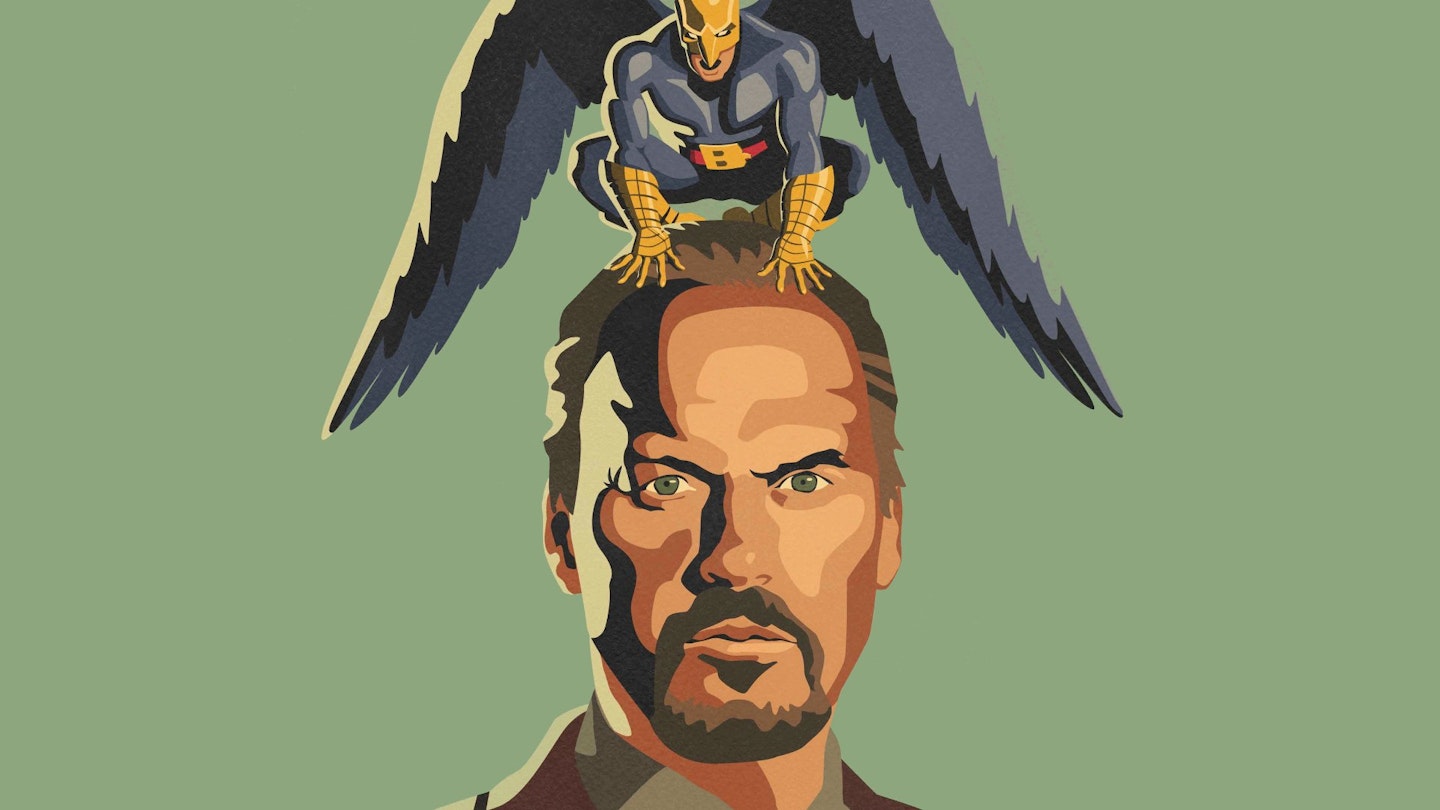

At one point during Birdman, Michael Keaton’s Riggan Thomson, a former movie star-turned-wannabe artist, deludes himself that he is his superhero persona, Birdman, skimming through the skyscrapers of New York at a dizzying speed. It’s an image that could stand for the film itself: untethered, a feel for the slightly ridiculous, completely exhilarating. Escaping the heavy gloom of 21 Grams, Babel and Biutiful, Alejandro González Iñárritu (credited here as Alejandro G. Iñárritu) has conjured up something that takes on board Huge Issues — sanity, narcissism, parenthood, marriage, creative integrity, artistic legacy — but with a directness and lightness rarely present in his back catalogue.

