"I think some — a lot— of people enjoy it, and that's their prerogative," a grumpy Harrison Ford told the Boston Globe in 1991. "I played a detective who did no detecting. There was nothing for me to do but stand around and give some focus to Ridley's sets." Ah well, he didn't much enjoy being in Star Wars either, and some — a lot — of people enjoyed that, too. The truth is, few actors come off well in sci-fi movies if they feel that it's them versus the sets or them versus the director's imagination. As it is, Harrison Ford's apparent bemusement works perfectly within Ridley Scott's framework; his former blade runner Rick Deckard, though expert at "retiring" the almost-human androids known as replicants, spends most of the film bemused.

As he tracks down four escaped replicants (a detective doing "no detecting"?) in a darkly malevolent, incongrously rainy 2019 Los Angeles, he falls in love with femme fatale Rachel (Young), who is a replicant. And it's this tentative, enigmatic relationship that drives the film.

Blade Runner is possibly the most talked-about sci-fi movie ever made. It achieved this honour by being a failure on its original release, thus attaining the valuable sheen of a true cult (something that could never be said about Star Wars, despite the rapacity of its followers). When re-released theatrically in the form of a Director's Cut in 1992, it was reappraised by formerly sniffy critics, and more people paid to see it. The irony of this belated legitimisation is that the Director's Cut is more cryptic and ambiguous than the original, and — crucially to the sort of fan who roams the Internet — supported the popular theory that Deckard himself is a replicant.

There are actually only minor differences between the original and the Director's Cut (indeed, the tag is misleading, as it's actually a compromise between director and studio). Scott removed the explanatory voice-over and happy ending, both of which had been added after disastrous sneak previews. He also introduced a 12-second dream sequence involving a unicorn, which helps explain the significance of an origami unicorn that appears in the final sequence. Oddly, some of the extra frames of violence in the video version are now excised. While obsessive aficionados hotly debate the merits of each version (and whether Deckard is a replicant or not), the casual fan will glean enough pleasure just watching the film — any bloody version — and admiring its astonishing production values.

