The latest in a number of horror franchises that have received the ‘legacy-quel’ treatment — soft reboots that sweep aside what is viewed as messy and disposable canon (think David Gordon Green’s Halloween) — Nia DaCosta’s new take on Candyman directly continues the story of the original and most beloved entry in the series. The film revives Bernard Rose’s 1992 cult horror, continuing its mythologising of buried, collective historical trauma in the form of its eponymous vengeful spirit, but also attempts to self-reflexively engage with the missteps of its predecessor. And where the original used gentrification and academia as a route into discussions of government-enforced social barriers, DaCosta builds upon how this has continued into the present day.

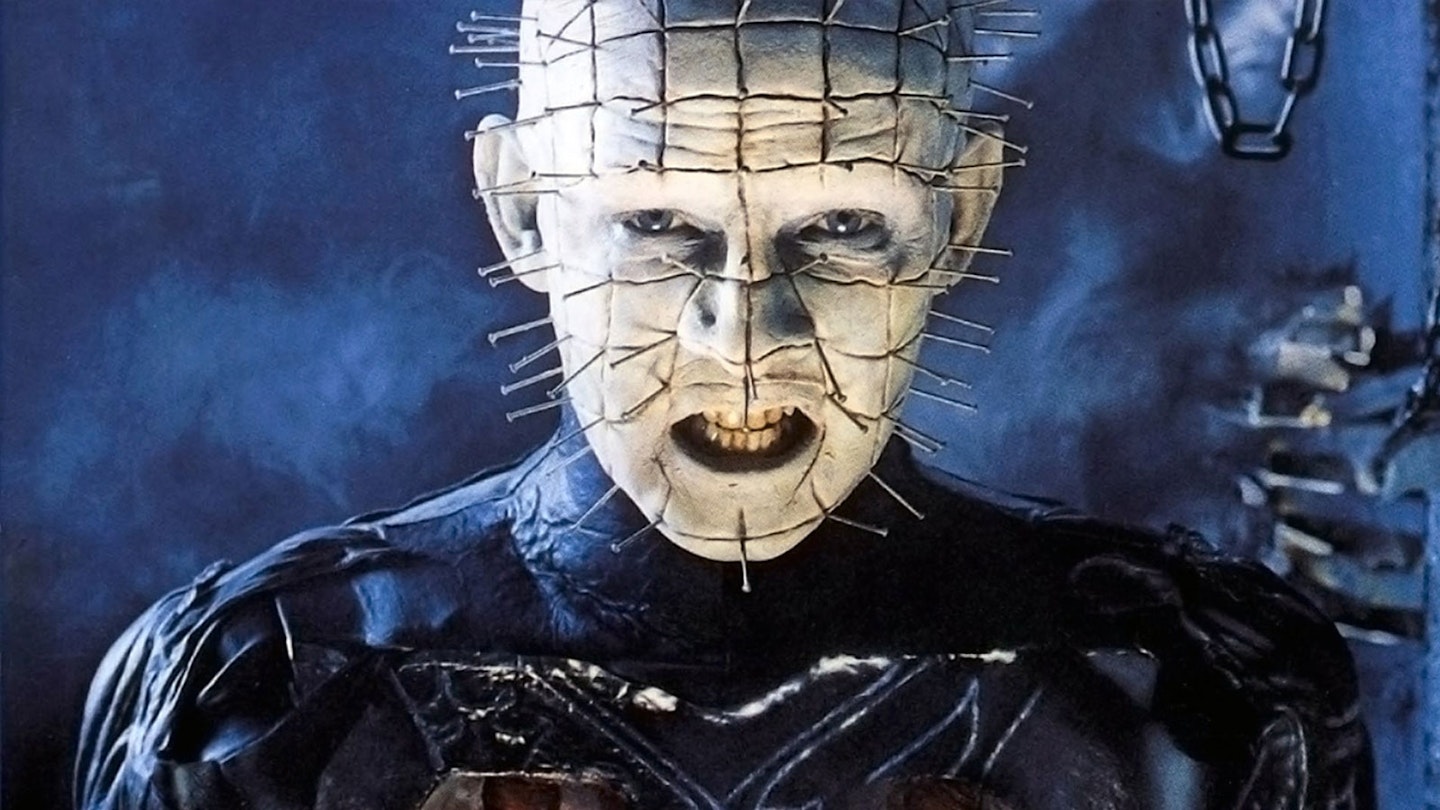

