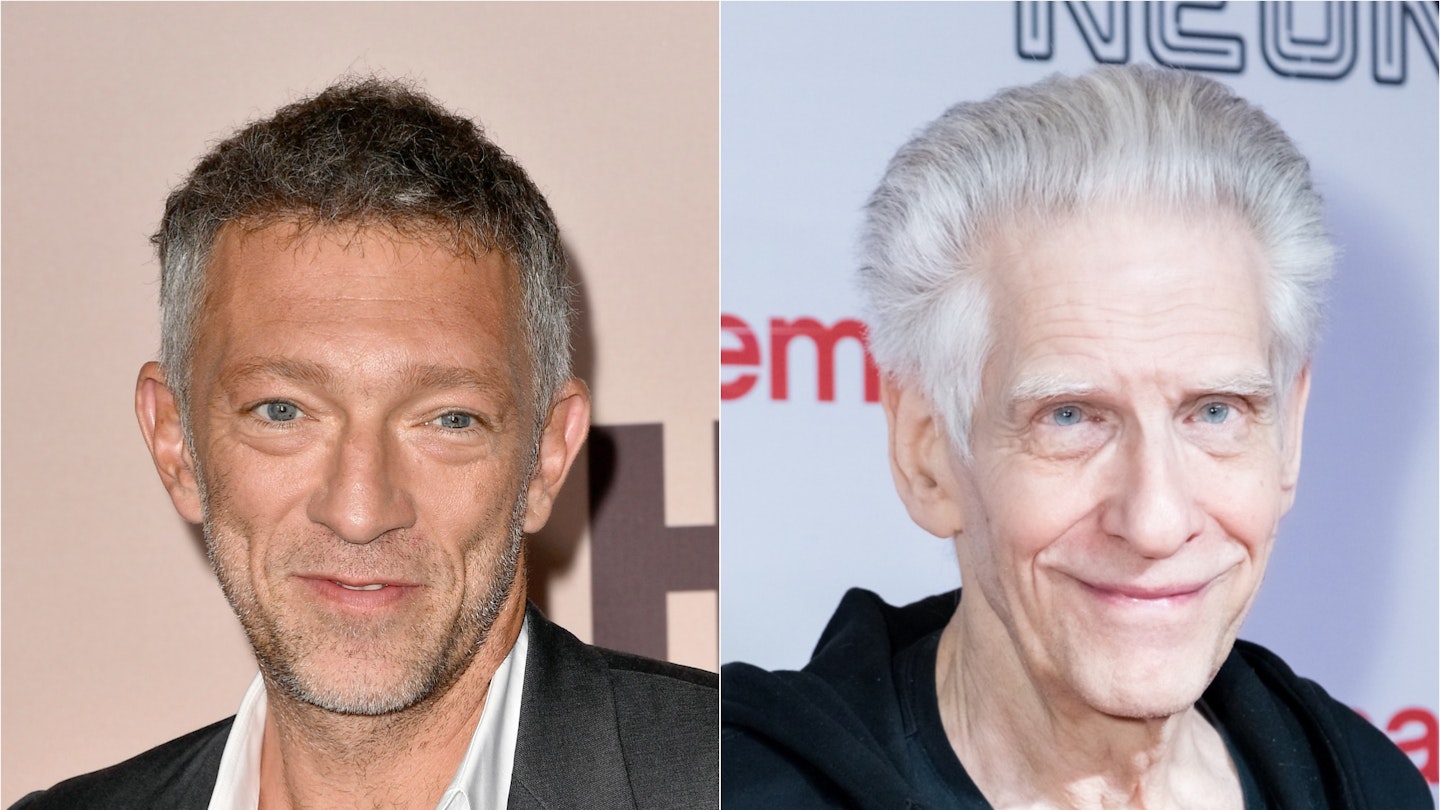

In May, when it played at Cannes, Crimes Of The Future was met with a quivering river of walk-outs, but also a six-minute standing ovation. Even in the fickle hysteria of Cannes, it was obvious David Cronenberg’s latest would prove divisive. With its slurpy autopsies and opulent wound-licking, this is not a film to watch munching a hotdog, or God forbid a burrito, but what did those Cannes walk-outers expect? Objecting to Cronenberg being transgressive is like complaining Michael Bay films have too many explodo-booms. Provocative is what he does.

