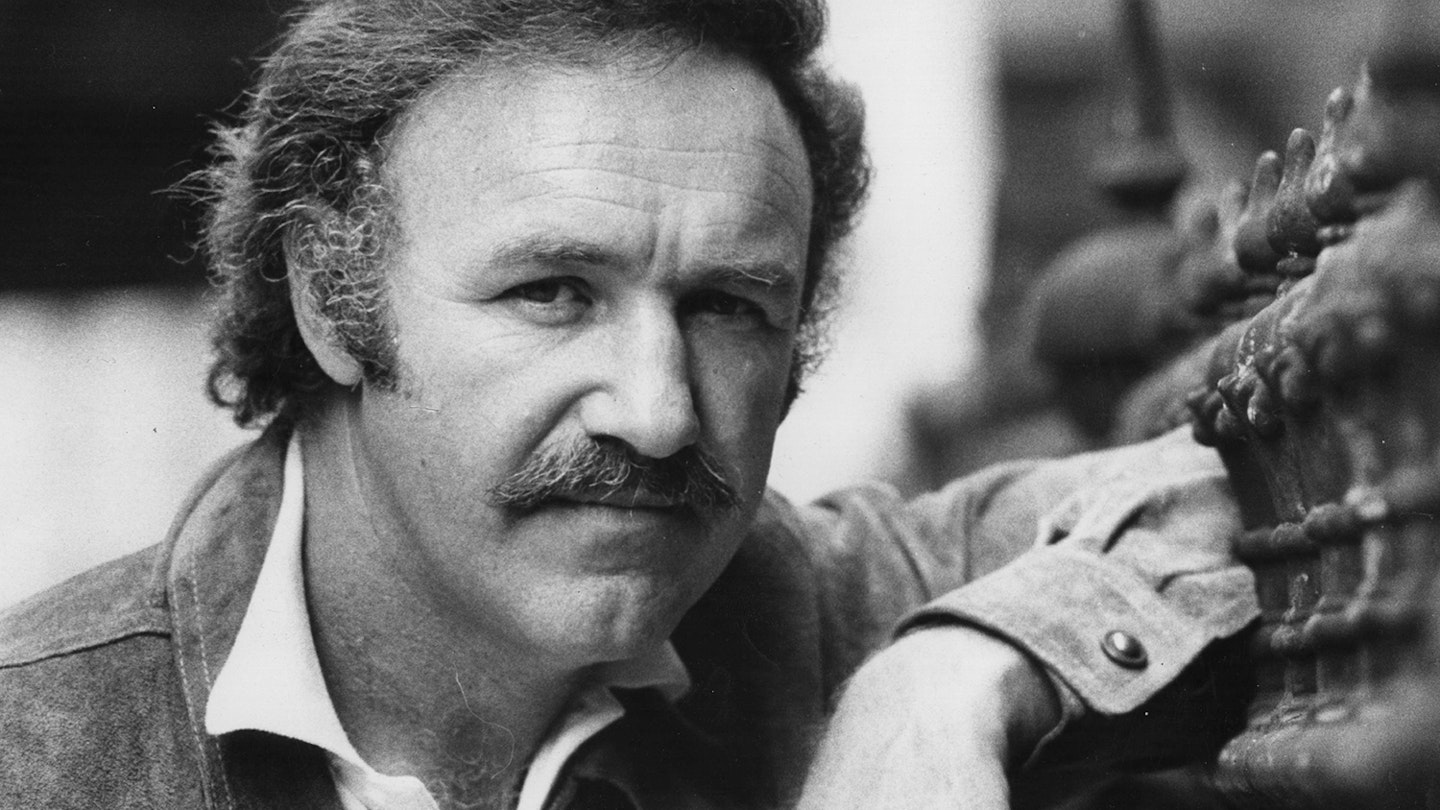

Almost 30 years before the Florida recount decided the US presidential race, another close-run contest between two equally popular men ended in a similar re-examination of ballot papers. The Best Actor trophy at the 1972 New York Film Critics awards was a tie between Gene Hackman for The French Connection and Peter Finch for Sunday Bloody Sunday (1971). They conducted a recount, and Hackman clinched it. The best man won.

