There are a number of powerful images in Peter Weir's end of the millennium masterpiece but one that really sticks in the mind, capturing as it does the central theme of The Truman Show, occurs only for a brief moment in the middle of a montage as "creator" Cristof describes Truman's development. We see a toddler in a playpen gazing upwards, apparently fascinated by a children's mobile. Fluffy shapes spin around to a tinkling nursery rhyme. But at the centre of the toy dangles the menacing shape of a camera lens and it's to this that the child's curious, slightly worried expression is directed. If one of the many themes of The Truman Show is betrayal then it is this shot that sums it up more eloquently than any other.

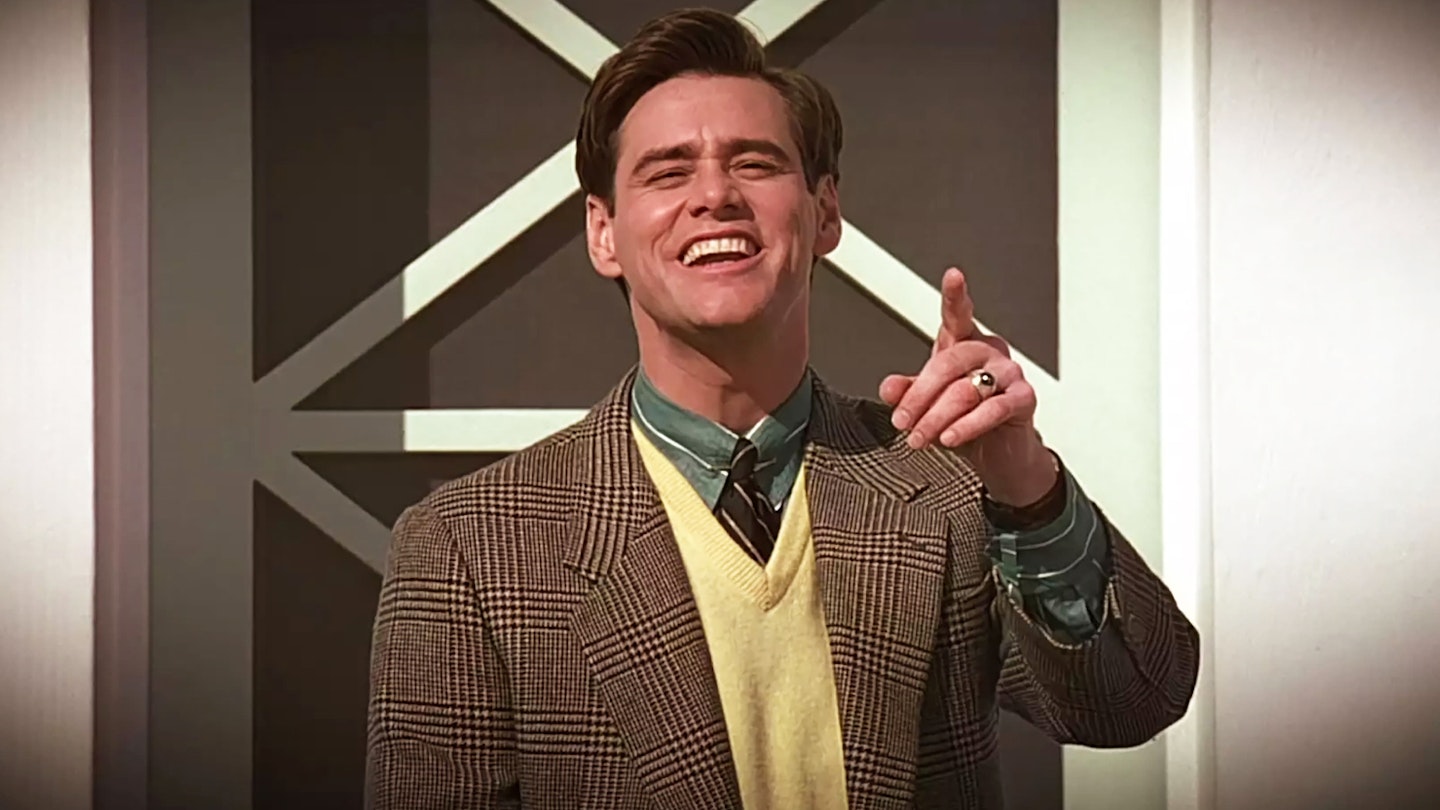

It's one of the ironies of science fiction movies that while they concern themselves with either the future or at least technology that doesn't yet exist, they generally have more to say about what's going on in the present than any of the other genres. By the end of the 90s, media saturation, anxiety over privacy, encroaching media power and, with virtual reality, the increasingly unreliable nature of the real world were the prevalent preoccupations. Peter Weir's film was not alone in broaching these themes. The Matrix took a different approach for a different audience. But it is Weir's film, which is certainly science fiction in that the technology required to create a whole artificial world for its protagonist is not (yet) possible, which caught the public's imagination, partly because of the sheer relevancy of the idea but also because of another element unusual in sci-fi, a performance of incredible warmth and vulnerability from Jim Carrey.

The conceit is pretty much summed up in a screaming voice-over at the beginning of the Tru Talk segment of the show itself. "One-point-seven-million were there for his birth... 220 countries tuned in for his first step... An entire human life recorded on an intricate network of hidden cameras broadcast live and unedited 24 hours a day, seven days a week to an audience around the world!" Truman himself is only aware that he lives in Seahaven, an impossibly sundrenched, pastel-dappled island town which, owing to a carefully implanted fear of water, Truman cannot leave. (In fact the screenplay originally had Truman in a Seven-style, grim rain-sodden city which Weir rejected, opting instead to shoot in a Florida retirement village.)

