Now it can be seen again, perhaps the nonsense talk that has surrounded Kubrick's adaptation of Anthony Burgess' dystopian novel will finally evaporate. From the controversy, you'd think the film was like, say, Romper Stomper (1992): a glamorisation of the violent lifestyle of its teenage protagonist, with a hypocritical gloss of condemnation to mask delight in rape and ultra-violence. Actually, it is resoundingly both fable-like and abstract.

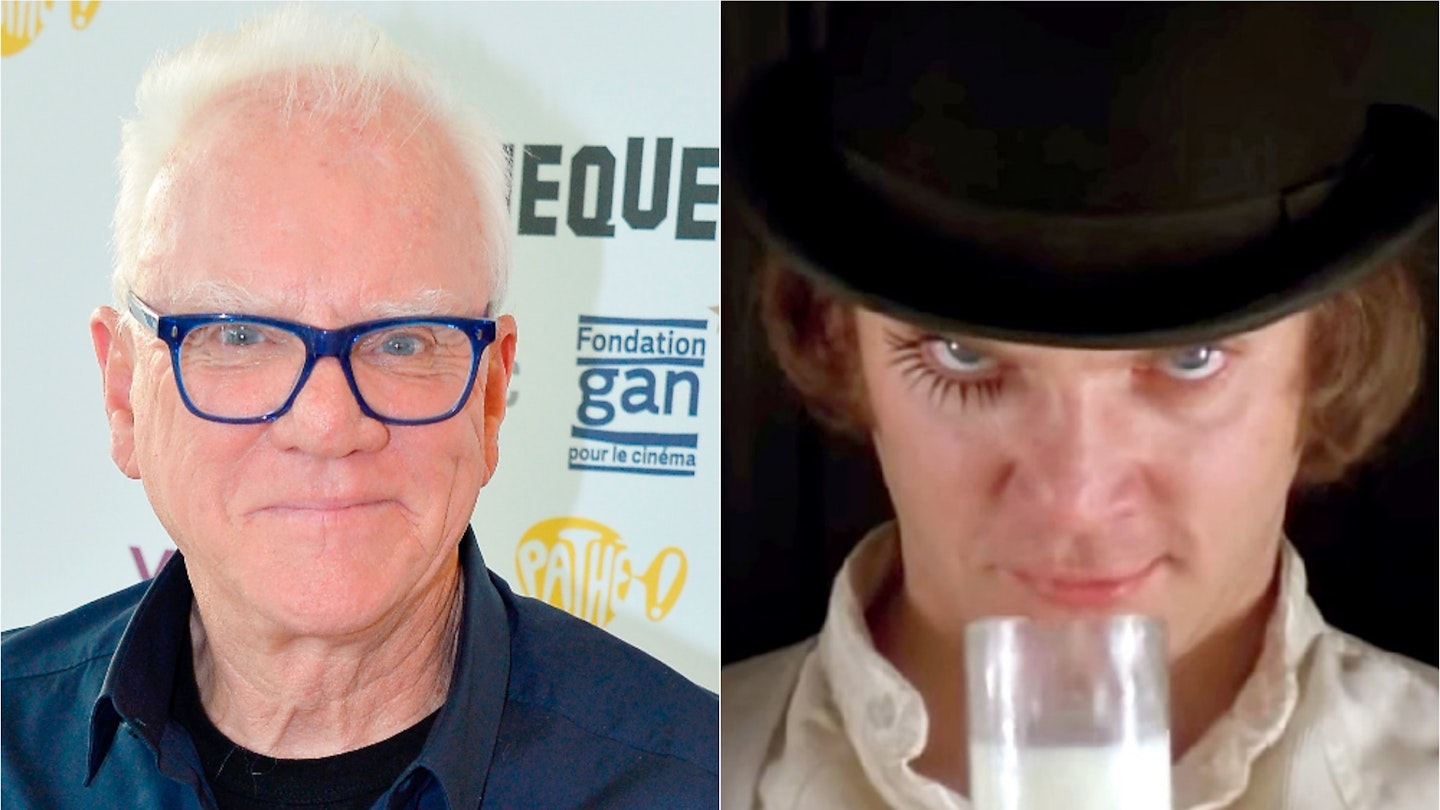

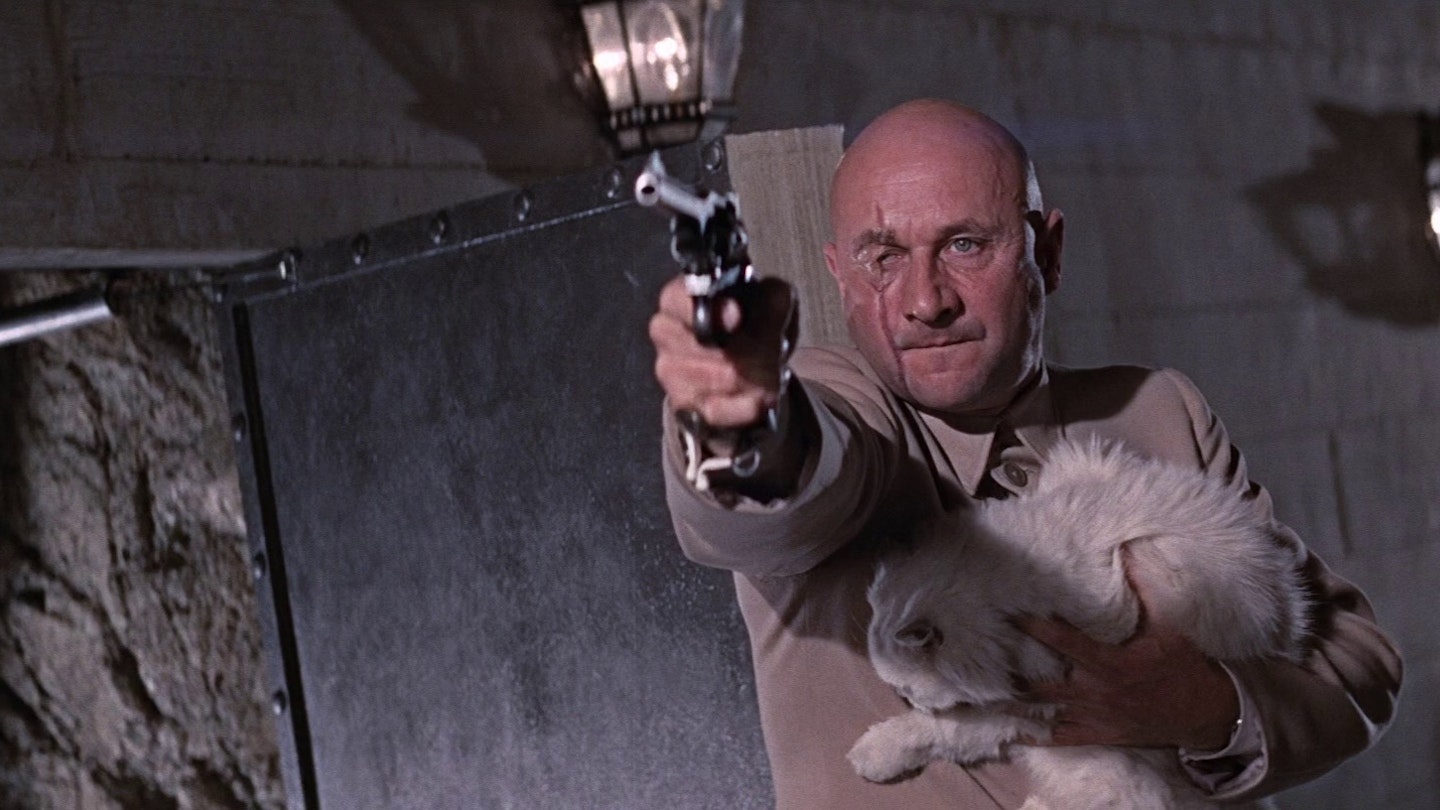

Alex (McDowell), juvenile delinquent of the future, gets a brief 20 minutes anarchic rampage before his apprehension by brutal authorities, whereupon he changes from defiant thug into cringing boot-licker, volunteering for a behaviourist experiment that removes his capacity to do evil. The "cured" Alex finds he has made sadistic monsters of his former victims, and is paid back in full. Alexander (Magee), the last decent man in a corrupt world, is transformed by Alex's assault on his home into a freak, toted about in a wheelchair by Dave Prowse (speaking with his own Bristol voice, for a change). Even more appalling is the realisation that Alex's old "droogs" have gone straight by joining the police, channelling brutishness into the service of the state.

It's all stylised, from Burgess' invented pidgin Russian to 2001-style slow tracks, through sculpturally-perfect sets (like many Kubrick movies, the story could be told through decor alone) and exaggerated, grotesque performances (on a par with those of Dr. Strangelove). Made in 1971, based on a novel from 1962, A Clockwork Orange resonates across the years. Its future is quaint now, with Alexander pecking out "subversive literature" on a giant IBM typewriter, "lovely, lovely Ludwig Van" on vinyl, and Alex stranded alone in a vast and empty National Health hospital ward. However, the world of "Municipal Flat Block 18A, Linear North" is very much with us: a housing estate where classical murals are obscenely vandalised, passersby are rare and yobs loll about with nothing better to do than hurt people.