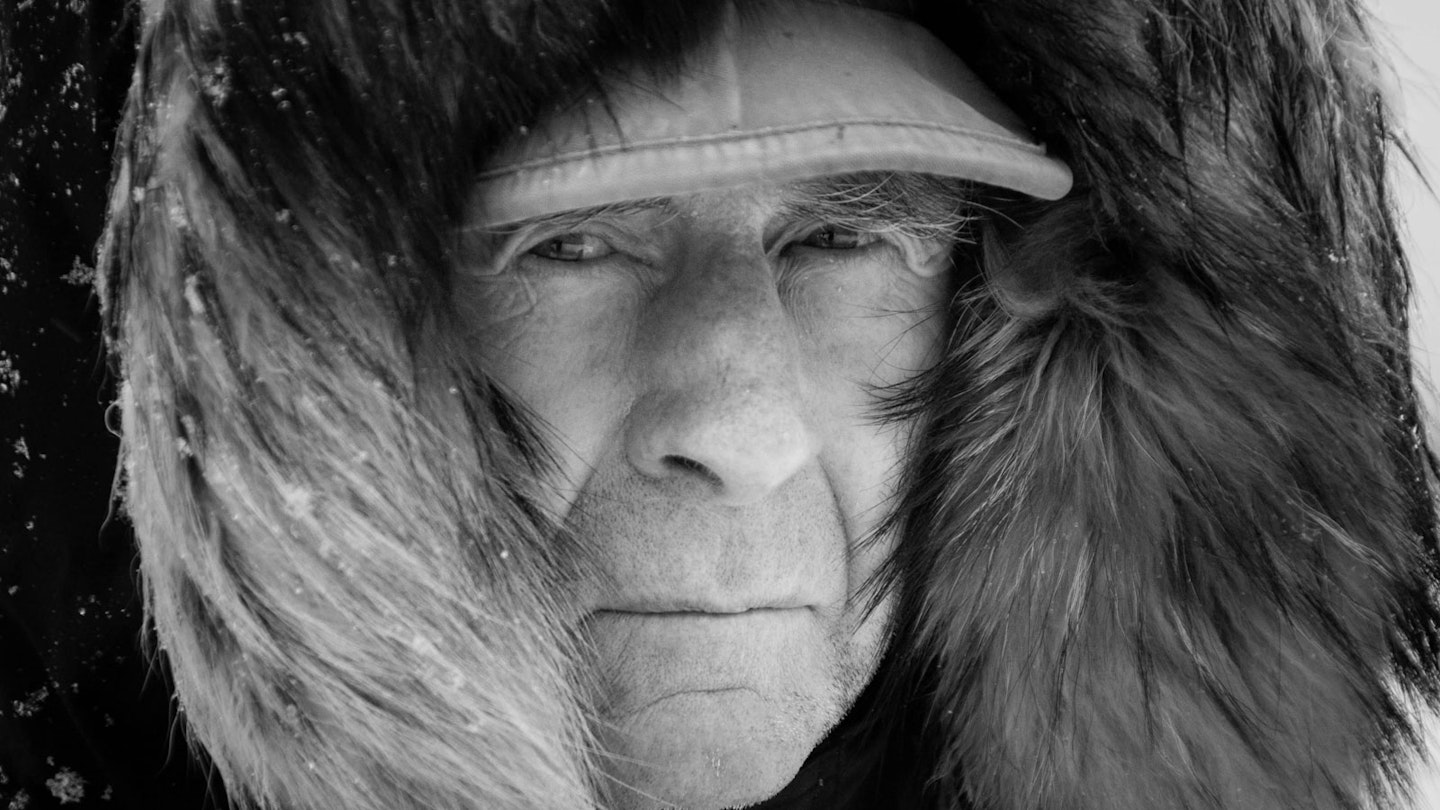

Matthew Dyas’ film about The World’s Greatest Living Explorer™, Ranulph Twisleton-Wykeham-Fiennes, has the madness of a non-fiction Fitzcarraldo. Like Klaus Kinski’s wild-eyed visionary, Fiennes proves that dreamers can move mountains through sheer will, stubbornness and ingenuity. Dyas, who has a background in natural history filmmaking, etches Fiennes’ story briskly through archive footage and disembodied voices, but interjects it with footage of Fiennes’ life today. As such, Explorer is an enjoyable survey of a fantastic, almost unbelievable CV, but scored with human moments and an undertow of sadness.

The biographical high points of Fiennes’ eventful life are a documentarian’s dream: chucked out of the SAS after blowing up the set of Rex Harrison’s Doctor Doolittle; ran night raids for the sultanate of Oman; traversed the North and South Poles; completed seven marathons on seven continents in seven days (four months after suffering a heart attack); and became the oldest Briton to scale Everest. The film doesn’t skimp on the sensational details — on one expedition, he lost the tips of four fingers — but is also astute enough to reveal Fiennes’ self-awareness of the way he is perceived. During the pre-publicity for the Transglobe Pole to Pole trek, he tells his team to dial down their public-school backgrounds. “White-privilege folly” is invoked, but the film doesn’t really engage with these notions.

Dyas’ filmmaking, especially in the early scenes, is artful, employing a creative use of sound design.

Even around these peaks, there are lots of stories — he reached the last six to play James Bond when Roger Moore was cast —and they are told in broad, colourful strokes. But what is more affecting is the portrait of his 48-year relationship with childhood sweetheart Ginny — he used to leave secret love letters for her in a tree trunk — who became a driving force in his life until she passed away of cancer. He admits it’s “the only topic that makes me emotional” and Fiennes’ coming to terms with her absence, especially given his stoicism, is undeniably moving. Also touching is the snapshot of Fiennes today, driving up and down the country to do personal appearances as a means to “pay the gas bills”, sleeping in his battered-up car in-between signings, asking director Dyas what the word “woke” means and just frustrated with the limitations of his body and health (as a jogger runs by, he ruefully offers: “Those were the days”).

Dyas’ filmmaking, especially in the early scenes, is artful, employing a creative use of sound design (even if it is sometimes difficult to keep track of all the disconnected voices). There’s little in the way of probing analysis or insights into what makes Fiennes tick, but Explorer makes for a compelling testament to one man’s will to push himself to the limit. And then some.