Starting quite literally with a falling star — a studio lamp marked Sirius 9 tumbles from the "sky" — Truman begins to suspect that he is at the centre of a conspiracy. His wife insists on shouting product endorsements at the most inopportune moments, an elevator has no back walls revealing what looks suspiciously like a caterings service table surrounded by bored extras. Finally making a run for reality Truman is nearly killed by show creator Cristof before opting for the real uncertainties of the world outside the TV studio instead of the his ersatz existence.

Newspaper headlines like "Who needs Europe?" rub shoulders with posters showing lightning striking planes ("It could happen to you!" reads the slogan) and hokey TV sitcoms which announce that "You don't have to leave home to discover what the world's all about" all conspiring to counteract Burbank's curiosity. There's also tremendous fun to be had reading interpretations onto the movie. There's the "Garden Of Eden in reverse" take in which Truman is Man fighting his way out of paradise, stopped by a terrified "creator". There's the anti-Capraesque angle, in which American smalltown life is not the very essence of perfection but stifling, repressive and false. There's even the fact that the whole premise is contained within its central character's moniker: the True Man's second name is Burbank, the LA suburb where the studios reside.

In Truman he creates a true hero for the times whose humanity shines even as he realises the extent to which he has been manipulated.

It's easy to poke holes in the film. The show itself would in reality be deadly dull. The audience is as complicit in Truman's plight as Cristof, yet they are presented sympathetically. And why does Cristof attempt to make Truman stay once he has rumbled the game? But then, The Truman Show is best seen as a modern day fable (and no-one nit-picks the Hare And The Tortoise). It's a cautionary tale about the invasive, corrupting nature of a society that believes it has the right to watch everything. And it's a point that gets more, not less, prescient as we edge into the second millennium. With real life shows like Castaway 2000 and Big Brother defining millennial TV and communications technology advancing with increasing rapidity, a real Truman Show becomes ever more likely. The events of Terry Gilliam's Brazil famously take place 20 minutes into the future. The Truman Show may be a lot closer than that.