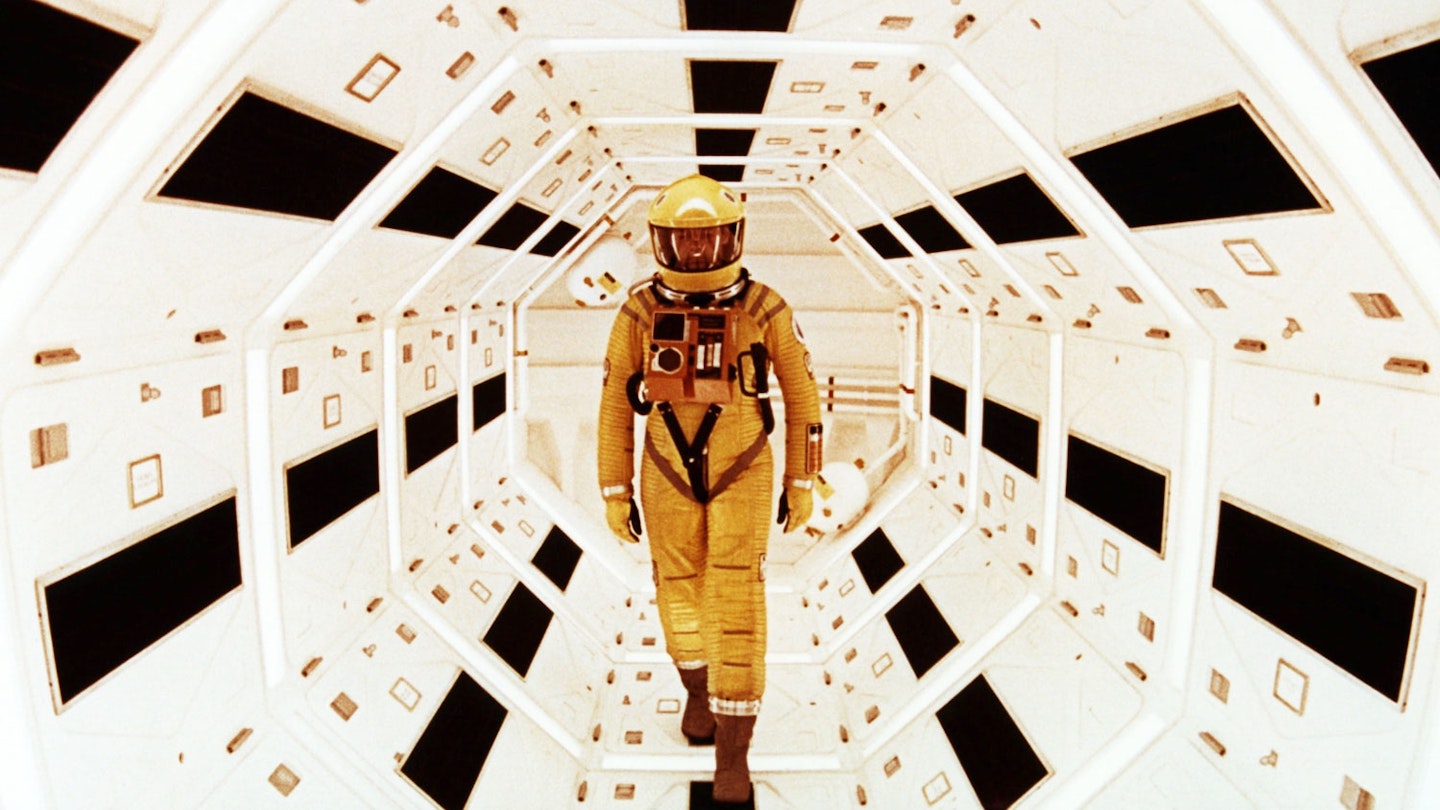

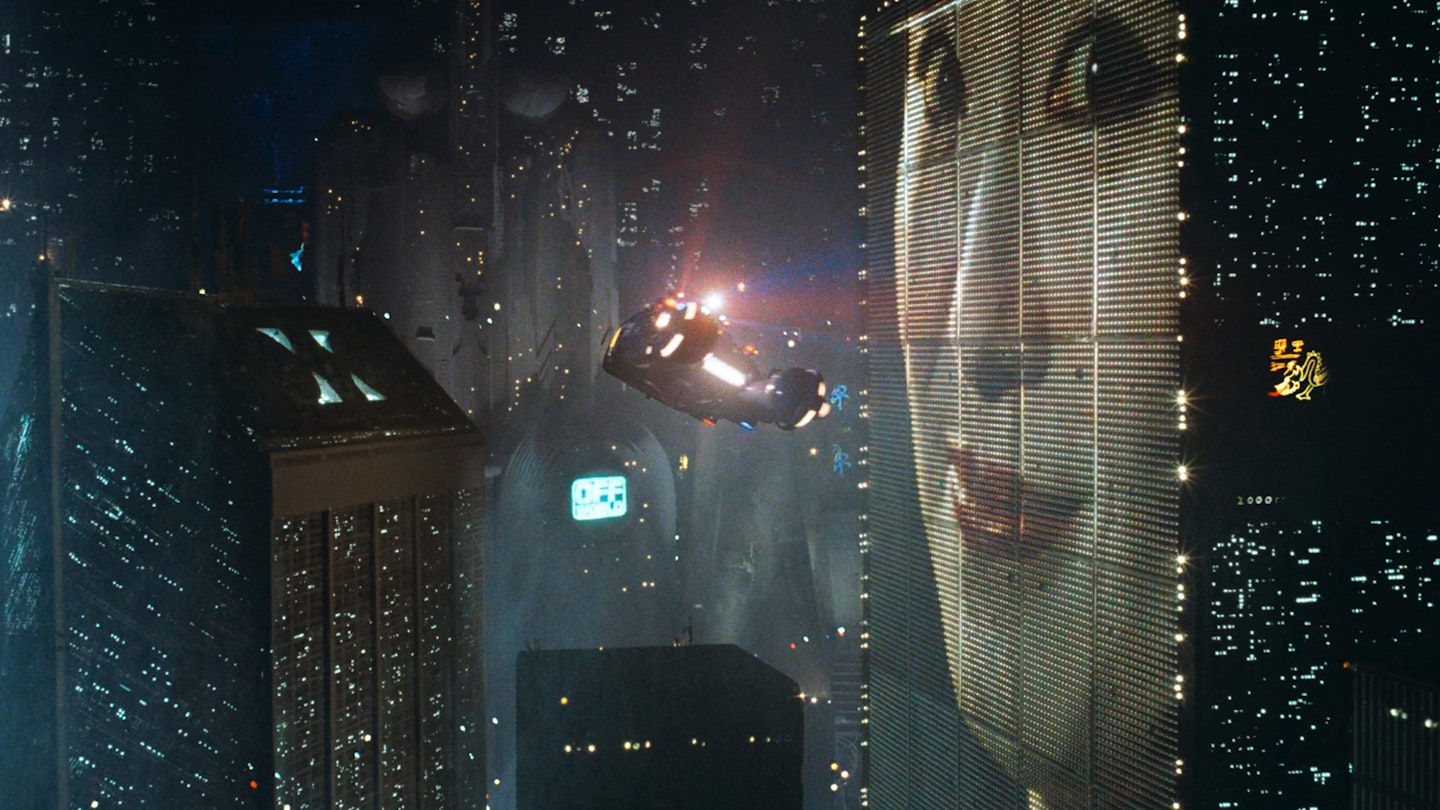

Scott's advertising background has, however, given him a unique sixth sense for overdoing it, hence the dusty light shafting through Venetian blinds; the pounding, backlit rain; and the kaleidoscopic colours, now the basic grammar of any filmmaker. The look of Blade Runner can be credited to production designer Lawrence G. Paull, "visual futurist" Syd Mead, art director David L. Snyder, cinematographer Jordan Cronenweth and ubiquitous FX man Douglas Trumbull. But the overall vision was Scott's: "a film set 40 years hence, made in the style of 40 years ago." (Note, by the way, how much warmer its pre-CGI effects are than those which dominate today.)

In H.G. Wells The Time Machine, Earth was divided into a clean, Aryan paradise above ground and a hellish, primitive netherworld beneath, a division that recurs constantly in movie sci-fi. In Blade Runner, the sleek and the ugly, the ancient and the modern, co-exist, just as they do in any big city today (the Ancient Egyptian grandeur of the Tyrell Corporation versus the dilapidated, leaky hulk of J.E Sebastian's building). Perhaps this is why Blade Runner's future is so compelling, and why it's still duplicated ad nauseum in rock videos and bank adverts.

But Blade Runner is more than a collection of stunning pictures. It oozes the type of allegory that will keep stoners up all night for years to come. Try this one for size: Batty (Hauer) is Jesus — after all, he sticks a nail through his hand and dies, releasing a dove as he does so — and Tyrell (Joe Turkel), referred to by Batty as his "maker", is God. This theory makes the replicants us. Well, humans are programmed, like replicants, to die from birth, a paradox encapsulated in the last line of the film: "It's too bad she won't live! But then again, who does?" Stick that in your bong and smoke it.

Oh, and Deckard is a replicant, and the Director's Cut isn't as good.