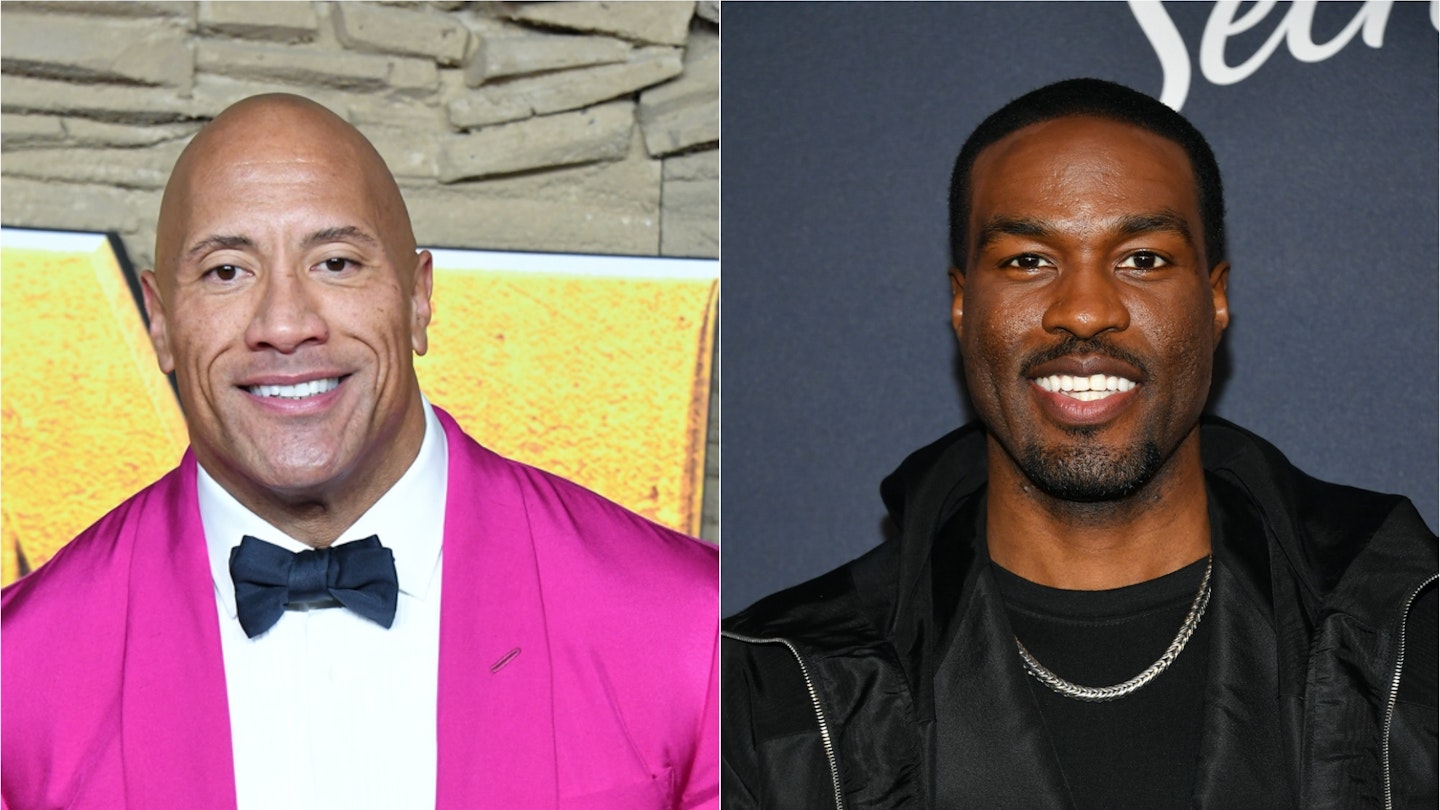

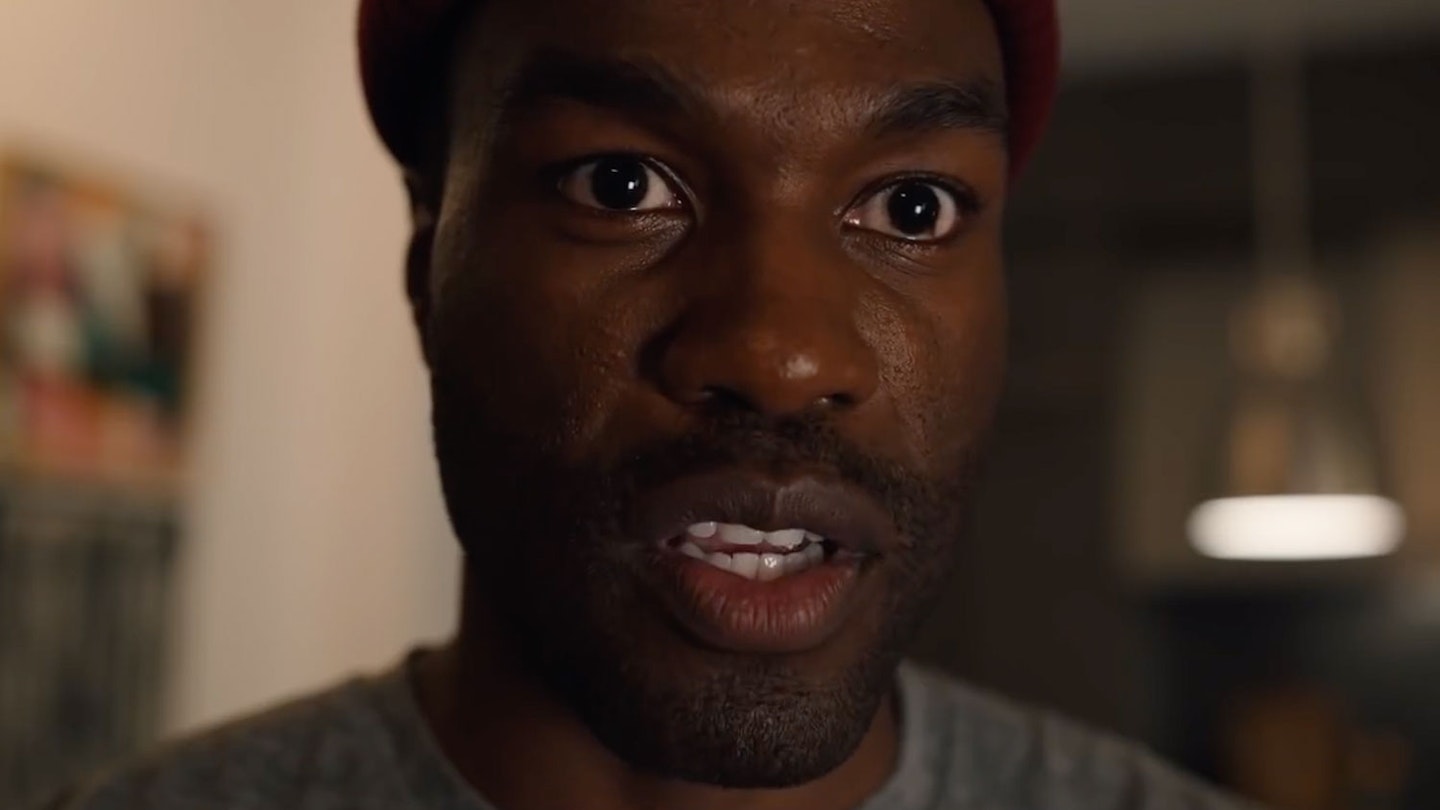

The film returns to a now-gentrified Cabrini Green, the location of the first film. Through a new art project, Anthony (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II) unwittingly unleashes the Candyman, who kills anyone who summons him by saying his name five times in a mirror. With her 2018 debut feature Little Woods, DaCosta has experience in navigating socio-economic boundaries and broken governmental systems with nuance. Candyman would seem a perfect continuation of her interests. It’s an interesting expansion on the character’s mythos, taking the stronger elements from its derided sequels — though anyone looking forward to seeing Tony Todd back in the role again might be disappointed. Where the first film used the spectre as a commentary on the demonisation of projects and council housing, DaCosta’s film is recalibrated as a response to the aftermath of such negligence, a reminder of who lived here before the fancy glass flats appeared. Further still, DaCosta, Get Out director Jordan Peele and Win Rosenfeld’s screenplay is also interesting in the ways in which it acts as a corrective to the messier parts of the ’92 Candyman that muddied its overall thesis, working to point the spirit’s vengeance and violence back towards his original oppressors. The original Candyman protagonist Helen’s role in the story is intentionally told through unreliable narrators, itself an urban legend in the context of this new film.

Nia DaCosta visually places the horror amongst the invasive architecture of gentrification.

