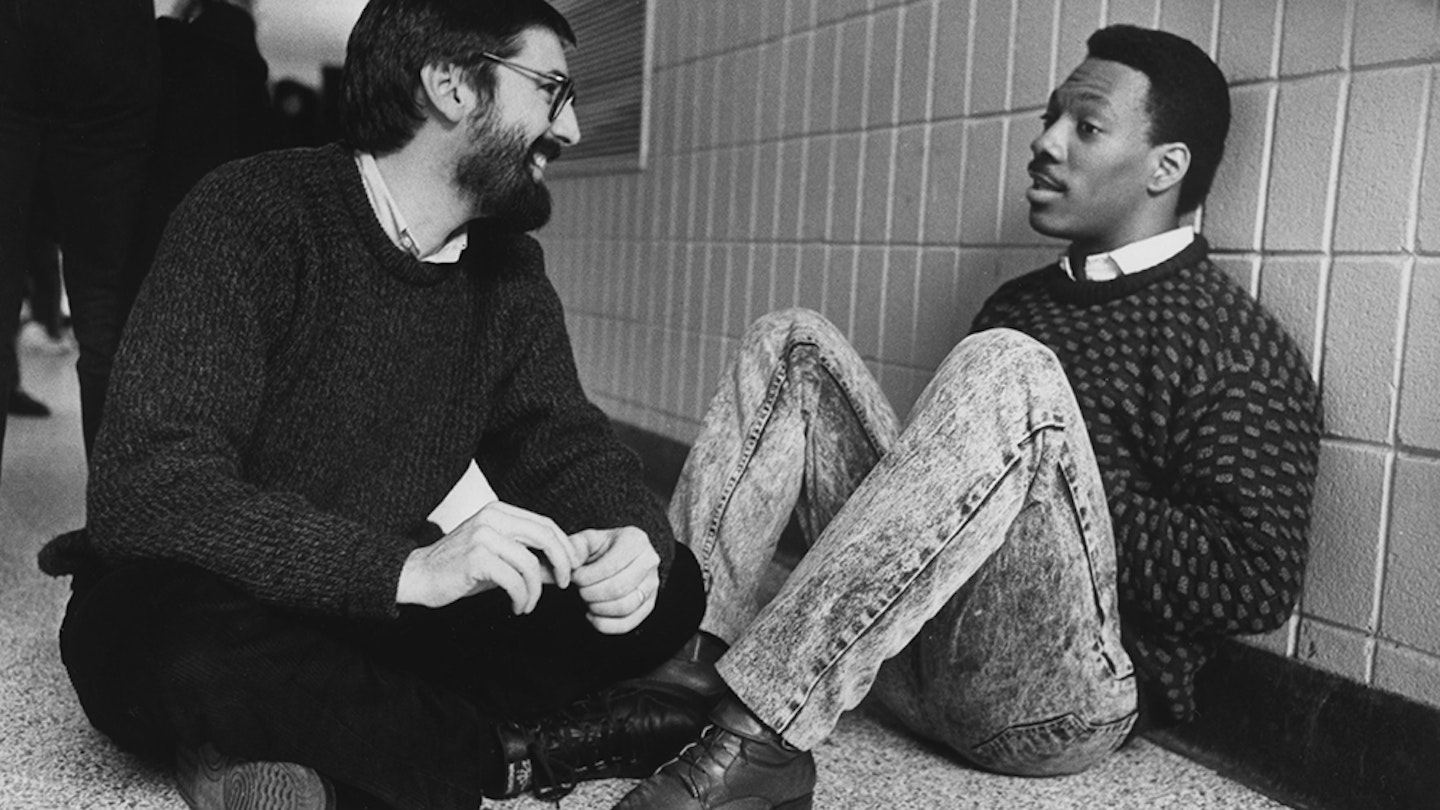

The 30-year-old Landis was coming off a hot picture and was perceived as something of a comic messiah. At the end of the 70s, this was of vital importance to the studios, who’d watched a whole generation of potential new stars, the Saturday Night Live performers become the hottest things on TV, only to transfer poorly to the big screen. So when wunderkind Landis and Aykroyd came up with a script based on characters which Aykroyd and Belushi had originally created and featured most successfully on the TV show, Universal’s Ned Tanen had little choice but to green-light the unusually big-budgeted rock’n’roll comedy.

He soon came to regret the decision. Landis, though undoubtedly gifted at comedy, proved an indulgent director, inclined to choose the over-the-top option every time and pushing the picture way over both budget and schedule. Belushi’s drug consumption, too, was at an all-time-high — no pun intended — and was adversely affecting his performance.