It could be termed this year’s Gravity, and not because they share a Mexican director and DP Emmanuel Lubezki. Like Cuarón’s film, Birdman soars on a purely cinematic imagination, defying formula, expressing ideas in completely visual ways. As an exercise in pure technique, it is daring, exacting and will leave you head-scratching in a how-did-they-pull-that-off? way. But the form always serves the substance.

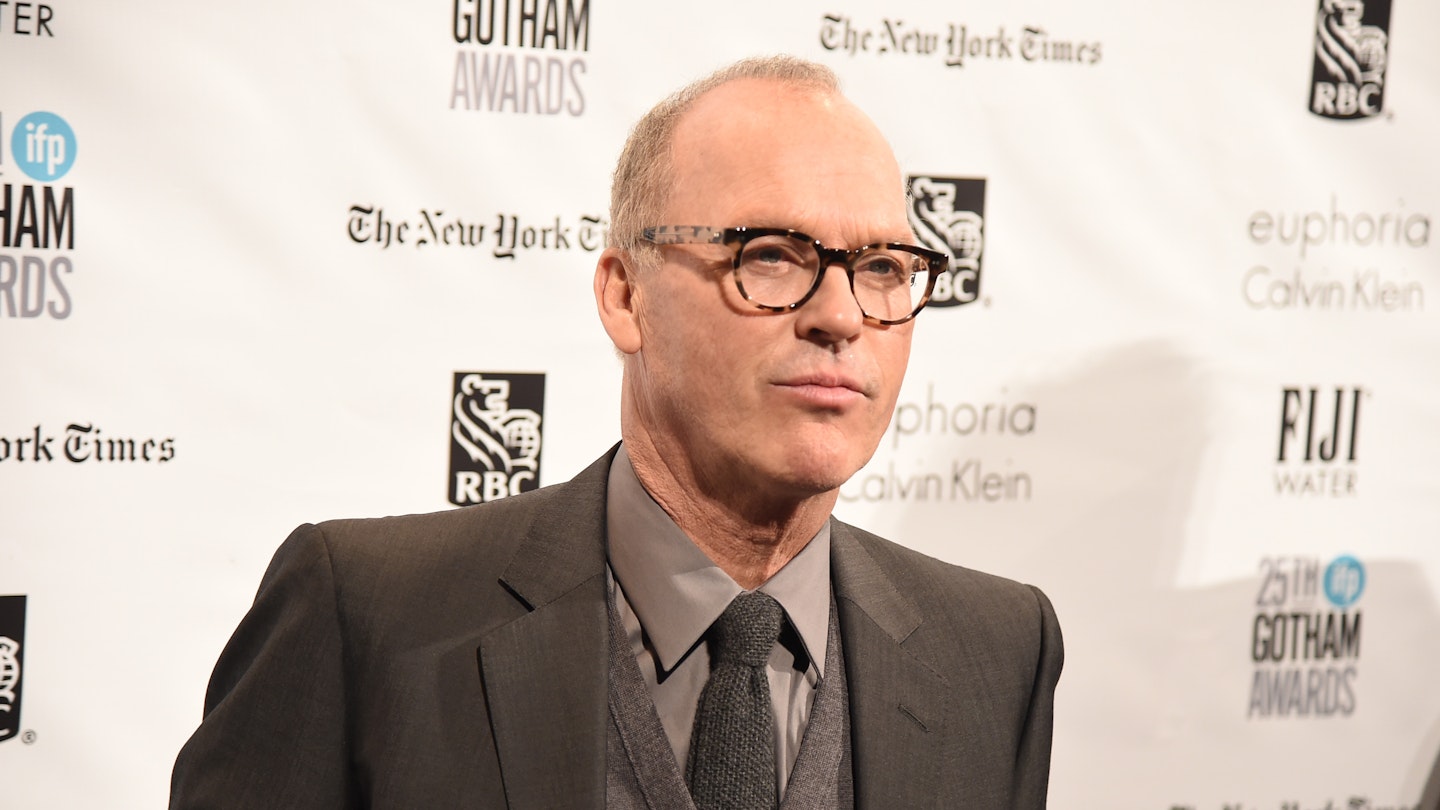

A compelling portrait of artistic angst and existential collapse, it starts as a black comedy of theatrical hubris but slowly morphs into something more affecting and poignant. It’s a tour de force not only from Michael Keaton but everyone involved, and awards will surely follow. But this is a film that neither covets or needs gongs. It is spectacularly unclassifiable.

