In July of 1974, Mel Brooks sat in the screening room at Warner Bros anxiously watching the assembled executives who were about to view his recently completed Western spoof, Blazing Saddles. He was desperately in need of a hit. His debut movie, The Producers, had been a minor success despite being decried by some critics as "too Jewish" and "over manic", but his follow-up, The Twelve Chairs, had been an unmitigated flop.

Ninety or so minutes of glacial silence later, after the blank-faced bigwigs had exited the screening room, Brooks reasoned that he was in big trouble. The critical response on the film's release was hardly more encouraging. "What I found amazing was that, in one of our better theatres, a civilised-looking audience laughed loudest and longest at a scene in which a bunch of cowboys sit around a campfire eating beans," declared a horrified John Simon. "One after another, they raise their backsides a bit and break wind, each a bit louder than his predecessor. If this is what makes audiences happiest, all future for the cinema is gone with the wind." (All fart gags in Simonís view being equal, but some apparently more equal than others).

Of course, it was exactly what delighted audiences. Brooks' wholehearted embracing of rank vulgarity, together with his innovative quickfire sketch structure, titillated crowds more used to sophisticated Hollywood humour and, with its sheer quantity of gags, left them breathless; if one zinger misfired, there was sure to be another mere seconds away.

But there's more to Saddles than an object lesson in the comedic possibilities of intestinal gas. As the more perceptive critic Kenneth Tynan, himself no stranger to the expert employment of vulgarity, remarked, Blazing Saddles is "low comedy in which the custard pies are disguised hand-grenades".

Uniquely for a spoof, and certainly unique in Mel Brook's oeuvre, it has a darkly angry heart. It is a film about real bigotry, a phony West and the unreliability of movies as repositories for a shared history. "The official movie portrait of the West is simply a lie. I figured my career was finished anyway, so I wrote berserk, heartfelt stuff about white corruption and racism and Bible-thumping bigotry."

It's hardly surprising that, as a Jew, Brooks felt the Western to be an alienating genre. In an industry with a high percentage of Jewish people, from screenwriters to execs to studio owners, the Western was unique in allowing no place for the wit or sensibility that had helped define the industry, let alone for Jewish characters. Equally it grievously misrepresented the role of black people in the culture of the Old West, with the 9,000 black ranchworkers, cattle-hands and cowboys thoroughly invisible in the classics of the genre.

It was hardly surprising, then, that, from the film's very first joke, Brooks lays his cards on the table. A bunch of redneck gangmasters demand that the black workers engage in "a good old nigger worksong"; the assembled grafters respond with an incongruously sophisticated rendition of Cole Porter's classic, I Get No Kick From Champagne, while the potato heads wind up singing Camptown Races. It's a nifty and very funny reversal, but Brooks can't help following it up with a gag in which our black hero winds up neck-deep in sinking sand.

It's this scattershot juxtaposition of heartfelt, angry satire with dumbass slapstick, all seasoned with a fair measure of vulgarity, that gives Blazing Saddles a tone unique to film - a tone shared by the most successful comedy magazine of the times. It is, quite literally, political correctness gone Mad.

