It's increasingly difficult now to convey the excitement of a film being shown on television. There was a time — pre-Sky, pre-digital, pre-DVD even — when you were at the mercy of the programmers' whim. Hell, there were only three channels and they were off half the time. In light of this, respect is due to the BBC for what must be one of the great innovations in the history of television. No, we're not talking ground-breaking, thought-provoking documentaries, or even Big Brother. What the Beeb did, in the halcyon days of the 70s, was to turn their weekend late-night slot into a horror movie double bill. Thus it was possible to see Karloff's Frankenstein, followed by Christopher Lee's take on the same role. The next week it might be Bela Lugosi's Dracula and, in sharp contrast, Christopher Lee, in the 1958 version. It was Universal versus Hammer and at the time, that colour stuff sure looked good.

"Hammer" is now a word synonymous with the history of horror movies. Hammer Films, the films that fuelled the fantasies and nightmares of several generations, began as a distribution outfit in the 1930s. William Hinds — the "Hammer" of vaudeville act Hammer & Smith — lent his name to the company, although it was initially Enrique Carerras, and later his son James, who ran the operation at Bray Studios. They made a variety of movies (including cinematic spin-offs from the popular Dick Barton radio show) hitting on the perfect formula in the mid 50s. The Quatermass Experiment, based on the BBC TV serial, showed Hammer that audiences craved horror.

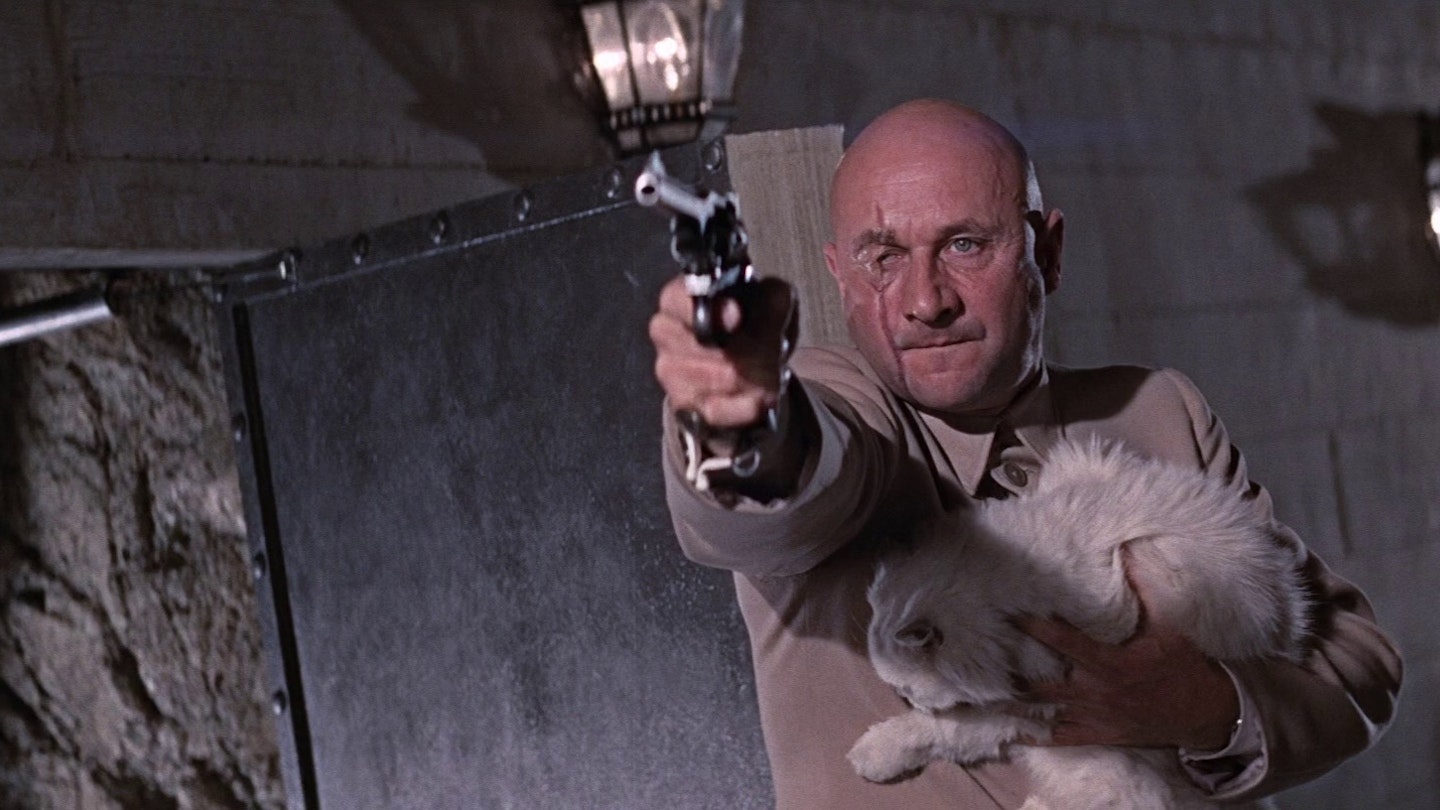

What Hammer did — and this shouldn't be under-estimated — was bring colour to the horror genre. Even two years later in Psycho, Alfred Hitchcock was using chocolate syrup to simulate blood in the shower because it looked better in black and white. But when Christopher Lee sucked neck in Dracula, you saw the lush delights of Eastmancolor etched indelibly on his teeth. Casting, of course, played a huge part in the success of the Hammer cannon. Having cast Peter Gushing as the icy Baron in the previous year's Curse Of Frankenstein, they remoulded him as the urbane man with a conscience — Van Helsing, the vampire hunter, a role later tackled, to lesser effect, by the likes of Laurence Olivier and Anthony Hopkins. But the real casting coup was Christopher Lee. Previously seen opposite Gushing as the Monster in Curse Of, Lee was here allowed to display his haunting looks, imperious manner and blood sucking-charm.

In the hands of writer Jimmy Sangster and director Terence Fisher, however, this incarnation of the Count deviated sharply from Stoker's original almost from the outset. Johnathan Harker (John Van Eyssen) travels to the Count's castle — a fine example of production designer Bernard Robinson's distinctive style — not to work on his books, but as an agent of Van Helsing, who is intent on destroying him. Similarly, Lee's majestic interpretation of the undead owed little to Bela Lugosi's performance. He opted instead to play Dracula as a cool, debonair aristocrat, whose charm adds to the sexual undercurrents and inherent eroticism of the vampire myth, something that director Fisher was eager to explore (and something that would become a mainstay of the increasingly sexed-up Hammer output).

Gushing returned as Van Helsing in 1960's Brides Of Dracula, but Lee didn't don the fangs again until 1965's Dracula: Prince Of Darkness. He played the role for Hammer a further five times, well into the 70s, (taking a break briefly to play the role in Italy for Jess Franco's El Conde Dracula (1970)), but no subsequent outings matched the sheer visceral delight of this original.

When Tim Burton decided to make 1999's Sleepy Hollow in the guise of the great British horror movies, he clearly showed how well he understood the impact of Terence Fisher's direction, James Bernard's magnificently excessive scores and the fact that if the gore looks like jam — it doesn't matter. Just feel the beautiful melodrama.