While so many authors suffer the translation to the big screen, their words too sprawling to whittle down to some sensible filmic order, Graham Greene’s wiry, evocative fiction makes the journey more or less intact. Alongside The Third Man and The Fallen Idol, this strident, shadowy seaside noir is further mark of excellence in his adapted canon.

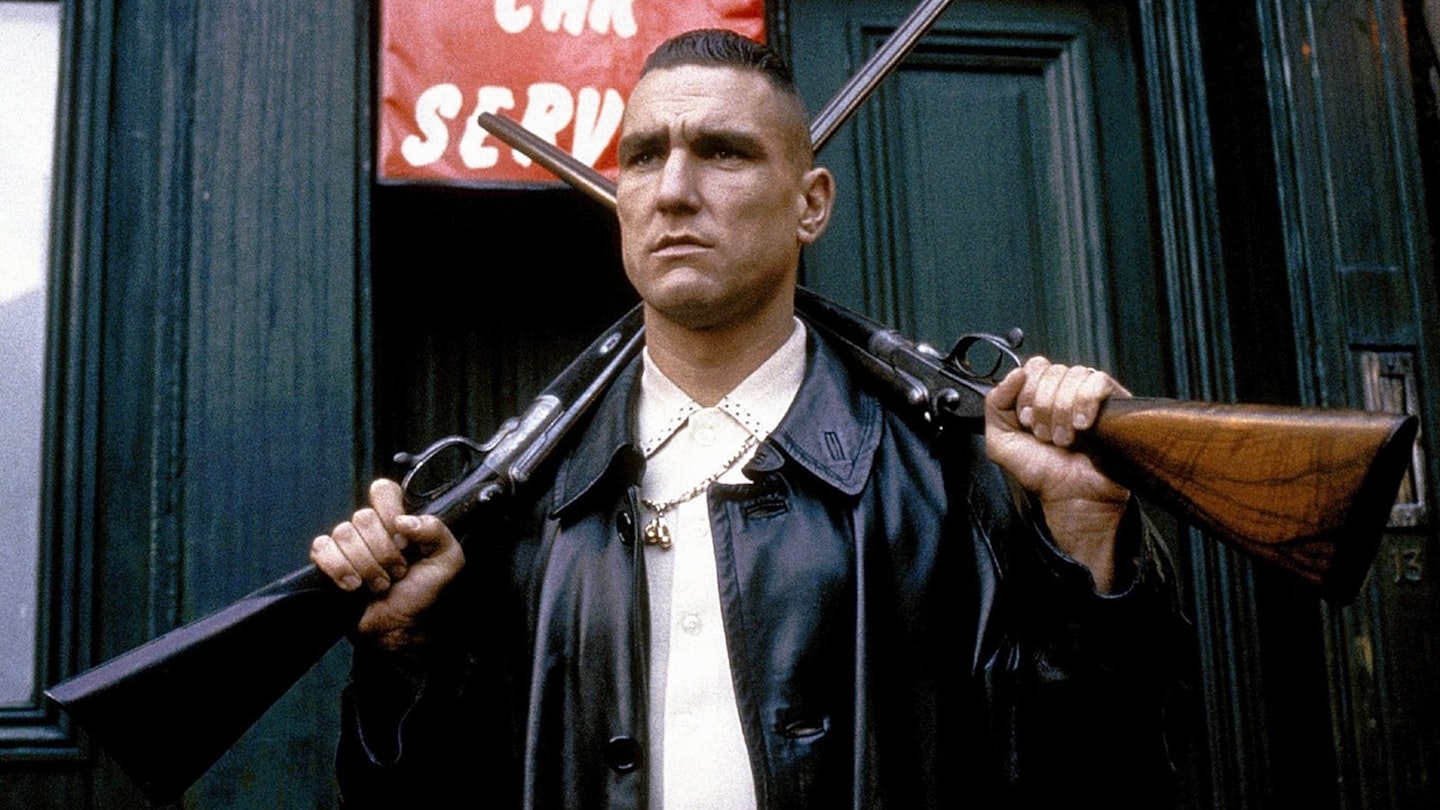

The trick seems to be to grasp first and foremost the complex natures of his characters, then let the plot spill about them. Getting Pinkie right was essential, he stands as possibly Greene’s most memorable character, a lowlife gang leader barely beyond his teens, shirking his good Catholic upbringing, his soul lost to small ambitions and petty crime. Richard Attenborough, then so fresh faced, gives him real edges, driven by an uncomfortable urgency he can never settle. There’s an unreachable itch in is Pinkie, but he has charisma, albeit a stern, violent kind of magnetic force.

Into his deadly orbit falls the lithe naïf Rose, a waitress dappy for love, determinedly upholding her Catholic dues carrying an unbidden knowledge that could sink Pinkie. So he works her vulnerability, offering her the sham of true love, which she buys wholesale. Carol Marsh exposes both her vulnerability and stalwart heart. The film is cast well across the board — William Hartnell, Nigel Stock and Wylie Watson as Pinkie’s weasley band, and Hermione Baddeley as Ida, the brassy broad who is onto Pinkie.

Director John Boulting brings the fabled Greeneland, that vile landscape ripened on sin and betrayal at the black heart of all his novels, to sensuous life. You feel the throb of Brighton’s cramped summer streets, the raddled squawks of hungry gulls, and the sizzle of frying food. Yet beneath this papered veneer of normality, lurks a seething underworld, shorn of glamour, where righteousness will finally usher the film to its fateful, cruel conclusion.