Steven Spielberg has made a number of masterpieces: Jaws, Schindler, Raiders, and E.T. spring readily to mind. He has, though, never made a more complete film than Close Encounters.

Released in the same year as Star Wars, in many ways it did more to enhance the genre, and in the landing of the mothership produced one of the great moments of cinema history. Originally titled Watch The Skies, the source material was Dr. J. Allen Hynek's The UFO Experience: A Scientific Enquiry (he was the first to establish the three stages of close encounter) and hints of The Day The Earth Stood Still. And while the likes of Paul Schrader and Matthew Robbins worked on various drafts and conceptual ideas, the screenplay is credited solely to Spielberg and to all intents it reflects his vision entirely.

Spielberg has never made a more complete film than Close Encounters.

Although E.T. ranks high, Close Encounters is Spielberg's most personal film. Its inspiration harks back to watching a meteor shower as a sci-fi obsessed young boy in Phoenix and his 1964 home movie, the alien-themed Firelight, was undoubtedly the precursor. The director himself later described this film as encapsulating, "My vision, my hope and philosophy".

It was an arduous shoot. They had six rap parties since endings were constantly revised when the director was inspired to go back and expand his vision (he kept watching The Searchers throughout the shoot, which did and didn't help). Overbudget and way overschedule, he completely missed his release date, allowing buddy George Lucas to get ahead of him in the change-movies-forever stakes with Star Wars. It was worth the trauma though.

The film that forever sealed Spielberg's reputation as one of cinema's great directors.

Every detail of Spielberg's vaunting ambition is reflected in the finished product. Typical of Spielberg (and, indeed, redolent of his heroes Hitchcock and Capra) this is a film that focuses on average people: the extraordinary occurring within the heart of the ordinary. Roy Neary (Dreyfuss) is an electrical engineer touched by the hand of God (well, shiny happy people from deep space) thrusting him onto to a spiritual quest that tugs beneath reason and delivers him finally to the iconic shape of Devil's Tower, Wyoming. Alongside his journey is that of Francois Truffaut as Claude Lacombe (based on famed French UFO expert Jacques Valle), the scientific team leader whose more pragmatic investigations lead him eventually to the same place — but without the interplanetary spiritual connection ("I envy you," he whispers to Neary, when he is preparing to embark on the ultimate encounter).

Also drawn to Devil's Tower is Jillian Guliar (Melinda Dillon) who is seeking the return of her kidnapped child Barry (Guffey). On a fundamental level this is a film about faith, the need to "believe". As with most Spielberg films, the message is powerfully and anti-cynical. Innocence and optimism prevail — the aliens are angelic, childlike, non-threatening. And it is the innocence, Neary's inner child, that the alien beings finally choose (just as they would have chosen Spielberg himself). This is a film without bad guys, the drama constructed out of yearning and mystery not peril.

