Mark Jenkin is a filmmaking force. The Cornish writer-director has, since 2002, cultivated a unique style of experimental, hand-cranked short films, all of which culminated in the BAFTA-award-winning 2019 feature Bait: a stupendous black-and-white drama about gentrification tensions in a Cornish fishing village. Playing with cinematic grammar while staying firmly in his West Country backyard, Jenkin managed to create something that seemed both plucked from the past and thrillingly new — a trick he has now repeated with his latest film.

Enys Men (pronounced “Ennis Main”, meaning “Stone Island” in Cornish) is a striking, haunting sophomore feature that cements his signature style, while branching into new territory. Bait’s black-and-white aesthetic evoked early silent-era cinema, yet it had a modern setting (Airbnbs swamping Cornwall has been the source of much grumbling); Enys Men, meanwhile, is set half a century ago, but sees Jenkin move into colour photography, albeit still shot on 16mm, and still carefully crafted via traditional hand-made methods.

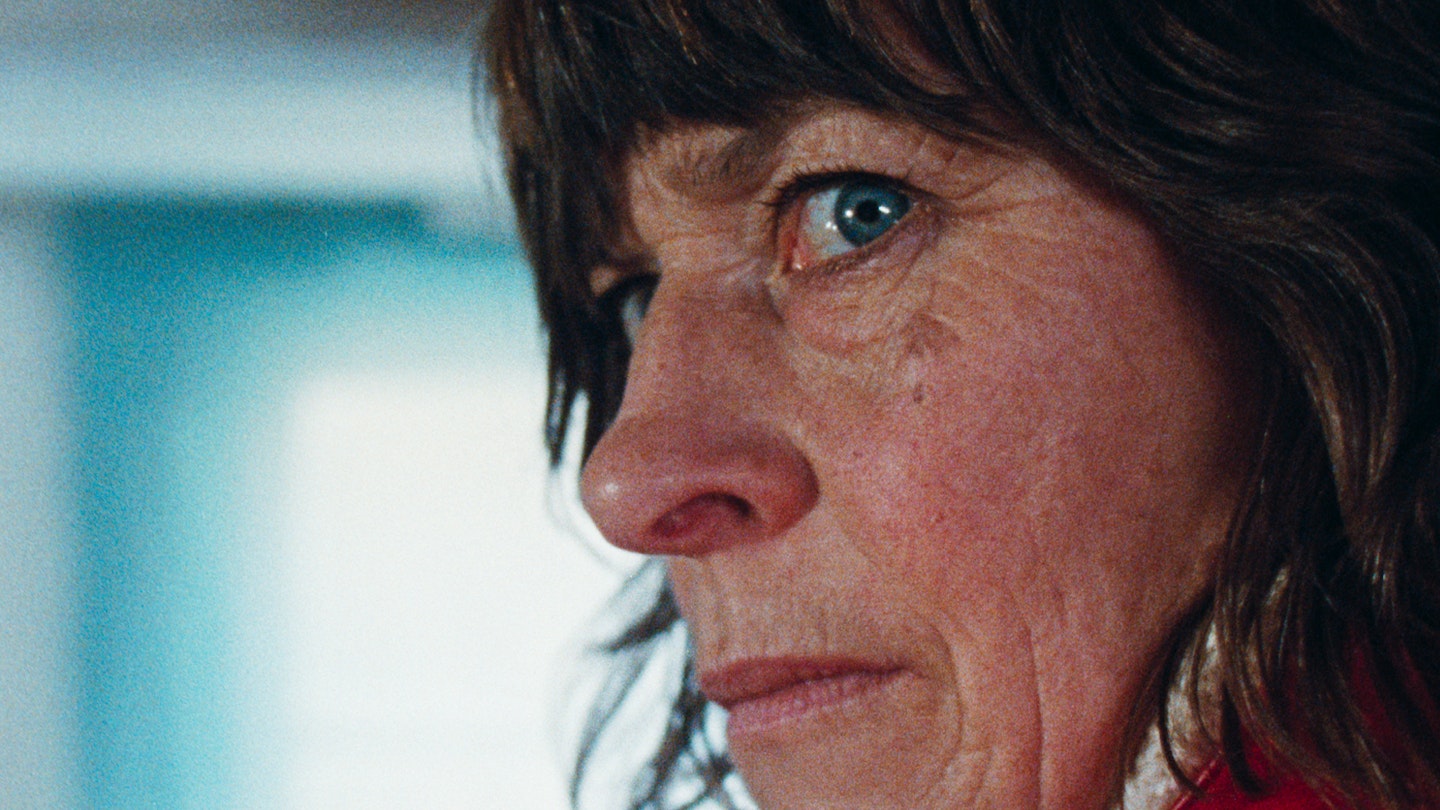

The move away from black-and-white is really striking, the grade, grain and finish meaning some colours really pop — especially the bright-red rain jacket of the film’s lead character, the never-named ‘Volunteer’ (Mary Woodvine). It’s a visual motif which (though according to Jenkin coincidentally) has echoes of Nicolas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now, another psychological horror about grief and loneliness, which happened to be released in the year this film is set.

The experimentation that is Jenkin's hallmark is matched with a new narrative experimentation.

It feels specific to 1973, but then — like Bait — the lo-fi approach gives it a timeless feel, too, as if the entire film were just a lost reel of found footage, washed up on a Cornish shore. The pacing is quiet and deliberate: we watch as the Volunteer keeps a carefully kept ritual, leaving her rickety cottage on a tiny island every morning, to check on the progress of a cluster of presumably rare wild flowers, measure the soil temperature, and record her findings in a pencil-written log book. (Her daily update, “No change,” feels like this film’s answer to, “All work and no play...”)

Naturally, any disruption to that ritual — played out again and again — leaves a brooding sense of unease. (Perhaps most troubling of all is when the tea supplies run out; this is a British horror, after all.) The experimentation that is Jenkin’s hallmark — strange static close-ups of unmoved faces, disorientating editing — is matched with a new narrative experimentation, when the Volunteer’s metaphysical reality becomes fuzzy, and visions of milkmaids, singing schoolchildren, and even the Volunteer herself begin to inexplicably appear.

There are hints of the collective grief that comes with a coastal community losing souls at sea, and a paganistic connection between the flowers and the Volunteer, the ghosts of the past bubbling up through the roots. But logical explanations are only ever lightly implied. In the proud traditions of English folk horror, Enys Men can be a challenging experience; leaving you with a sense of something ancient, yet also, in Jenkin’s ambitious telling, entirely fresh.