The fate of Quentin Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez’s Grindhouse project was calamitous for several reasons. Not only did The Weinstein Company take a bruising at the box office, but a dangerous precedent was set: Grindhouse was deemed a flop on the basis of its opening weekend. But it remains one of the best reviewed films of the year — even within the Empire office, where hairs are split with laser-guided pedantry, the full three-hour, double-bill experience won over everyone who saw it.

At that point we still believed the UK would get the full capital-G combo, but soon it was revealed that we would get QT’s serial-killer flick Death Proof first, with RR’s zombie-movie homage Planet Terror to follow. So Grindhouse now faces a new, inverse problem. In the US, the audience wasn’t into the concept of a retro ’70s theme, but in the UK, everyone knew exactly what it would be — and then they didn’t. What about the missing reels, the fake trailers? And would it be the adrenaline rush we were promised?

The good news is that the first individual film does not sacrifice the ethos of the double-bill. Instead, Death Proof emerges under the grindhouse banner — note the lower-case g — with most of the portmanteau film’s values intact. From the opening credits it evokes the sticky spirit of pre-multiplex movie houses, starting with the crackling ‘Our Feature Presentation’ intro. Even the title card, with its defiantly retro typeface, gets it right.

Tarantino plays with genre convention, beginning with the roar of an engine much like Monte Hellman’s 1971 road movie Two-Lane Blacktop, and opening on a pair of female feet on a dashboard before the film’s fake ‘original’ title — Quentin Tarantino’s Thunder Bolt — flashes briefly on the screen. The mash-up of references is deliberate and rewarding: Death Proof is so many things, in the way ’70s American cinema often used

to be. It’s southern Gothic, it’s a chicksploitation movie, it’s a psycho movie.

These things were in evidence in the Grindhouse cut, but what becomes clear from the full version is how much Tarantino riffs on them — although the film is not defined by its elements. For a slasher film, it spends a lot of time with its victims. For a hot-chick movie, there’s no nudity. And for a psycho movie, it sends up the whole post-Silence Of The Lambs criminal romance with a brilliantly subversive twist.

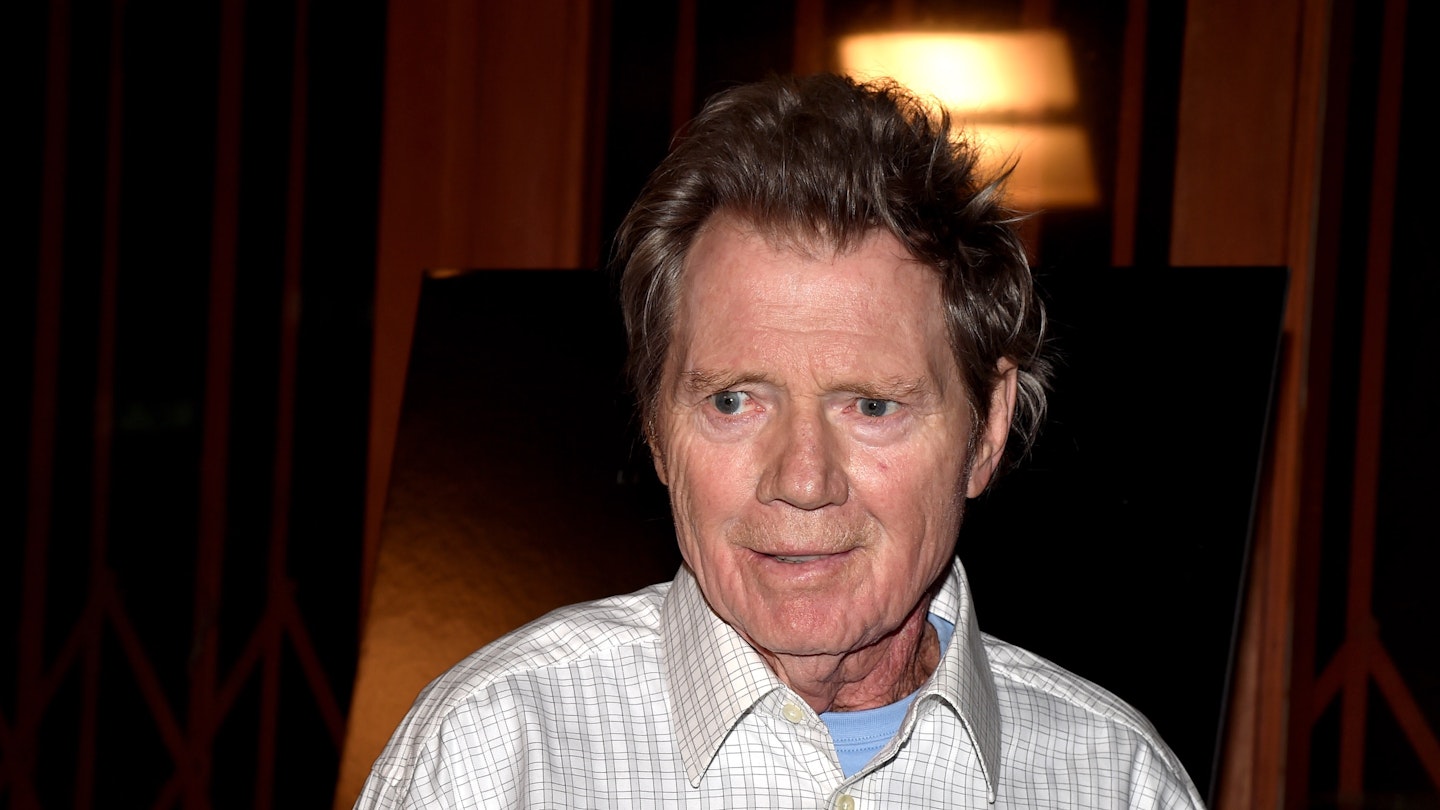

And, instead of feeling like half a bigger movie, Death Proof seems like two more. The first half, shot in the boozy, neon nighttime of Austin, Texas, has a sleazy charm that only really becomes explicitly sexual in Vanessa Ferlito’s white-hotpants lap dance (part of Grindhouse’s ‘missing reel’). And after the murder scene — a raw, visceral pile-up that leaves nothing to the imagination — the second half is a stark chase movie somewhere between Convoy and Duel, based on ’70s movies so regional that most barely graced the UK circuit even then. In the first half, Stuntman Mike — a terrific Kurt Russell — is a man out of time who wreaks terrible revenge on the women he despises. In the second, time runs out on him, and the boogeyman is well and truly boogied.

If this sounds like typical Tarantino, however, it isn’t. Forget the sleek pop-culture cool of Pulp Fiction and Kill Bill; Death Proof

is a sister-piece to Jackie Brown, defiantly old-school and striving for a less showy authenticity. That QT left most of this talky stuff in the supposedly “cut past the bone” Grindhouse version was a source of controversy, but in the longer cut these scenes have a definite flow. Yes, in the last stretch, dialogue fatigue starts to creep in, but then Tarantino switches to action mode, building to a white-knuckle cat-and-mouse chase that barnstorms to a climax.

By this time, the ‘extras’ — the scratches, glitches, black-and-white reel thing — are down to a minimum and Tarantino accelerates with a bravura car chase that gives Tracie Thoms and Zoe Bell the most badass fun a woman could ever have.

It won’t please everybody, but Death Proof is a berserk and memorable thrill ride that, like Stuntman Mike, is way, way smarter than it looks and, like the original Grindhouse, should be approached with an open mind and respect for its values, not its cost.