There is something clod-hopping about the name Blade Runner: The Final Cut. What does that absurdly clumsy subtitle imply we’ve been watching for the past 25 years: a rough assemblage? A two-hour trailer? Taken in conjunction with 1992’s ‘Director’s Cut’, has this been the movie world’s longest work-in-progress? With industry wags referring to “today’s cut of Ridley Scott’s science-fiction masterpiece”, perhaps the subtitle is intended as a promise rather than a recommendation - that this really will be the last time

we’re asked to shell out to enter the dystopian nightmare of Los Angeles in 2019.

It is, of course, the only clumsy thing about the film, which really

is a genuine masterpiece worth shelling out for again and again. One of Scott’s great strengths as a filmmaker is his impeccable sense of taste, and that, it seems, extends to his subsequent treatment of his films. The Final Cut is not an excuse for the pointless and indulgent reintroduction of deservedly binned scenes (see Coppola’s Apocalypse Now: Redux), or ex post facto fiddle-faddling (Spielberg’s timid removal of the guns in E. T.). In fact, this latest incarnation is better thought of as a meticulous and loving restoration rather than a new cut, with Scott carefully polishing, burnishing and primping up his finest film. After all, there really isn’t much to fix.

The changes the director has made are pretty minor, and so skilfully integrated into the print that you find yourself questioning whether moments you have in fact seen half a dozen times before are new additions. Most are in the form of tidying up, purging the irritants that have had Scott wincing for the past quarter of a century. Police chief M. Emmet Walsh has been conjured from the grave in order to correct himself and announce that there are four ‘skin-jobs’ on the loose, not five. When Zhora (Joanna Cassidy) is gunned down by Deckard (Harrison Ford) and sent flying through multiple plate-glass windows wearing not much more than a see-through PVC macintosh (surely one of the greatest amalgamations of sex and violence in cinema history), digital technology ensures that this time round she does not put on five stone, grow a couple of feet taller and transform into a lumbering stuntman.

More of interest to anyone other than continuity nerds, Scott beefs up the violence in Batty’s killing of his maker, Tyrell, the audience being treated to, if not lingering on, extended shots of Rutger Hauer’s thumbs plunging into the hapless industrialist’s eye-sockets. What might seem an excuse for some audience titillation, or a concession to the intervening 25 years during which screen violence has become ever more graphic, actually improves both this scene and the subsequent ones. That’s because Blade Runner is a film all about eyes: the film begins with a brief shot of one; it’s the peepers that give away the replicants’ true nature (the only change that Scott has made that is less than happy is the conceit of having the replicants’ eyes randomly reflect and flare - it renders the Voight-Kampff test redundant); and in Batty’s death speech they are the organs through which he sees his famous “attack-ships on fire” and “C-beams glitter”. The added emphasis on Batty’s point of attack surely not-coincidentally reinforces the film’s Oedipal echoes.

But it’s actually the passing of time that’s wrought more changes on the movie than Scott’s loving tinkering. All movies date, and science-fiction movies are inevitably more prone to the signs of ageing than any other genre. The innovations that filmmakers imagine stubbornly don’t, in fact, transpire (flying cars), while unheard-of inventions become everyday (mobile phones). Deckard’s zooming in on details of a photograph was an unthinkable leap of technological imagination in 1982, but now it looks like he’s working on an early shareware version of Photoshop. Meanwhile, the luminous green displays and clunky keyboards - apparently there are no mice in the future - look suspiciously like they’ve been cannibalised from a job-lot of BBC Acorns. Presumably Scott could have digitally ripped them out and installed replacements, but those too would inevitably date. Instead he sticks with the originals, giving the film a rich, Gilliamesque feel, in which old technology rubs shoulders with the new.

