Any new Quentin Tarantino release is an event. Like his latest protagonist, Tarantino is a filmmaker Unchained (although, to be fair, he was never really Chained to begin with). He has never exhibited any agenda beyond revelling in a seemingly boundless love of cult cinema and sharing that with an audience whom he never patronises by assuming they know less than he does. So, for good (Reservoir Dogs, Pulp Fiction, Jackie Brown, Kill Bill, Inglourious Basterds) or ill (Four Rooms, Death Proof), his movies, however wide their scope, always come unhampered by studio fussiness and unvarnished by new trends: digital, CGI, 3D — IMAX, even. For a man credited with tearing up the rulebook, he is staunchly traditional.

And to see him tackle that most traditional of American cinematic genres, the Western, makes Django Unchained a double-event. The importance of the Western, so rich with mythic power, to America’s very sense of itself is not to be underestimated. Inglourious Basterds was a riot, outrageously rewriting the history of the Second World War to the tune of its own filmic re-presentation during Tarantino’s formative years. But Django Unchained digs deeper, into even more thematically fecund soil.

Just as it was a thrill for late ’60s counterculture kids to see it ploughed into Spaghetti by European maestro Sergio Leone and those who followed (not least that other Sergio, Corbucci, director of the original Django), there has been understandable anticipation for QT’s own spin.

Yet, strictly speaking, Django Unchained isn’t a Western. Tarantino himself has said, if anything, it should be tagged a ‘Southern’. Its events predate the Civil War by a few years, whereas most Westerns squat between that devastating conflict’s conclusion and the dawn of the 20th century. (When, not coincidentally, cinema itself was born.) They also occur far from the rugged frontier of American myth, with half the movie pinned to a single Mississippi plantation — a locale of faux-aristocratic if sinister elegance, rather than the slop and dust of the prairie cattle-trail or timber-clad frontier camps. Tin star-sporting sheriffs do feature, but are given almost comedically short shrift. Native Americans and border- bothering banditos are notably absent.

So, ‘Southern’ it is. Or rather, ‘Spaghetti Southern’. For, while Tarantino has skirted the Western’s customary historic home, he has still embraced the style of the two Sergios and their contemporary emulators, from the operatic grandeur of the score (Ennio Morricone composed a piece for Django Unchained) to the oozy, lurid scarlet fountains that cascade gorily with every gunfight.

It is also, interestingly, very much a fairy tale; more so, in fact, than myth. For the first time, Tarantino plays it linear (although there are degraded-stock flashbacks) and portrays a single character’s journey. There are no shifts in perspective, no chopping up of the chronology, no chapter separations. It is, essentially, a straightforward ‘rescue the princess’ quest, heightened by being located amid the Old World-pining feudal system of the Southern aristocracy.

