There was a point, peaking in the mid-2000s, when you could hardly move for someone unwisely puffing up their chest, adopting a rictus grin and screeching into your ear: “Veery naaice!” Borat has been so defined by his infinitely repeated catchphrases that it is easy to forget how the insane original 2006 film practically invented a genre: the narrative prank comedy. Viciously skewering the ugliest underbellies of American culture with a ridiculous stereotype of Eastern European backwardness, Borat — with contributions from the likes of Alan Partridge’s Peter Baynham and Joker’s Todd Phillips — turned Sacha Baron Cohen’s late-night Channel 4 TV-sketch character into a bona fide cultural phenomenon, as slyly satirical as it was stupidly funny.

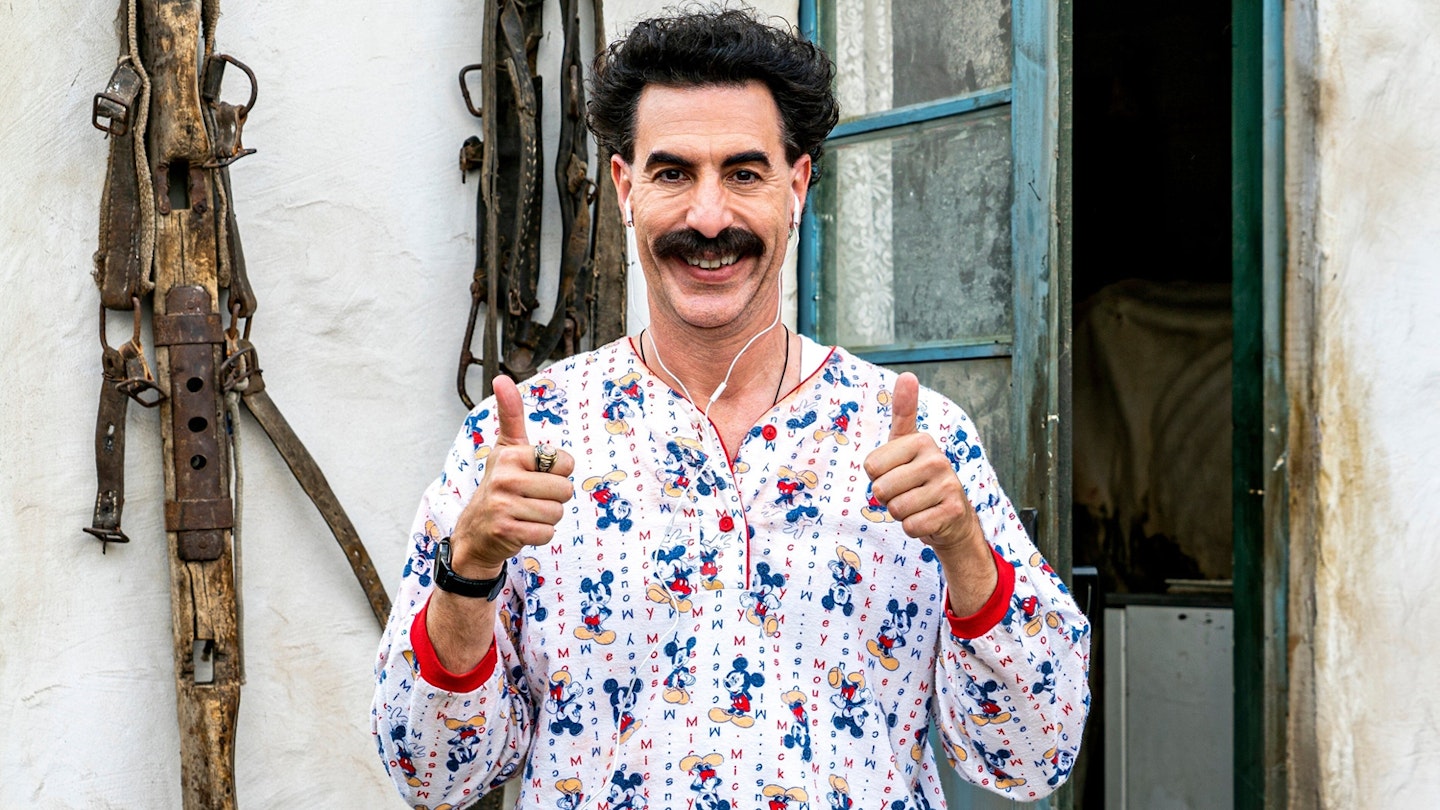

Fourteen years later and Borat now an internationally recognised icon, the concept must change; as the film acknowledges, it’s hard to do a prank when everyone’s in on the joke. So, Borat — having spent the intervening years in a Kazakh hard labour camp, for bringing shame on his country —largely adopts a series of disguises for the sequel, leaving a lot of the pranks to his daughter (or “non-male son”, as he puts it), Tutar, played by Bulgarian newcomer Maria Bakalova.

It’s remarkable how it spins plates between ridiculous crudeness, pulse-quickening shock tactics, and pointed political commentary.

