Alfred Hitchcock's second outing for his Transatlantic Pictures company was adapted by the Scottish playwright James Birdie from a novel by Helen Simpson, who had co-written the 1929 thriller, Enter Sir John, on which Hitchcock had based Murder!.

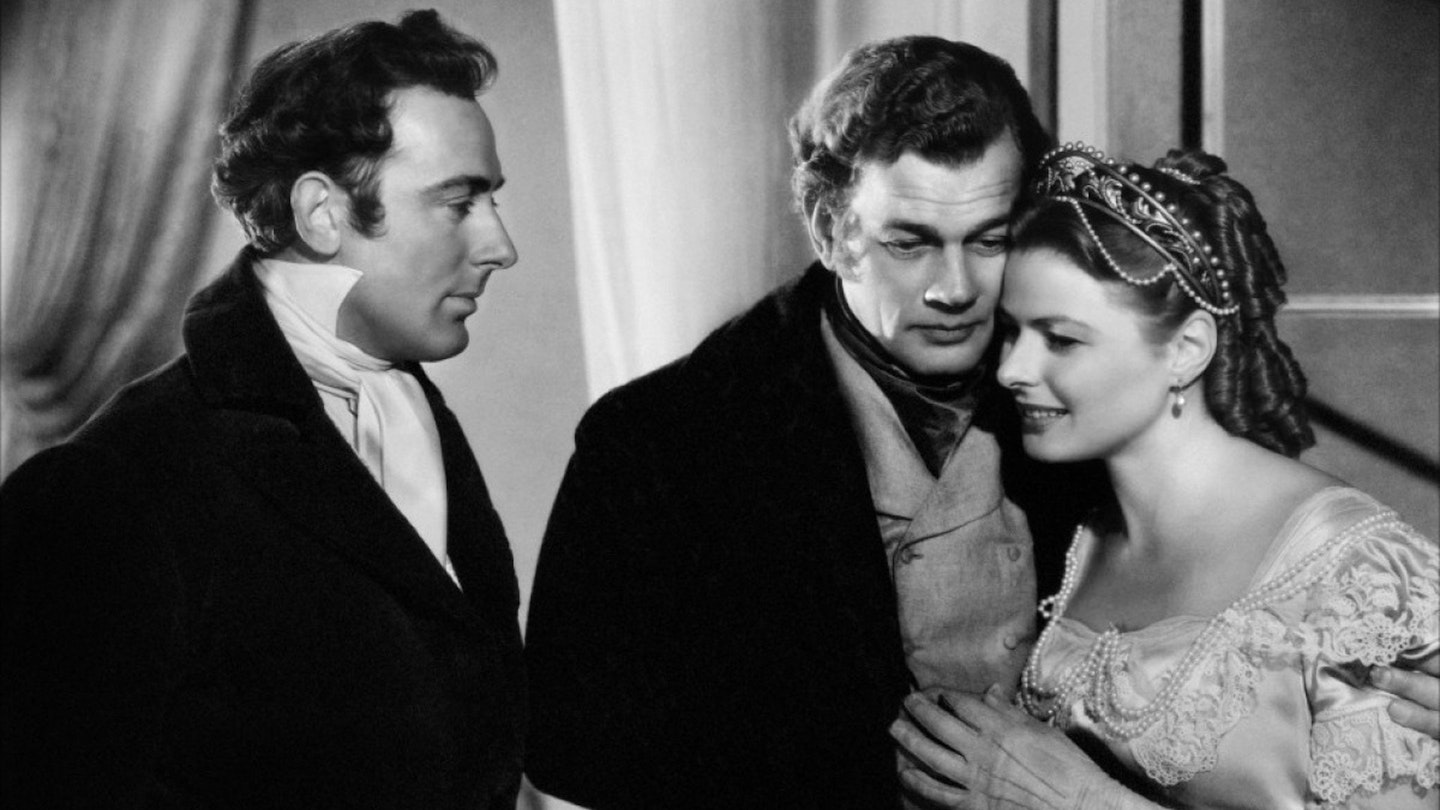

Echoes of Rebecca reverberate through the action, as Ingrid Bergman's unhappy bride finds herself imprisoned in an imposing pile (whose name Minyago Yugilla' translates as Why Weepest Thou?') and imperilled by an envious domestic. But, despite the fact that Under Capricorn* *was Hitchcock's first British-made feature in a decade, it singularly failed to replicate the success of his Hollywood debut.

No sooner had Hitch arrived at Elstree Studios than an electricians' strike broke out and lingering resentments were exacerbated by his decision to shoot in complex long takes that placed additional pressure on the crew. The loss of a further fortnight to bad weather scarcely improved tempers and Hitchcock was then forced to complete the final scenes to a rigid deadline caused by the imminence of an incoming production. Having returned to Hollywood, Hitchcock and his partner Sidney Bernstein then squabbled via telegram over the cutting of the picture, which ended up costing $2.5 million.

Worse was to follow, however, as within days of the film's US opening, news broke of Bergman's adulterous affair with Roberto Rossellini (whom she had met during the shoot) and Catholic pressure groups demanded its immediate suppression. However, it was the bad press that caused the movie to flop and revert back to the bank that had financed it.

Yet, this acerbic historical is bleakly compelling. Jack Cardiff's Technicolor photography, Tom Morahan's sets, Roger Furse's costumes and John Addinsell's score were all splendid. Moreover, the action perfectly bore out Hitchcock's contention (which tellingly inverts Jean Renoir's belief that everyone has their reasons) that `everything's perverted in a different way'. Thus, Henrietta has both beauty and a tendency to self-destruct; Flusky possesses decency, but no passion; Charles combines civility and covetousness; while Milly takes loyalty to the point where she's prepared to kill to prove it.

No classic, perhaps, but long overdue a critical re-evaluation.