There’s a scene in David Lynch’s Blue Velvet that takes visual shorthand to new heights: a shot of the hero’s family TV set, it purports to be footage from a ’40s film noir thriller. In crisp black-and-white, we see a hand holding a gun and a shadowy figure who appears to mounting a set of stairs. You could waste a lot of time trying to find out which movie it’s from, but in all likelihood, it doesn’t exist. With one fake shot, Lynch is capturing the essence of the entire film: how crime, threat and menace actually titillate us. Whose hand is it? Whose gun? Where is it going and why? This teasing fragment tells us a lot about the nature of entertainment and our rapacious appetite for thrillers, cop flicks and trashy whodunnits.

With Brick, first-time director Rian Johnson appears to have taken that one observation, then stretched it, twisted it and salted it to create one of the most original and entertaining movies of the year so far. You might (hard)boil it down to The Outsiders as scripted by classic pulp writers Dashiell Hammett, James M. Cain or, most obviously, Raymond Chandler. But more simply, Brick understands the beauty of an honest mystery, elegantly mounting a series of clues — with twists and red herrings along the way — before weaving it all together for a mind-reeling climax.

Be warned, though: it does take some time for the film to settle, because Brick has one major gimmick in its grasp. Though shot in lustrous colour and filmed in the wide-open, sunny suburbs of San Clemente in California, Johnson’s high-school teens converse in a lingo that owes more to tough-guy private dick Sam Spade than the Valley-speak of Clueless and American Pie. Cops are “bulls”, drug addicts “dose” themselves and “duck soup” is pretty hard-to-see slang for “easy pickings”. It’s not always convincing, and the mostly unknown cast sometimes struggle with it, but Brick sticks with its convictions, and after a good 20 minutes, all the jive talk sifts into the background.

