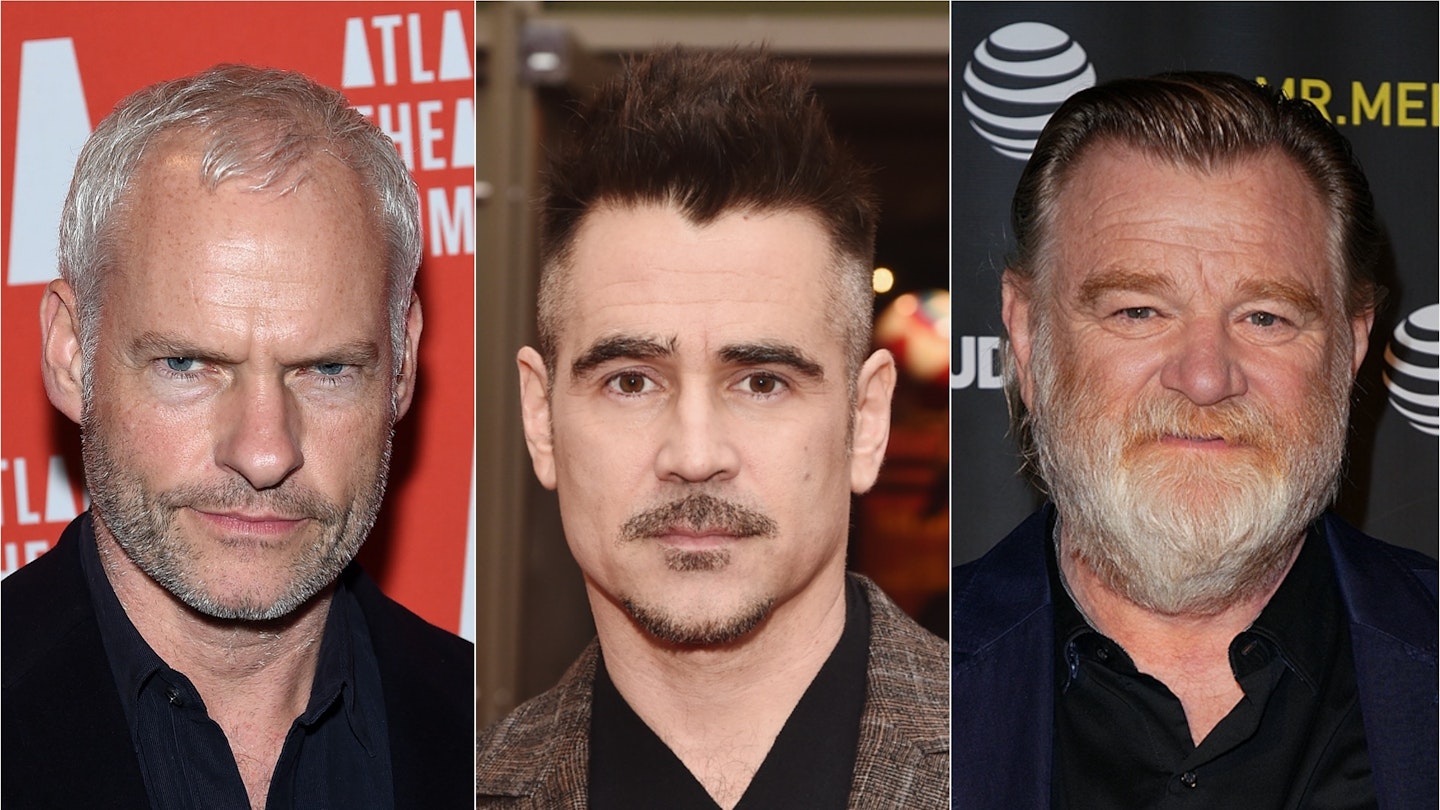

In Bruges is not for everyone. Like its characters, it’s unruly, foul-mouthed and has a weird sense of humour and no concept of good behaviour. But even if those caveats whet your appetite, there’s another hurdle to overcome: the dread phrase “British gangster movie”. In America, Martin McDonagh’s genre-stretching film already made a cautious bow at the box office, alienating some higher-brow critics who sniffed at its wayward and irresponsible tone but finding a surprising amount of support from grassroots cinemagoers, despite a very limited release.

It’s a strange film. Going into it, there are all kinds of questions you might be asking yourself - isn’t this just Sexy Beast meets Pulp Fiction? Isn’t Brendan Gleeson a bit above this kind of thing? What is Colin Farrell famous for anyway? - but, coming out, all that remains are the positives. In fact, one online review - posted on Metacritic.com by user “Kristina” - accidentally nails its perverse charm while trying to slam it. “Bad acting, unlikeable and underdeveloped characters, bizarre and stupid situations, too much blood, ridiculous ending,” she raged. But it wasn’t all bad news. “My husband and I were both disappointed in this movie,” she concluded, “but the one good thing about it was that we learned something about Bruges and would like to visit there someday.”