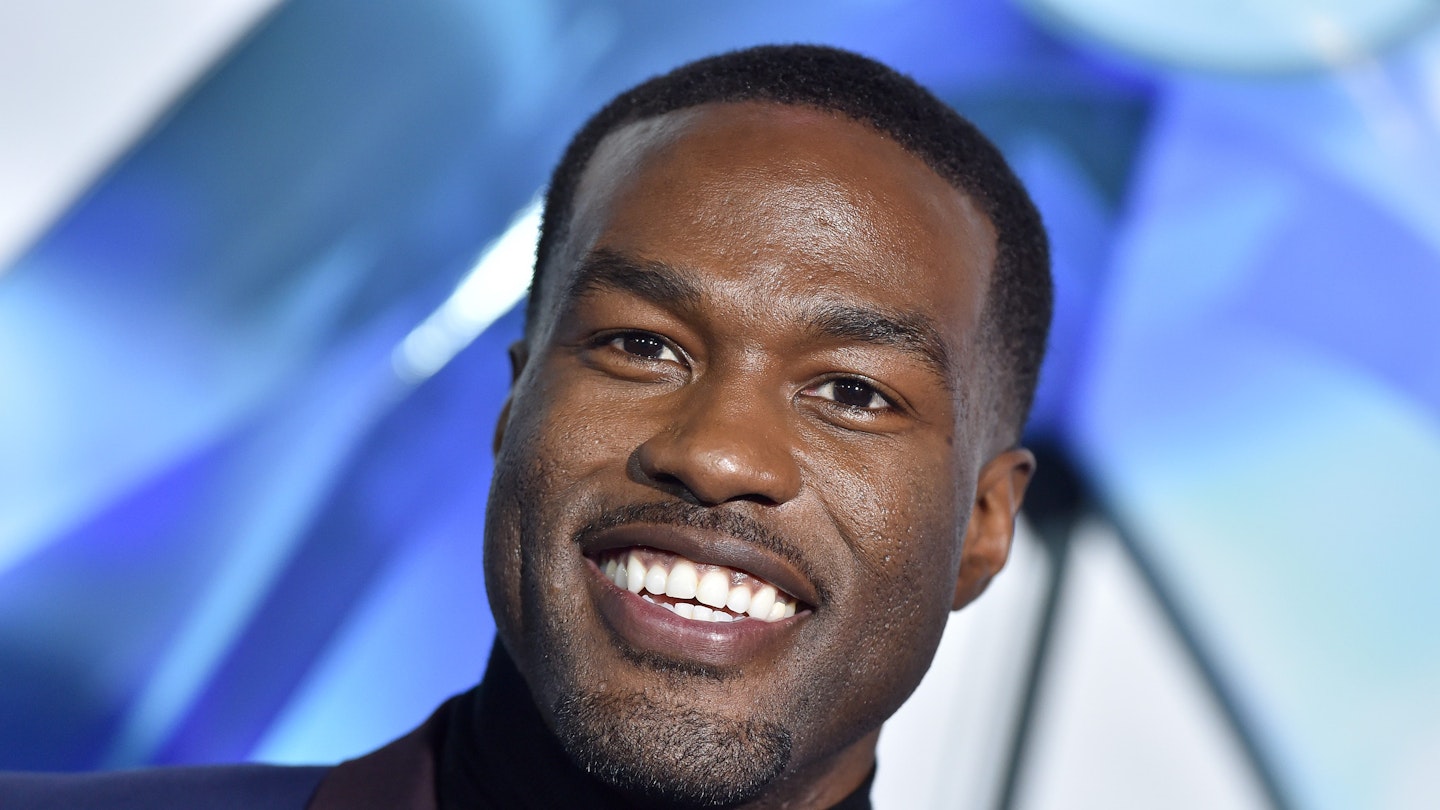

This attempt to neaten up the meaning of its predecessor for a new audience is solid, but it then overcorrects, as every subsequent scene seems as though it contains a conversation detailing the revisionism. DaCosta’s film seems to pre-empt such critiques (amusingly, an obnoxious white art critic demeans Anthony’s work as didactic), but it doesn’t prevent the transformation of subtext into big, bold text that feels like a studio demanding some hand-holding. It feels like a similarly pre-emptive shield against misinterpretation, and it becomes stifling, not letting its performances do the work. Abdul-Mateen II and Colman Domingo, as a Cabrini Green resident still preaching the Candyman urban legend, are particularly magnetic, channelling deep sadness and rage like a spiritual possession, one that quite literally eats away at Anthony as his art and his engagement with historical traumas becomes an obsession. Teyonah Parris’ Brianna adds an intimate and personal connection to the film’s collective grieving, and its transformation into anger. Despite its lack of subtlety the scripting is frequently funny too, one highlight being a character wondering who would be fool enough to enact the catoptromancy that summons Candyman, before cutting to a group of white mean girls in a school bathroom.

It’s also visually compelling when it becomes less concerned with explaining itself. Cinematographer John Guleserian conjures discomfort from the sight of the shiny luxury apartments that have papered over the grime of the first film — the opening an unsettling mirror to the original Candyman’s ominous overhead shots of