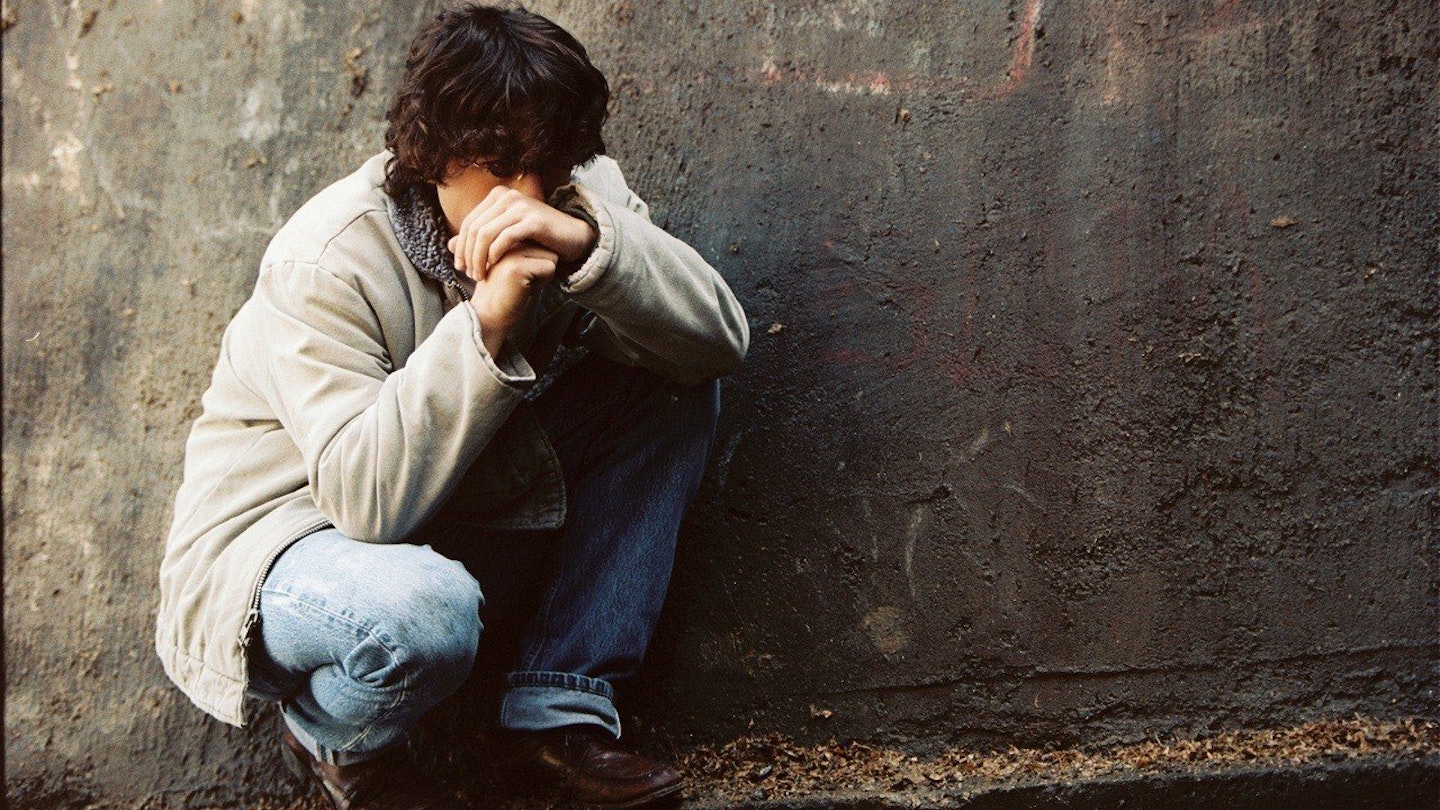

Chiefly responsible for the movie’s success is a strong lead performance by Joseph Gordon-Levitt. As loner Brendan Frye, a maverick defined by his preference for eating lunch by himself round the back of the school, the former Third Rock From The Sun star firmly establishes himself as an evolving talent to watch. A kid who’s prone to the rough stuff, Brendan is a sad but dedicated avenging angel, hung up on his poor ex, Emily (Emilie de Ravin), and determined to save her from the in-crowd of chic drug users and pushers whose approval she so desperately craves. Which is vital to a proper understanding of Brick’s basic mechanism, because although on paper it seems like a hollow stylistic exercise, it has plenty to say about the world of teenagers. Next to no adults appear (just two, and they’re hardly proactive), and Brendan’s hunched-up isolation stands in stark defiance of those around him, including Kara (Meagan Good), the showgirl with a human lapdog forever in tow, and femme fatale Laura (Nora Zehetner), the beautiful girl from the beautiful world of the beautiful people.

Brendan circles this demi-monde like a shark, unfazed by the glamour, watching with unimpressed eyes as the likes of Laura’s boastful jock-dork boyfriend pimp out their dignity for popularity. But not being with the winners doesn’t make Brendan a loser; he has equal contempt for sad-sack stoner Dode (Noah Segan), a feckless punk with a connection to Emily. Brendan’s loathing of these cliques and clans is what enables him to transform from the quivering wreck who finds Emily’s body into a Terminator-style vigilante: his mission is not simply to bring down justice, but to play all the angles and be sure that everyone who’s had a hand in Emily’s downfall gets their own sweet, assured and tailor-made destruction.

True, it gets convoluted at times — though it’s not quite as murky as Howard Hawks’ 1946 adaptation of Chandler’s The Big Sleep, which even the novelist himself couldn’t fathom. Johnson follows his own story with a fast-paced logic that sometimes leaves question marks dangling, but all those points add a little more to ponder and savour once the bigger conundrum is finally cracked. It will certainly split people into those who buy the conceit and those that don’t, those who see daffy, sub-Bugsy Malone drivel where others gobble up its Usual Suspects goose-chase and debate its Donnie Darko-like demands for interpretation. But Brick wasn’t made for everybody. It’s a film that nobody should agree on. Like Brendan himself, we should just be proud to differ.