Thousands of murders go unsolved; most are forgotten, why do some obsess us so? Google ‘Jack the Ripper’ and you get nearly 6 million results. Type in ‘the Black Dahlia’ and you get twice as many. Like the case of the Ripper — a longtime favourite of filmmakers and speculative novelists — the case has all the ingredients of an enduring mystery. As with the Ripper there’s a sense of the crime somehow crystallising a certain moment; the foggy London of Saucy Jack was on the cusp of modernity, at least in media terms, with news sheets reporting every ghastly detail to a guiltily entertained public.

As for Elizabeth Short, who would, though she would never know it, become known to generations as The Black Dahlia, her grisly murder in 1947 — she was found beaten, buggered and bisected — happened against the backgrounds of the golden age of cop movies and the Hollywoodland sign. With false leads, hoax confessions, leaked tidbits to a hungry press and allegations of corruption, the case had the air of a noir from the start.

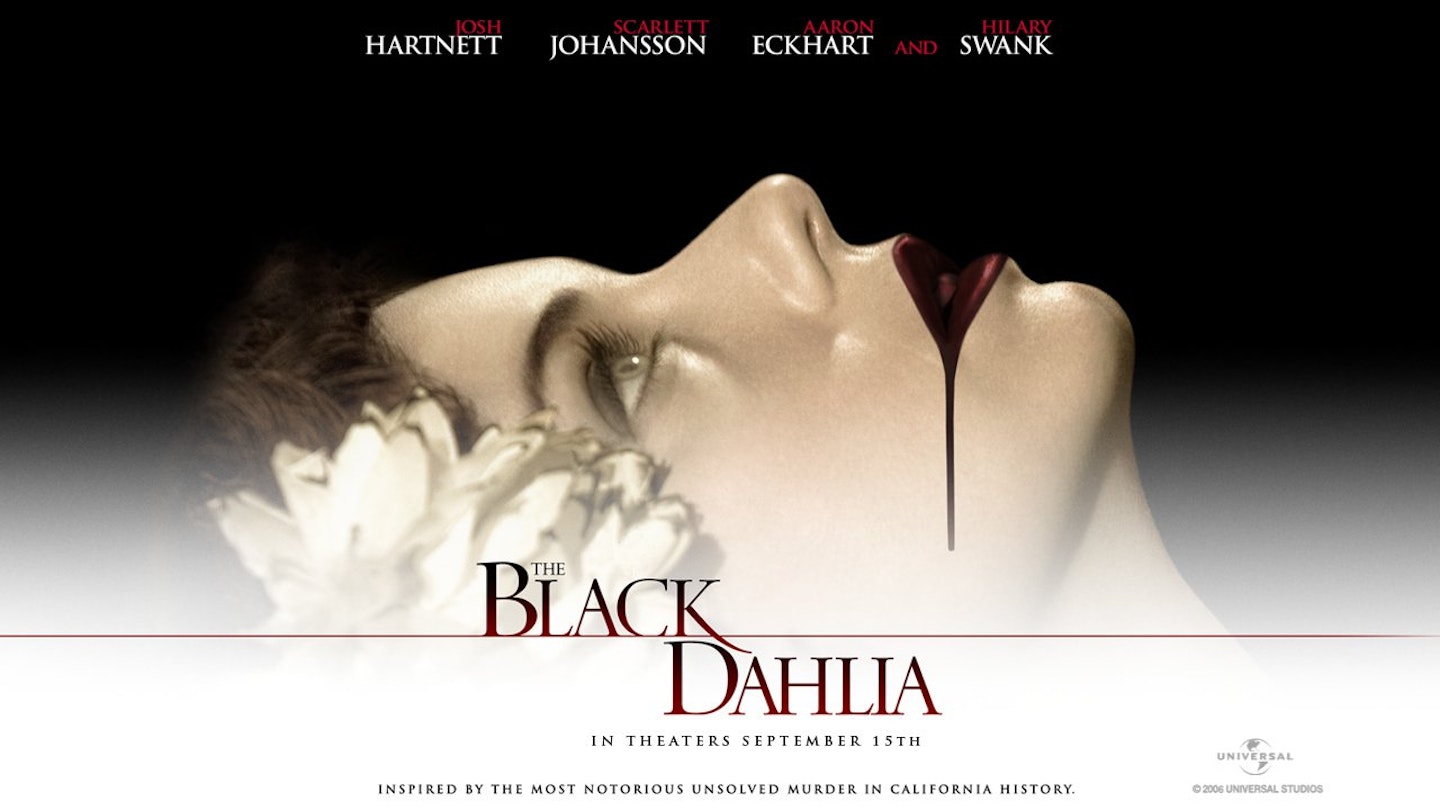

And so to Brian De Palma’s adaptation of James Ellroy’s The Black Dahlia. De Palma has been toying with film noir as far back as Obsession and as recently as his criminally ignored Femme Fatale, though for most the obvious comparison will be Curtis Hanson’s L.A. Confidential. But while L.A. Confidential was a straightforward period policier, typically for its director The Black Dahlia is something much more, and in an odd way much less. It’s sated in De Palma’s trademarks: there are films within films; a gimlet eye for the pornographically sleazy and elements of mistaken identity. And then there is the exuberant technical bravura. An extended crane shot manages to bolt a spectacular gunfight to the murder itself, mischievously hiding it in the background; there’s a stunning fall through a spiral staircase that manages to reference both his beloved Hitchcock and, cheekily, his own Scarface.

And his casting is right on the nose. Josh Hartnett is startlingly effective as the bewildered, fundamentally decent detective, a man so stolidly gumshoe that he puts his hat back on immediately after sex. Aaron Eckhart fulminates as his bitter, secretive partner while Scarlett Johansson is transformed into a rouge-lipped femme fatale while long-time collaborator Dante Ferretti and veteran lenser Vilmos Szigmond create a lush, moody atmosphere that seems to locate the film permanently on the verge of dream; everyone smokes furiously bathing the movie in a kind of golden fug.

But along with De Palma’s undoubted strengths come the familiar problems: like the little boy pulling apart a spider to see how it works there’s a coldness, an emotional immaturity. De Palma is interested not a jot in the feelings of his characters, and thus the denouement which, in a way appropriate for noir, verges on the loopy, is frigid and unsatisfying. It’s par for the course for the director, but here it’s a flaw thrown into sharp relief by the reality of the subject matter. Perhaps we should try to disentangle poor Elizabeth Short from the fiction and recall that that at the centre of this maelstrom of technical artistry, armchair speculation and noirish atmos, there’s the ruined body of a young woman who, 59 years ago, met someone, or something, that surely no-one deserves to.