When cinema succumbs to illness and disability, we tend to be offered either a disease-of-the-week tearjerker or a high-minded bid for Oscar glory. Rarely does a film offer proof that personal tragedies really can inspire. The Sea Inside was one; The Diving Bell And The Butterfly is another.

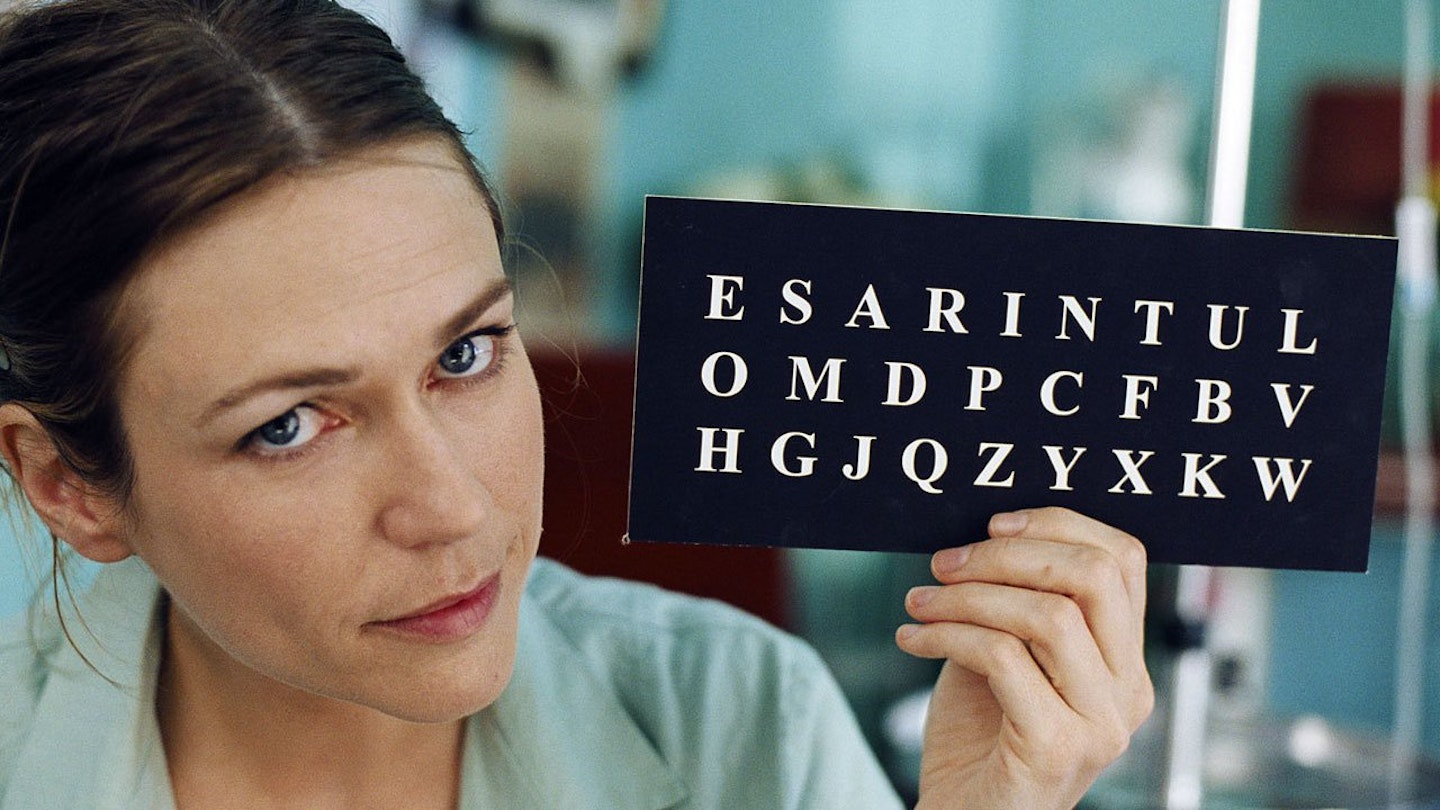

In December 1995, a stroke left Elle editor Jean-Dominique Bauby (Mathieu Amalric) unable to move anything other than his left eyelid. With an effort of willpower that is almost impossible to imagine, Bauby collaborated with book editor Claude Mendibil (Anne Consigny) on a memoir, dictating pages blink by blink. There was no miracle cure for Bauby, who died two days after his book was published. The miracle is that such a wonderfully wry description of Bauby’s inner world could be translated to the printed page.

Equally extraordinary is how Bauby’s story has reached the screen. Director Julian Schnabel shoots much of the film as if through the left eye of the bed-ridden Bauby. We share the restrictions of his mobility and the frustration this brings. We hear, through voiceover, the words that exist in Bauby’s mind but never pass through his lips.

Occasionally Schnabel offers us external shots of Bauby in his wheelchair with his family and friends. More effective, however, are memory sequences of a fully-fit Bauby shaving his housebound father (Max von Sydow) or visiting Lourdes with an ex-girlfriend. It is a brave but not intimidating approach. Indeed, the visual style itself becomes the key element that allows us to understand and admire the way that Bauby’s mental vivacity (the ‘butterfly’) overcomes his physical limitations (the ‘diving bell’).