For his sixth movie as writer-director, Cameron Crowe returns, with clear determination, to the well that has fed his most distinctive work. Elizabethtown is mottled with all the hallmarks we have come to expect from Crowe, and if some of them are stamped with a heavier hand than usual, that hardly detracts from its affecting charm.

In the wake of Vanilla Sky, an uncharacteristic rush of adrenal psychedelia that baffled and infuriated much of his following, fans will be comforted to find Crowe back on familiar ground - deeply felt human drama with effortless overtones of wistful comedy.Elizabethtown does not have the sharply barbed narrative hook of Jerry Maguire or the engrossing backdrop of Almost Famous; it lulls you into a gentle embrace rather than grabbing you with a situational come-on.

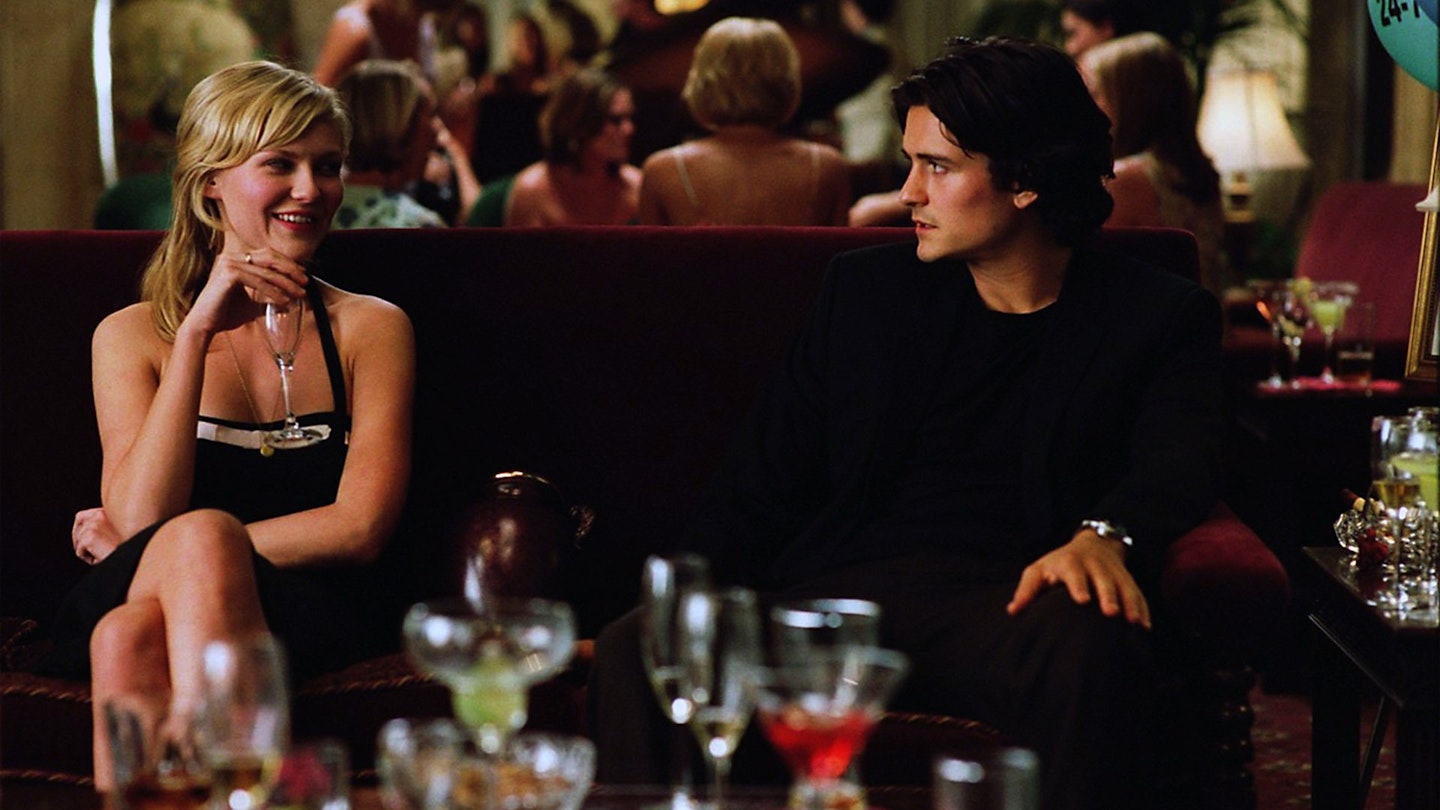

Shorn of conceptual set-dressing and with a streamlined, propulsive plotline, Elizabethtown unravels in unaided accord with character arc and the emotionalinterplay of its major protagonists.Front and centre is Bloom's Drew Baylor, a part that requires our Orly to prove his acting mettle without the get-up and funny wigs. Cast as a put-upon everyman by Billy Wilder's biggest fan, Bloom turns in a decent Jack Lemmon (complete with American accent) in what is surely his best performance to date.Bloom is ably abetted by Kirsten Dunst, who is at her most edible as the incorrigibly meddlesome yet irresistible flight attendant.

As Claire and Drew's romance duly blossoms, the absent son is inevitably seduced by the mildly eccentric residents of Elizabethtown - who, he discovers to his amazement, harbour an unswerving possessive affection for his father - all of whom, down to the lowliest bit parts, are drawn with Crowe's keen eye for human foibles.Conspicuously absent, however, is the lurking edge of darkness that underscores the bittersweet euphoria of his most satisfying films - the fraught, borderline abusive relationships at the heart of Say Anything, Jerry Maguire and Almost Famous, for instance - and there are excursions into sentimentality that strike one, on first viewing at least, as unnecessarily protracted, even for a filmmaker who has shown an uncertain grip on the syrup spoon before ("You complete me" etc).

Still, real people have a great capacity for sentimentality, especially when their lives are clarified by grief, and it is to Crowe's credit that he refuses to shy away from that. In fact, it is exactly this sloppy fallibility to the proverbial slings and arrows that Elizabethtown celebrates, just as it does the unbreakable bonds of family and the redemptive power of love. And there is no better interpreter of these sticky, delicate, inconvenient facets of our existence than Crowe, certainly not one working in the Hollywood mainstream at any rate, and that includes his mentor, James L Brooks.

This is also Crowe's most personal film by far. His own father died 16 years ago and absent fathers have been a recurring feature, if not a theme, of his movies ever since. Elizabethtown is the result of a recent visit to his father's birthplace in Kentucky, somewhere he had not visited since the funeral, and the flood of emotion that overtook him. Armed with that knowledge it is easy to forgive Elizabethtown both its mushy longueurs and the moments where Crowe signs his signature with a paintbrush rather than a quill.