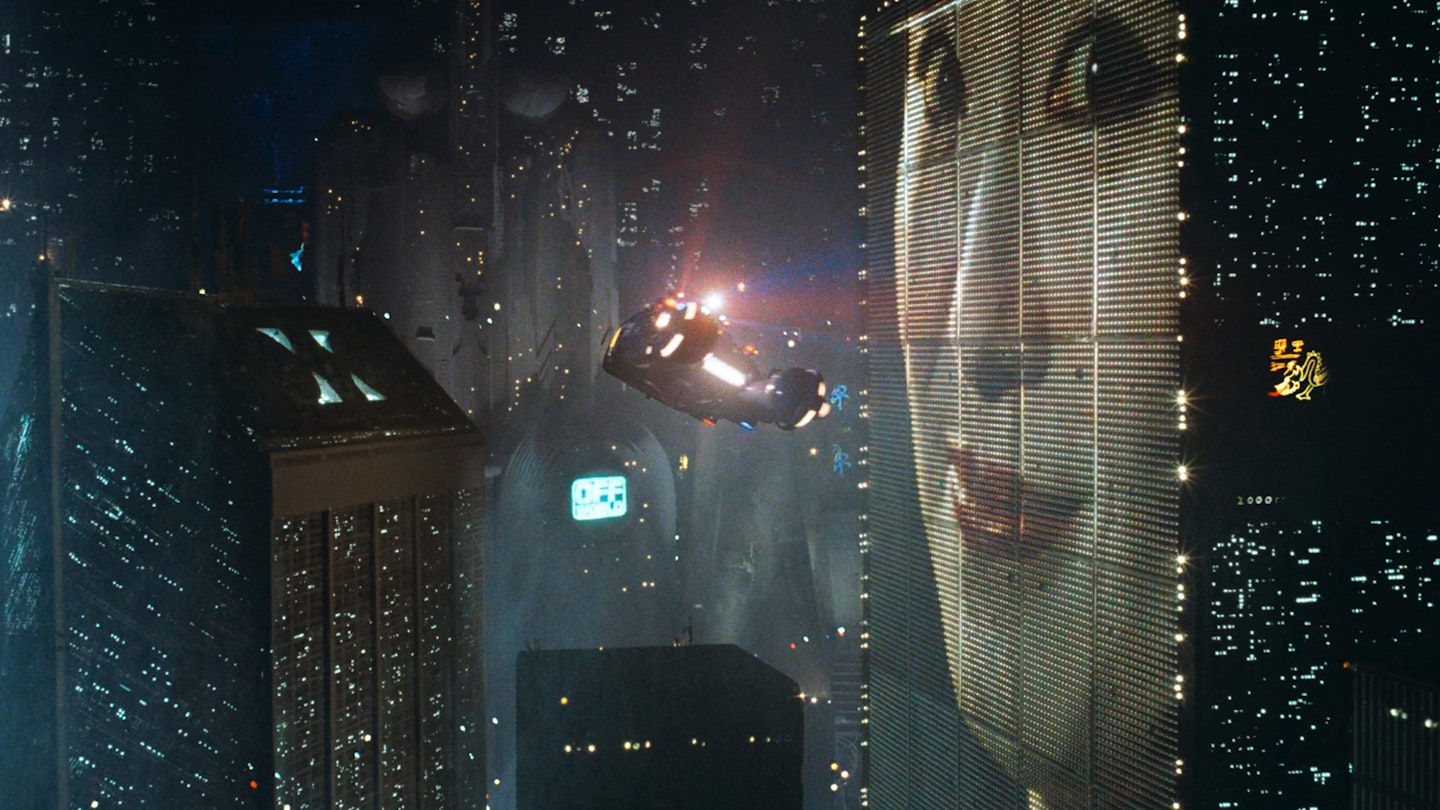

No, the real change, and the best reason to seek out The Final Cut on the biggest screen you can find, is the near miraculously improved quality of the print. Scanned frame by frame at ultra-high resolutions (it was rendered at 8,000 lines a frame - four times as dense as many other restorations, according to the distributors), the film looks utterly stunning. From Scott and ‘visual futurist’ Syd Mead’s tiny details, such as the funky novelty umbrellas with their neon stems, to jaw-dropping vistas like the opening, fire-belching cityscape, it remains an unparalleled visual achievement.