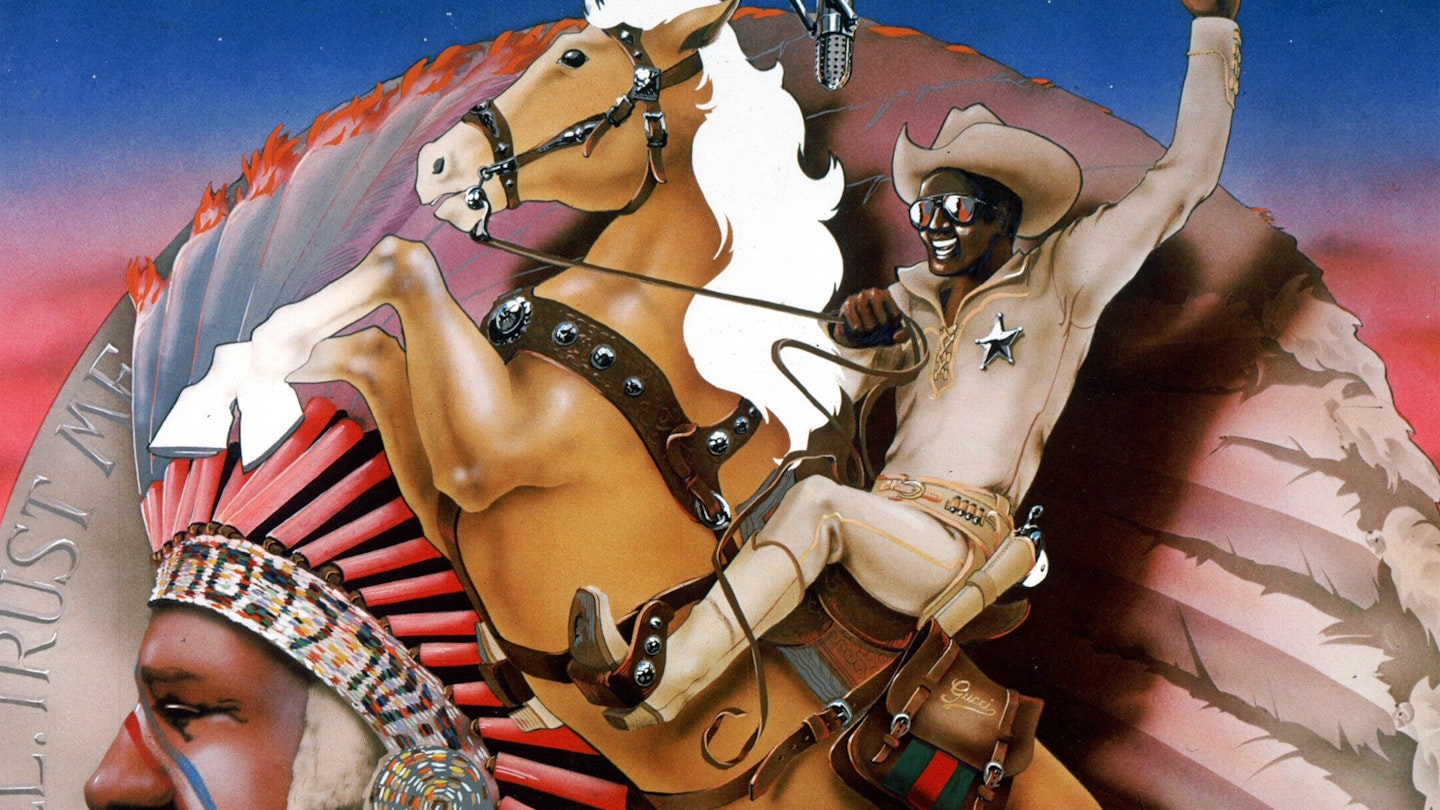

But if the bulk of the characters are bigoted or dumb or both, the movie is given its much-needed humanity by Gene Wilder and Cleavon Little as The Waco Kid and Sheriff Bart respectively. Wilder's career never flourished again as it did under Brooks' direction, and Little delivers an irresistible laid-back charm as a man who has to cope with little old ladies shouting, "Up yours, nigger!" at him.

Towards the end of the movie, Brooks' disciplined indiscipline runs out of control. But he manages to pull it back together and flick a final defiant "V" at the phoniness of the Western genre when, in the final shot of our heroes riding into the sunset, they suddenly dismount and climb into a limousine.

Everything about the romantic Western is a lie, it seems, including the happy ending. As Brooks said, he just wanted to "use every Western cliché in the book and perhaps, if we were lucky, kill some of them in the process". For him, it seemed to be personal, and perhaps it's for that reason he would never make anything as funny again.