Many of the first film’s tricks are simply repeated or repurposed. As before, Cohen delights in exposing the casual bigotry of average Americans: witness the Southern shop owner who helpfully assists our hero pick out the best tools for “murdering gypsies”, or the cake-shop owner who cheerfully agrees to write “Jews Will Not Replace Us” in icing. Sometimes, it’s just about ruffling some stuffy, highfalutin feathers, as in the fairly extraordinary “fertility dance” that Borat and Tutar perform to a stunned debutante ball in Macon, Georgia. And sometimes, yes, it’s just going for the cheapest laugh possible, like the dick-pic sent — by fax — to an unassuming post office manager.

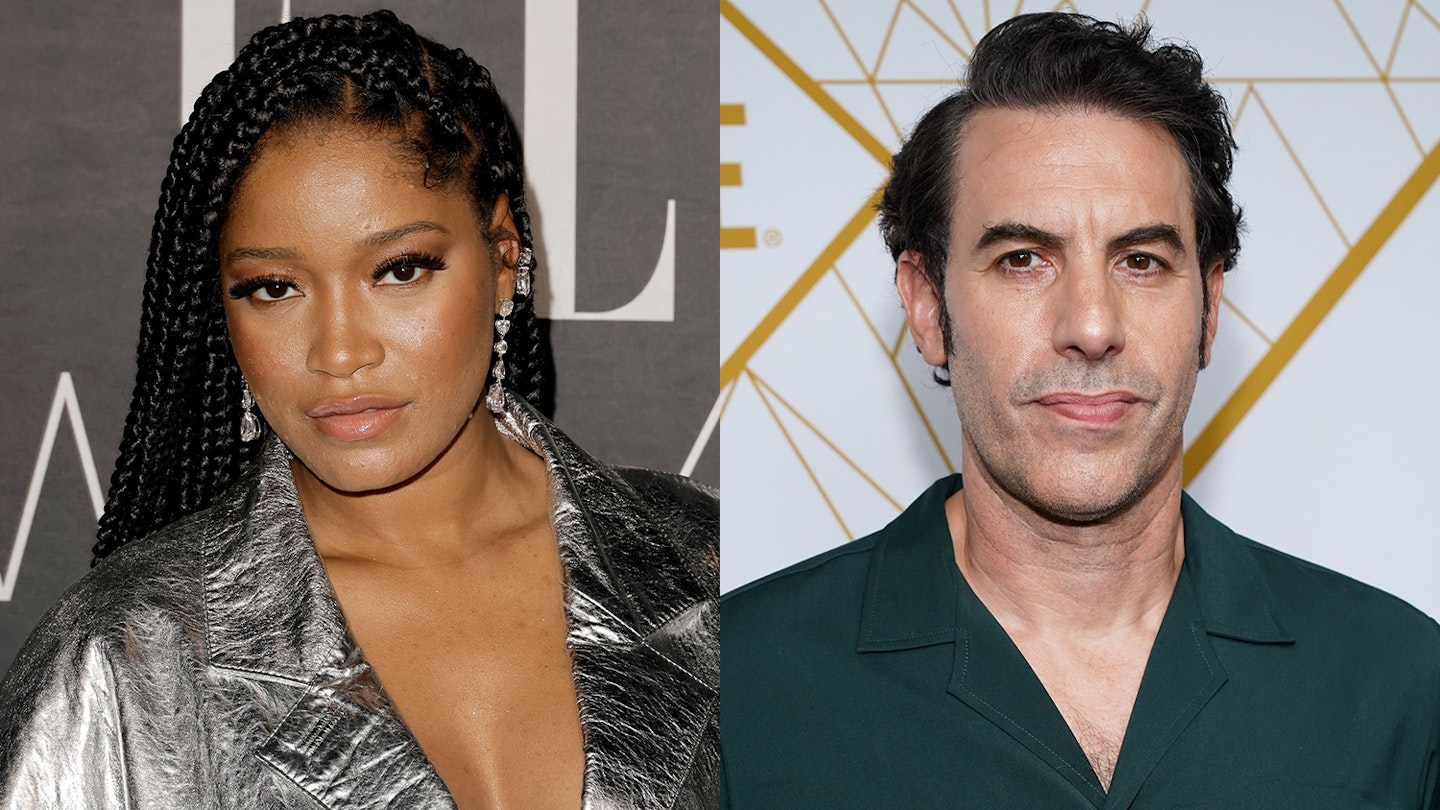

Some stunts feel like they’re there to stall for time (Borat cuts a man’s hair! Borat is confused by smartphones!), and one exchange with an actual Holocaust survivor feels a little misjudged, but otherwise it’s remarkable how much the film packs in, and how it manages to spin plates between ridiculous crudeness, pulse-quickening shock tactics, and pointed political commentary. Cohen’s total fearlessness as a performer is still really something to behold — the man sometimes wore a bulletproof vest to make this film — matched only by Bakalova’s instantly winning improvisational skills.

The film was rushed into a pre-election release, with a closing title card imploring viewers to vote, and while the vigorously juvenile humour (choice quote: “I can open a beer with my smokehole!”) is unlikely to tip the electoral scales or persuade any floating voters, it does feel like an appropriately messy, bizarre snapshot of a country in a unique kind of chaos — an artefact of the strangest year imaginable, told by the strangest possible chronicler. As you might have said in 2006: veery naaice!