The role of hardball New York cop Jimmy "Popeye" Doyle made Gene Hackman. With typical good grace, he plays down his part in the film's success: "I really don't think I had anything to do with the quality of the film. That was a director's film. Anybody would have been good in my role."

He's wrong, of course, though The French Connection might be described as a director's film. When producer Philip D'Antoni put forward 31 year-old William Friedkin for the job, 20th Century Fox swallowed hard. Friedkin had only The Night They Raided Minsky's (1968) and The Boys In The Band (1970) to recommend him, but D'Antoni (who'd previously produced Bullitt (1968) with the equally untried Peter Yates) fancied him for being an unconventional choice. This was not intended as a standard cops-and-robbers flick.

The book, by Green Berets author Robin Moore, was written like a fictional potboiler but based on fact: the story of a 1962 heroin bust in New York, in which detective Eddie "Popeye" Egan (his name was tweaked for the film) and his partner Salvatore Grosso (Buddy Russo on screen) led the swoop on $32 million's worth of incoming brown stuff from Marseilles. For a true story — the book even has maps! —it read like a cracking movie. But all credit to creator of Shaft (1971), Ernest Tidyman for an imaginative job on the screenplay b which he won an Oscar), ding in the memorable establishing sequence in which Popeye and Russo (Scheider) go undercover in a biting New York winter as Father Christmas and pretzel vendor. They chase and interrogate a vendor of less legal wares, and Popeye taunts him with his now-legendary riddle, "Do you pick your feet in Poughkeepsie?" (Hackman was so offended at having to retake this violent assault 27 times, he threatened to walk away from the picture, but was dissuaded by the threat of legal action.)

The French Connection is a deftly-mixed cocktail of realism and dramatic licence, encapsulated in the blending of Moore's reportage and Tidyman's streetwise invention (as in the bit where a hip chemist tests the French importers' heroin for purity and describes it as "junk of the month club"). Friedkin's hand-held documentary style was the perfect vehicle for the film's pumped-up verite: it's since become Hollywood shorthand for "gritty realism" to shoot long and let the camera wobble, but in 1971 this was really radical stuff for a mainstream studio film.

However, for all the sleazy authenticity (much of the action was shot in real-life junkie hotspots in Manhattan and Brooklyn, and Hackman went on patrol with Eddie Egan to research the unconventional ways of the Narcotics Bureau), the high point of The French Connection remains its car chase, a sequence that was added to Tidyman's screenplay when no studio would touch the script. Its inclusion was a bare-faced commercial decision, no doubt inspired by Bullitt's own four-wheeled money shot. It's testament to Friedkin's commitment (and that of stunt driver Bill Hickman) that the car chase trashed all before it and has yet to be matched for visceral, brake-squealing energy.

The sequence is actually a train chase, as Doyle's Pontiac sedan pursues an elevated subway carriage containing French smuggler Nicoli (Marcel Bozzufi, star of the film's poster image). Wreaking controlled mayhem for weeks of shooting under the Stillwell Avenue Line was not enough realism for Friedkin; he wanted an uninterrupted shot of the entire chase with one camera on the bumper and one inside the car to capture Popeye's point of view. Hickman took the wheel and drove 26 blocks with a flashing light to alert the very real pedestrians and drivers. See that woman with a pram? Real woman. Real pram. Real baby.

Maverick cops are ten a penny in the cinema, as are their trusty sidekicks but there is something about the way Hackman plays Popeye that elevates him above the herd. When he first read the script he saw his chance to emulate Cagney, but he's far more than a screen-filling tough guy — he exhibits the same insouciant, grinning authority that Hackman managed to subtly invest in characters as diverse as The Poseidon Adventure's Rev Scott and Crimson Tide's Captain Ramsey, over 20 years apart. Popeye Doyle is Gene Hackman finding his own brand.

Maybe The French Connection is an actor's film after all.