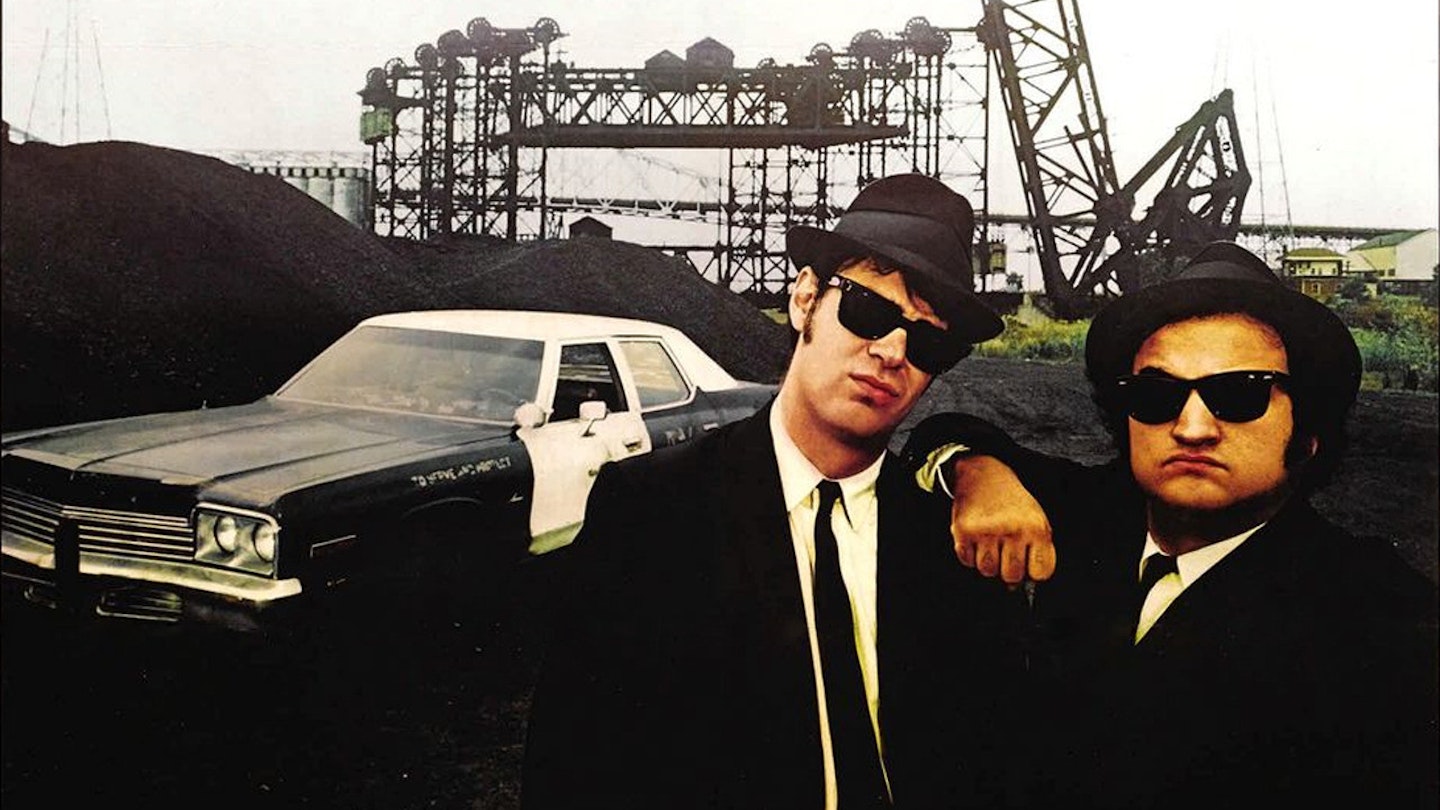

From such circumstances are cults created. Landis’ instincts proved correct: The Blues Brothers, when it eventually opened, hit just the right nerve with its target audience of ageing hippies and young punks, serving as a kind of counterculture rebel-yell against the rising tide of late-70s conformity. It was a “style” picture before such things became widespread, the style being an amalgam of urban sleaze, automobile crunch and blackheart rhythm and blues, and the Brothers’ uniform of dark suits, hats and Ray-Ban Wayfarer sunglasses quickly came to symbolise a protest against the dandified disco aesthetic.

And then, of course, there was the music, better music than any film had had for many years. The original impetus for the Blues Brothers characters was Belushi and Aykroyd’s abiding love of rhythm and blues, and they packed the picture with as many of their heroes as possible: Aretha storming through Think, Cab Calloway cruising through Minnie The Moocher one more time, John Lee Hooker boogying through Boom Boom in the street, Ray Charles demonstrating electric piano in an instrument shop, not to mention the hottest band since, well, since Booker T & The MG’s—which was hardly surprising since the likes of guitarist Steve Cropper and bassist “ Duck” Dunn were part of the original MG’s who served as the Stax house band on countless soul hits of the 60s. One of the more agreeable effects of the picture was that, as well as rehabilitating the then-unfashionable Ray-Bans, it also revived the careers of virtually all the musicians who appeared in it.

The plot barely deserves the epithet “basic.” The quest is portrayed through a series of set-pieces either musical or slapstick. The latter pitches the Brothers against the forces of darkness: the spectacularly badly-dressed John Candy’s enormous posse of traffic cops, a bunch of Illinois Nazis led by a saturnine Henry Gibson, a redneck country and western outfit and Jake’s estranged wife (Carrie Fisher).

These are the hyperbolically polarised forces of good and evil—hipsters and tightasses—with Belushi and Aykroyd playing the former almost as an updated Hope and Crosby reinterpreted via the Three Stooges. Certainly, there had never been as excessive a use of wanton slapstick violence in the movies before, albeit primarily aimed at automobiles. In one of the earliest set-pieces, the Brothers’ Bluesmobile is chased through a shopping mall by a posse of police cars, to the accompaniment of thousands of dollars’ worth of shattered plate glass; later on, several dozen more cop cars are run down embankments, piled up in streets and generally treated with violent disdain. It’s hardly surprising, really, that the film racked up such an enormous budget.