This barbed compliment would no doubt amuse writer-director McDonagh, and, more to the point, sounds like something one of his characters might say. Once you’ve seen the film (and you must, even if just to disagree with this very, very positive review) hopefully it’ll amuse you too, thinking of the individual who fidgeted and tutted through 100 minutes of swearing, violence and profane epistemology - not to mention rampant class-A drug and dwarf abuse - and after all that still fancied a nice city break. It’s fittingly bathetic too, because, though it superficially takes place in the same cartoon underworld as Lock, Stock and its offspring, In Bruges has more in common with a Mike Leigh film than any of Guy Ritchie’s.

Part of the reason for this is that McDonagh’s background, like Leigh’s, is in theatre, which explains both In Bruges’ weakness and strengths. Like a good stage play, McDonagh’s film explores character through dialogue as well as action, and though this makes it somewhat static - even taking into consideration its frenzied, blood-spattered showdown - In Bruges is able to sneak in some heavyweight questions under the radar.

Though it speaks of contract-killing and cocaine-dealing, scoring and whoring, this surprisingly thoughtful film leaves plenty of ideas to be mulled over later, particularly those involving notions of audience identification. In Bruges is a film no Hollywood studio would ever make; it’s a film in which not one single foregrounded character - even the duplicitous love interest (the otherwise adorable Poésy) - is worthy of our sympathy, but by its enigmatic ending it has us, if not cheering them on, then definitely accepting them, and maybe even feeling genuine, if misplaced, affection for them.

The key line arrives a little way into the movie. Ray and Ken have arrived in Bruges and, while Ken is enjoying the majesty of the local architecture, Ray is behaving like a petulant teen. “If I’d grown up on a farm and was retarded, Bruges might impress me,” he sulks. “But I didn’t, so it doesn’t.” Though funny, this kind of banter isn’t exactly new in the general field of gangster movies, let alone the UK kind or its rarefied fish-out-of-water subgenre (see - or rather don’t - the Brighton-set Circus). However, when Ray looks across the town’s cobbled courtyard, where a camera crew is shooting, the film gets a much-needed jolt. Diverting from the smart-arse blueprint, Ray suddenly becomes a child again, his face melting with delight. “They’re filming midgets!” he squeals.

Here, we enter the first of the film’s carefully laid minefields. The politics of the vertically challenged are as complex as they’ve ever been, so without wishing to offend people of size, we’ll stick with the film’s terminology for now (although Ray is told that “midgets” prefer the word “dwarf”). Jimmy, the “little fella” being filmed - an incredibly game Jordan Prentice, whose early starring role in Howard The Duck (1986) suggests that he may actually be physically incapable of embarrassment - is a curveball thrown so elegantly by McDonagh that his fall from grace coincides smoothly with our growing fondness for Ray and Ken. During the film’s hilarious lads’-night-out scene, it takes us a while to realise that Jimmy, even to those who saw Peter Dinklage’s unsentimental performance in The Station Agent, isn’t just some afflicted victim to be pitied, he’s a flesh-and-blood guy like everyone else. And he’s a total arse.

Of the central pair, at first we’re drawn to the avuncular Ken rather than the goofy, irritating Ray. But once his terrible secret is revealed, Ray suddenly seems more vulnerable, perhaps even more romantic, than his thug shell suggests. It’s partly in the writing, but more importantly it’s in Colin Farrell’s sad, scared eyes, in a performance that reminds us that he actually hasn’t really had a chance to do much of this kind of thing over the past eight years or so. He’s joined armies and led them, played US cops and robbers, but with the exception of 2003’s Intermission he hasn’t done a human comedy, let alone the black kind, and the results here suggest he ought to do quite a bit more.

But Farrell isn’t carrying this engagingly digressive caper alone, and Gleeson makes the perfect foil, simultaneously despairing of, and caring for, his troubled, trigger-happy sidekick. While Farrell fits the stereotypical profile of the hip young gunslinger, Gleeson is the very antithesis, but just when you’re getting used to this offbeat casting, McDonagh plays his trump card. If you haven’t seen Ben Kingsley in Sexy Beast, the payoff will be more effective, but even if you have, Ralph Fiennes’ performance as grouchy crime boss Harry is still something to be savoured. With a Peter Cook drawl and dressed in Essex slacks and slip-ons, Harry is the true snake amid this already unsavoury ensemble, phoning Ken with his secret mission in Bruges while Ray is supposedly in the toilet (“Is he having a poo or a wee?” the oily Harry rather creepily asks).

With its three protagonists in place, In Bruges begins its frantic final act, which is where some of its artfully packed contents start to spill out, and the simple pleasures of its character studies give way to overexcited intrigue, tragedy and an inevitable climactic shoot-out. Still, this is a minor gripe about a film which takes a genre that shouldn’t be allowed any more, never mind encouraged, and fashions something provocative and original in its thinking.

Despite some deliberate nods to medieval theosophy, and a coda that’s more arthouse than grindhouse, In Bruges isn’t exactly Samuel Beckett’s Get Carter - let’s face it, if Samuel Beckett had written Get Carter, Carter wouldn’t have turned up, would he? But to fill that existential gap, both literally and figuratively, this savvy, punk-rock pistol opera will do very nicely indeed.