high rises, turning them into otherworldly presences by shooting them from below and inverting the image. One of DaCosta’s finest touches is the intermittent shadow-plays recounting various urban myths, a nod to an oral tradition of storytelling that preserves the repeatedly decimated history of African Americans. While doing this, it reaches the existentially terrifying fatalism of its predecessor, in how it emphasises inevitable, continuing cycles of white supremacy and continuing inter-generational pain. Most presciently, for every story about Candyman, there’s one equally violent one about the Chicago PD that shortly follows it, their actions more unambiguously evil.

DaCosta visually places the horror amongst the invasive architecture of gentrification, the looming glass towers feeling as much of a threat as anything else in the film. One of the more memorable kills is portrayed in a long zoom out, dwarfing the victim in the window of their expensive apartment in a mixed-budget complex, the kind that Cabrini Green was replaced with. If the early stages of the film are too concerned with explaining the meaning of the Candyman himself, at least the consequences of his summoning are appropriately messy, both in the wince-inducing bloodshed and whom specifically it’s targeting, a collective vengeful anger unleashed on anyone who dares mention it in jest. It’s fun to see the spirit change from something stumbled upon to something summoned with purpose, in the genuinely pointed and provocative moments that conclude the film. It’s a shame, then, that just as it establishes a new identity, it’s done, its time cut short by its various stolid lectures.