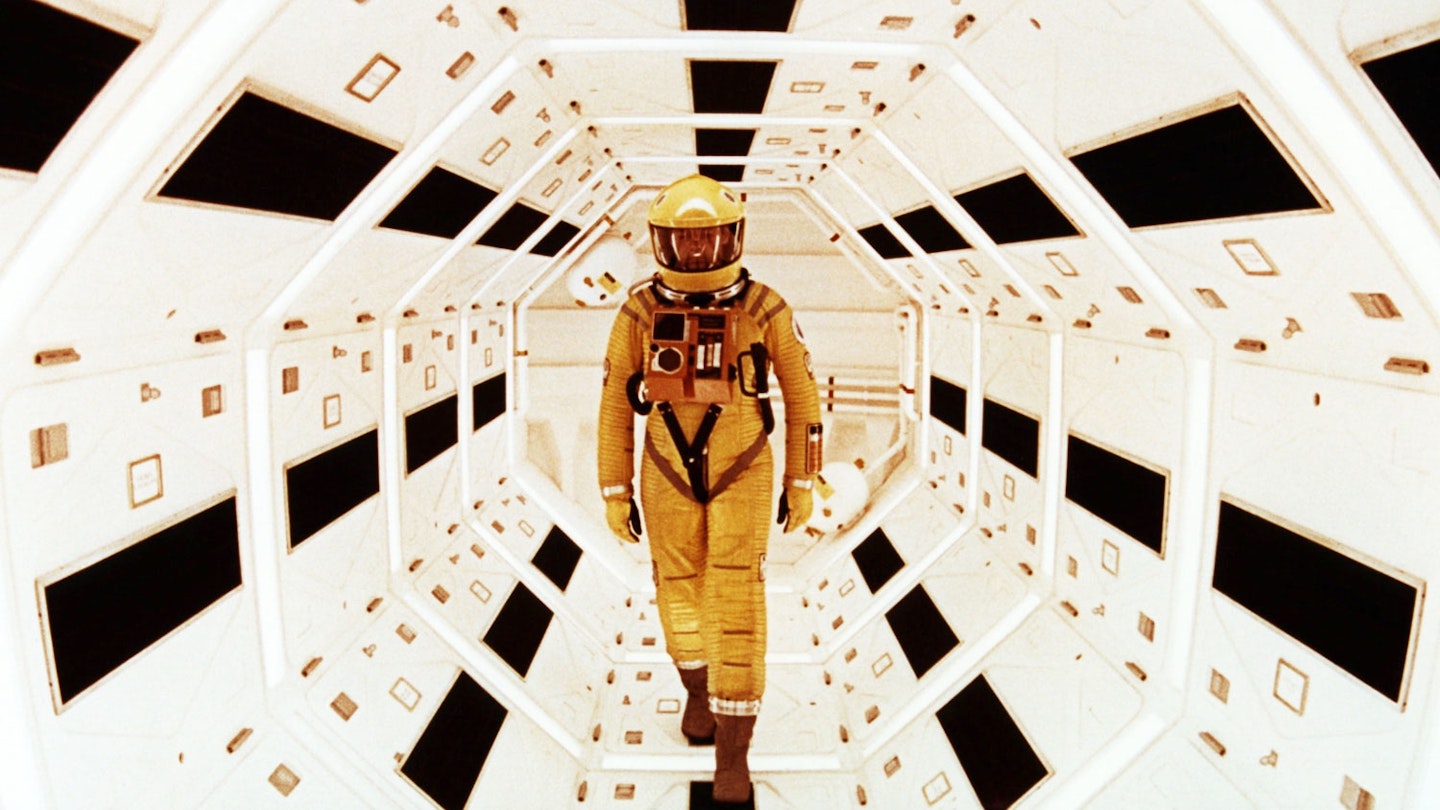

And no account of Close Encounters can pass by without mention of that staggering finale — the arrival of the mothership. In these days of CGI, there remains a holy aura around this sequence. Douglas Trumball (who did all the trippy stuff for 2001) created something that tested the boundaries of both the cinema screen and the audience capacity for wonder as the city-sized craft is lowered into the frame and locks itself somewhere deep within the memory.

As with most Spielberg films, the message is powerfully and anti-cynical.

