Over a decade in the making. Taghi Amirani’s Coup 53 shines a much-needed light on a forgotten chapter in Iran’s past. In 1953, the British and American governments secretly teamed up to remove the left-leaning, democratically elected Iranian Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh and replace him with the Shah of Iran. But Coup 53 is not a dry geo-politics lesson. Instead, Amirani mounts the story with the intrigue, surprises and élan of a spy thriller and creates a film that combines the personal and the political to captivating ends.

It’s a complex, knotty subject, but Amirani’s engaged, likeable presence always pulls you through.

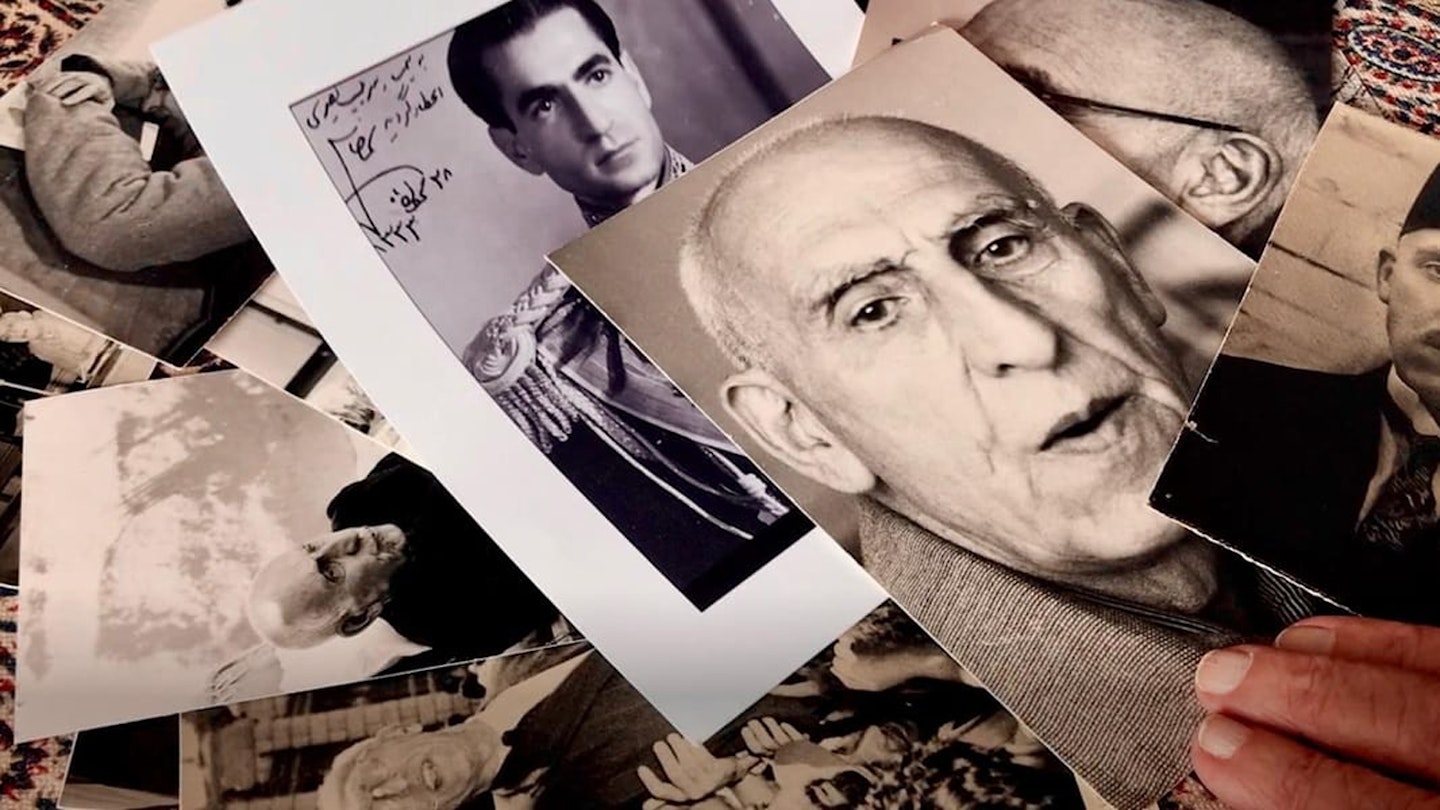

The first act is as much about the finding of the story than the story itself. Putting himself at the centre of the film, we follow Amirani as he visits archives, roots through boxes and boxes of recently unclassified papers and trawls through hours of talking-head interviews. A hymn to dogged determination and old-school journalistic legwork (it has a bit of All The President’s Men about it), the film strikes narrative gold when Amirani, working in cahoots with legendary film editor Walter Murch (The Conversation, Apocalypse Now), discovers the full-length transcripts of ’80s Channel 4 documentary End Of Empire. Present in the transcripts is outspoken MI6 operative Norman Darbyshire, who on paper confirms the British involvement in the coup, but is nowhere to be seen or heard on film. It’s this mystery that sends the film into overdrive.

In a masterstroke, Amirani and Murch utilise Ralph Fiennes (who had worked with Murch on The English Patient) to deliver Darbyshire’s compelling testimony as a talking head. At this point, the film gets to the heart of the matter, a detailed but exciting retelling of the coup itself: the machinations of Winston Churchill and the British government to protect their oil interests; the first failed attempt to replace Mosaddegh with a puppet prime minister; the mysterious murder of a police chief; and then the coup itself, known as Operation Ajax because it was a household cleansing. With little footage of the insurrection itself, Amirani bolsters archive material with thrilling animation of the bloodshed and the executions that followed.

It’s a complex, knotty subject and it occasionally feels like information overload, but Amirani’s engaged, likeable presence always pulls you through. Not just keeping its focus on the coup itself, the film broadens out to count the ripples of how the event affects Middle Eastern politics to this day, and dares to imagine what Iran would have been like if Mosaddegh had not been ousted. It’s a smart, thoughtful end to a powerful, necessary piece of historical detective work.