This, his first horror since 1999’s eXistenZ, is being hailed as a comeback of sorts, but he never really washed his hands of the genre. His first novel, Consumed, was published in 2014 and slithered with cannibals and flesh-nesting insects. And besides, Crimes Of The Future was originally scheduled for a 2006 release, then titled ‘Painkiller’ and starring Ralph Fiennes. Which begs the question: what prompted Cronenberg to revive it?

Crimes Of The Future is a movie with a lot on its mind. Cronenberg is 79 now and the film raises questions, not only about mortality, but the future of mankind itself. From Scanners’ mutant psychics to The Fly’s metamorphosis, evolution is the pumping heart of Cronenberg’s body horrors. In Crimes Of The Future, he takes the concept to new nihilistic extremes. Set in a decrepit, polluted techno-future, humans have evolved into an unfeeling, pain-free species, immune to trauma and disease. The exception appears to be Viggo Mortensen’s performance artist Saul Tenser: a living, coughing factory of functionless body organs whose tumours are tattooed and extracted by his partner (Léa Seydoux) for an audience of horny voyeurs. Only Cronenberg could make something so shocking appear decadently perverse: the live autopsies are styled like the orgy in Eyes Wide Shut crossed with a Toby Carvery, and feel both alien and weirdly familiar. It’s the same insurgent erotica of Rabid, Dead Ringers and Crash.

Those scenes are the first of many nostalgic call-backs to the director’s past horrors. Videodrome’s analogue TVs get a cameo; Tenser’s bug-like ‘OrchidBed’ and xenomorphic ‘BreakFaster chair’ look like organic offcuts from eXistenZ. But it doesn’t stop there. Devotees of the auteur will be playing Cronen-bingo here. There’s the aloof, surgical gaze. The graphic, shivering gore. The roll-call of pulpy names (hello, Lang Dotrice, Dani Router and, surely the winner, Brent Boss).

This is where the film may prove divisive: not in the shock and gore, but its sparse, dramatic drive.

And, of course, there’s the stiff, sterile line-readings. For non-converts, this will take some adjusting to. Early on, the dialogue is so prescriptive it sounds like the cast are reading not a script but an instruction manual (the detached tone eventually makes sense: in a future without pain, how else would people speak other than in a spooky, anaesthetised drone?).

So far, so Cronenbergy. There are even some of his trademark black laughs (when Tenser’s invited to an inner-beauty pageant, it’s suggested he enters ‘Best Original Organ With No Known Function’). Mostly, the mood is one of hypnotic doom: heavy-legged, fatigued and feverish. The director is a genre in himself, but Crimes Of The Future identifies as a noir. It’s in the swelling paranoia of Howard Shore’s score. It’s in the peeled, blistered interiors, as ruined as Chernobyl. And it’s in Mortensen’s stony, muted performance. Cowled like Death in Bergman’s The Seventh Seal, groaning dialogue between furball coughs, Tenser slowly unpeels Crimes’ conspiracy of a new plastic-eating species with the detached curiosity of a private eye.

This is where the film may prove divisive: not in the shock and gore, but its sparse, dramatic drive. Cronenberg is so consumed by the horror of us blindly walking into an eco-apocalypse he abandons plot for brooding. All doom. Little suspense.

Does that make the film any less impactful? Weirdly, no. Cronenberg is the Sandman of horror cinema: his nightmare images find an insidious way of worming into the subconscious. Crimes Of The Future is best approached not only with caution, but patience. Slowly, silently, like leaking gas, the film creeps up on you, and you wake up to what a tragic, devastating vision this is. Much of that is down to its haunting closing shot: is Tenser’s smile one of ecstatic hope or destructive acceptance? The future of mankind seems to hangs on his lips, ambiguous and unspoken. If this is Cronenberg’s swansong, as the mournful tone seems to suggest, his final body horror burrows deep, not under the flesh, but in the mind.