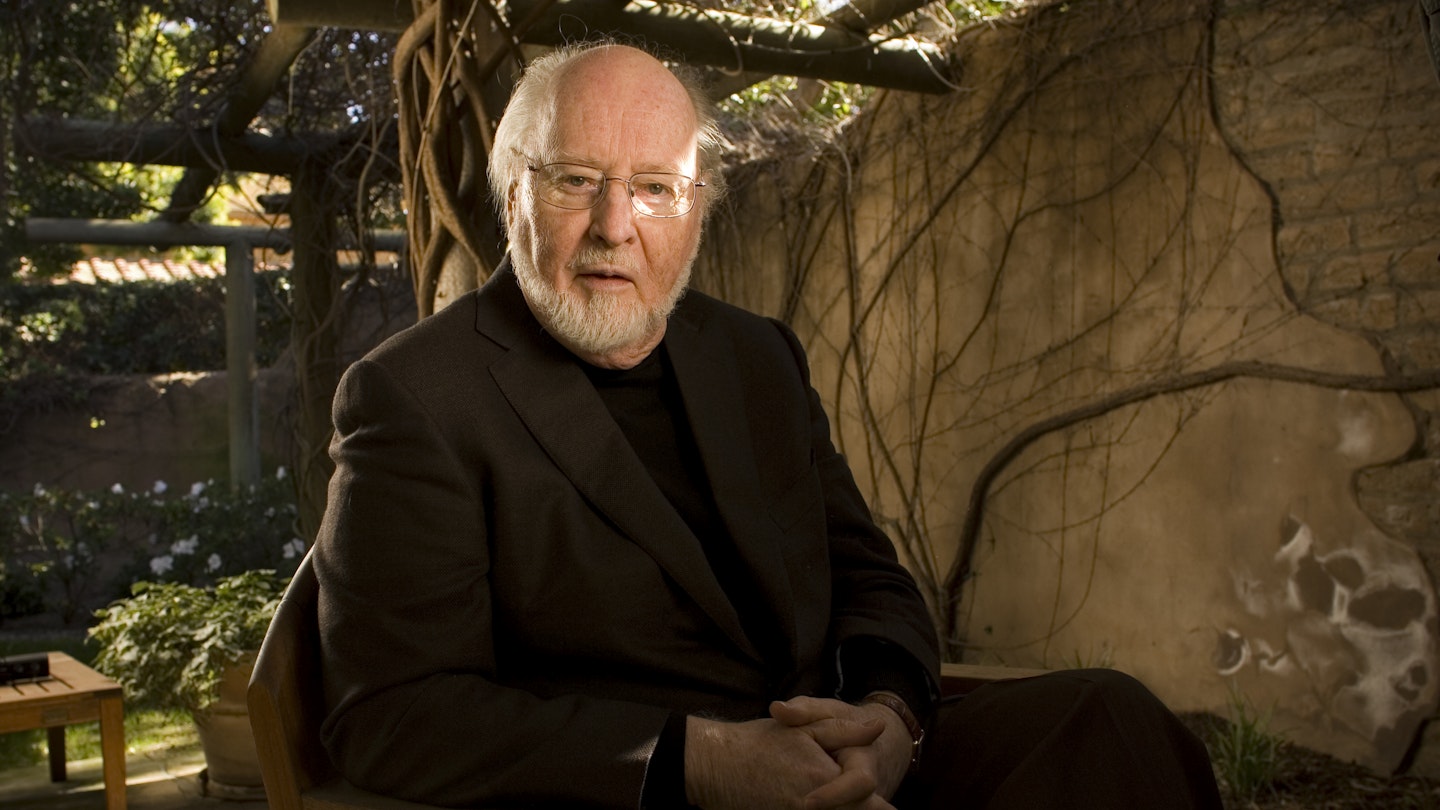

There are other notations to chalk up. The debate between the two versions — Spielberg laid on a special edition in 1980, although its interior shots of the mother ship added little to the mood of the original. It is the first Spielberg film to truly encompass his preoccupations: children, family, suburbia, and the emotionally abandoned. And then there is the music: the chord progression that John Williams masterfully inserted as the theme to universal communication.

Decades on and the approach to alien visitation has come full circle. The X-Files, Independence Day and numerous aggressive additions to contact philosophy have returned to the paranoid notions of yore, where conspiracy and threat are the abiding themes. Here, in the film that forever sealed Spielberg's reputation as one of cinema's great directors, dwells something else entirely: a sense of wonder, that the unknown can reveal joy, and — akin to the overarching hope of Schindler' List — that humanity may actually have a chance of succeeding.