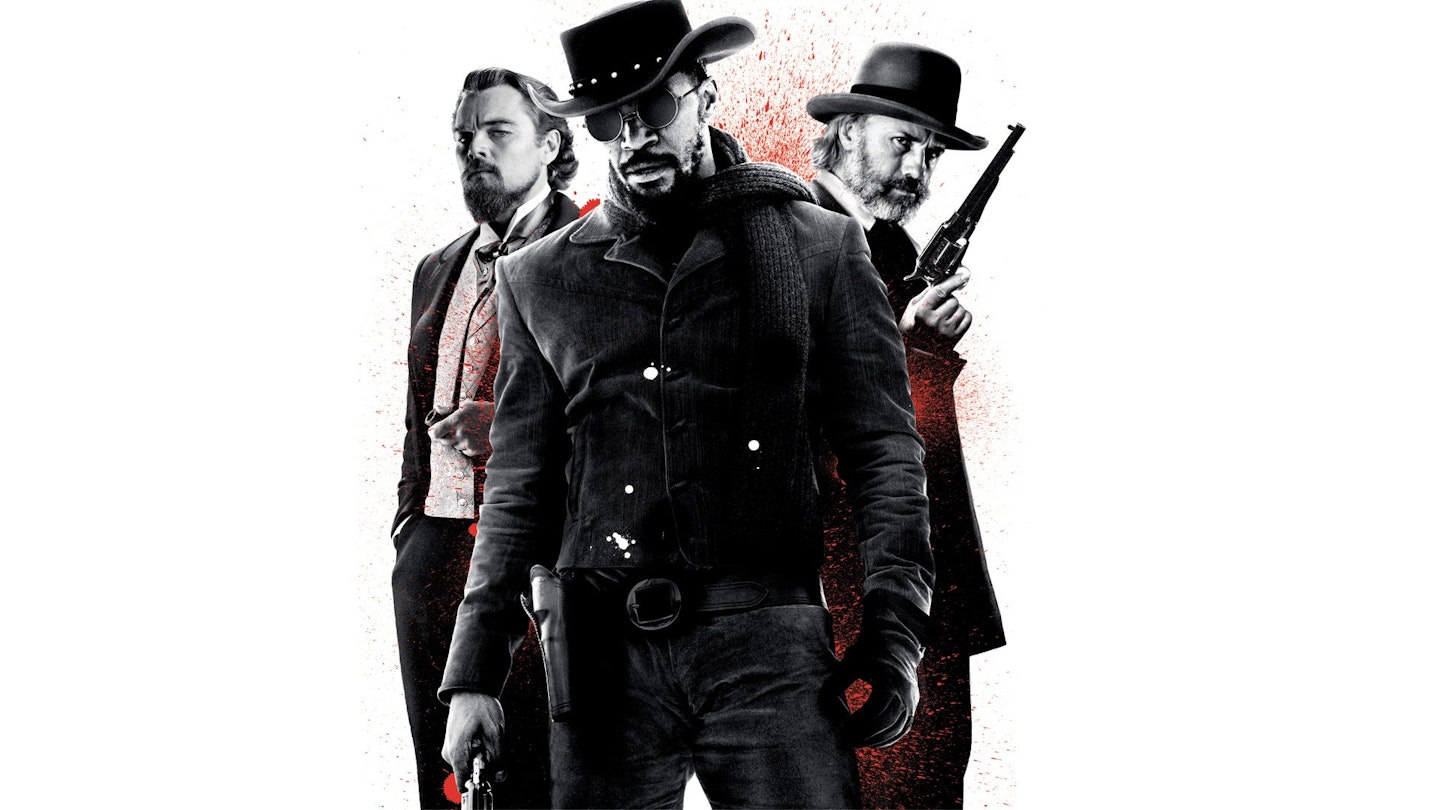

The script even spells it out. Having relieved laconic slave Django (Jamie Foxx) of his irons, German bounty hunter Dr. King Schultz (a hirsute, dapper Christoph Waltz) is astonished to learn that, not only is his new partner married, but also his wife (Kerry Washington) is named Broomhilda von Shaft. Over a campfire, he tells Django of her namesake, Broomhilda of German legend: how she is abducted by a dragon and taken to the top of a mountain where she is surrounded by hellfire. It is then up to hero Siegfried, explains King, to make the perilous journey to rescue her. And Django, he says, is “a real, live Siegfried”. Thus Django has his own hellfire to contend with, and there is a dragon to battle.

Speaking of which, one of Django Unchained’s most exquisite pleasures is Leonardo DiCaprio’s Calvin Candie, the owner of grand plantation Candie Land. Although he does not breathe fire so much as hot air. When considering DiCaprio for the role, Tarantino reimagined Candie as a “petulant boy emperor”. It is a role the actor plays to hateful perfection: a spiteful, brown-toothed bully, avaricious, vain and prone to flattery, whose sometimes unctuous civility is merely froth bobbing atop dark, poisonous waters. There is always the sharp threat of violence when he is on screen, something Tarantino hones during a dinner-table sequence which comes close to matching the German-bar scene in Inglourious Basterds.

DiCaprio forms a superbly nefarious double act with Samuel L. Jackson as Stephen, the head house-slave: white-haired and rickety, eye-bulgingly apoplectic at the sight of Django on horseback, disgusted at the idea of a “nigger” being allowed to stay “in the big house”. And Waltz is also excellent, as accomplished playing a hero for Tarantino as he was as the villainous Hans Landa in Basterds — despite residing at the opposite end of the moral spectrum, Dr. King is just as brilliantly verbose.

Sadly, the weak link (ironically) is Jamie Foxx. The man has physical presence, that is undeniable, and as Django he certainly looks the part. Yet he never feels entirely right as the gritty, gunslinging hero — or rather, sounds right. Foxx is gifted with a lilty, soft, musical voice, but it jars against Django’s terse deliveries. “I like the way you die, boy,” should be a grit-spat humdinger of a zinger. But with Foxx it falls like a feather.

There are other problems, too. Tarantino’s penchant for black comedy and hyperreal, sometimes cartoonish violence runs up against his bold decision to depict the horrors of slavery head on: the lashings, the terror of the “hot box” and, in one bone-chillingly nasty scene, the pugilistic atrocity of a Mandingo fight. This, of course, is all part of Django’s story, and utterly relevant. But it doesn’t sit comfortably next to those more ‘Tarantino’ elements or his brand of Spaghettification.

Django Unchained is also, frankly, just too damn long. Or rather, its story is just too damn short for the running time (which pushes three hours). There is nothing inherently bad about long running times, and one of Tarantino’s strengths is the way he’s unafraid to let a scene run and run, his reams of dialogue unfurling in luxuriously unhurried fashion. But that tendency is here at its least tempered. Django could easily have moved faster without at all harming the quality. It could have taken even more of a lead from its Italian-Western inspirations and more often cut to the chase, and the action. To quote Tuco in Leone’s The Good, The Bad And The Ugly: “When you have to shoot, shoot. Don’t talk.”