For all its superhero accoutrements, Birdman, on the outside at least, is a let’s-put-on-a-play-right-here farce. Faded movie star Thomson has staked the last of his superhero savings on writing, directing and starring in a Broadway adaptation of Raymond Carver’s What We Talk About When We Talk About Love in a last-ditch attempt to claw back a shard of artistic integrity. Iñárritu and writers Nicolás Giacobone, Alexander Dinelaris and Armando Bo pile on every backstage drama you can think of: there are more than enough accidents (minor and tragic), secret liaisons, creative disputes and unwanted erections to power a dozen Noises Offs. But these aren’t toothless hijinks. There are pointed stabs at needy stage types, imperious New York critics (Lindsay Duncan briefly but memorably sketches an icy reviewer waiting to kill Riggan’s play in a heartbeat) and contemporary theatre’s reliance on movie stars to pull in the punters. Other cultural touchstones don’t get off scot-free either — there are jabs at the highbrow (French theorist Roland Barthes), the populist (Justin Bieber) and the likes of Michael Fassbender, Robert Downey Jr. and Jeremy Renner for donning cowls for cash. Edward Norton’s Hulk is given a pass. Not even Birdman is that meta.

At the eye of the drama is Keaton’s Thomson undergoing the mother of all meltdowns, the opening image of a dying star a pre-emptive suggestion that Riggan’s interior crisis may be happening at a cosmic level. In our first glimpse of the actor, he is levitating in his dressing room, his mind so out of whack that he is convinced he has telekinetic powers, verbally wrestling with Birdman (Keaton in a Christian Bale-esque lower register), who constantly taunts him that he craves public adulation. If the film gets a frisson from the career parallels between Riggan and Keaton — Riggan did one more Birdman that Keaton did Batman — the actor gives it so much more, treading a tightrope between self-doubt and narcissism as he slowly reveals an actor’s fracturing psyche before our eyes. This isn’t stunt casting. This is a great actor on the form of his life pitching a flawed human being and a monstrous alter-ego and making you connect with both.

If it were built around Keaton alone, Birdman would be strong enough, but Iñárritu draws a clutch of stellar turns from Andrea Riseborough (as the leading lady Thomson may or may not have got pregnant), Zach Galifianakis (in subtle, restrained mode as Thomson’s loyal producer) and Amy Ryan (as Thomson’s estranged wife, a voice of calm reason in a topsy-turvy world). But two supporting performances stand out. Emma Stone is raw and real as Riggan’s daughter-turned-PA, fresh out of rehab, keen to explain to her old man the importance of Facebook “likes” to stop him becoming a dinosaur. But, best of the bunch, is Edward Norton’s Mike Shiner, an arrogant creep of a movie actor called in at the last moment to help boost ticket sales. Be it unnerving Riggan by memorising his lines prior to first rehearsal or drinking real gin instead of water on stage or hitting on his co-star (Naomi Watts), Norton (a Method actor playing a Method actor) does for Birdman what Ben Affleck did for Shakespeare In Love — gives it a swift kick up the arse. When he temporarily moves out of the spotlight towards the end, the film misses him, but not before a couple of quiet balcony scenes with Stone that are among the most memorable in the picture.

Happily, for a film about the theatre, Birdman isn’t the slightest bit stagey. Lubezki’s work here makes that shot from Children Of Men feel like MTV, tricking us into believing the movie is unfurling in one long, sinuous take even though the action takes place over several weeks and in various locales. From the point where we see Riggan levitating in his dressing room, it is half an hour before there is another discernible cut. The level of artistry and planning is immense, but this isn’t empty gimmickry. Lubezki’s camera is alert and alive, following Keaton around so you feel at the centre of Riggan’s crucible. The long takes — seamlessly stitched together by editors Douglas Crise and Stephen Mirrione — also inform the film’s dialogue between stage and screen acting: while the actors are clearly acting for a camera, the duration of shot gives the performances the sustained intensity of theatre, the best of both worlds. Iñárritu also isn’t above throwing a little gag into the mix. The score, by Antonio Sanchez, is a percussive jazz effort that seemingly propels Lubezki’s camera along, but at one point the camera slyly reveals Sanchez playing the drums in a corner. Mel Brooks would be proud.

Interestingly, jazz drumming is the score of choice for another 2015 awards contender, Whiplash, but Whiplash never finds the cinematic fireworks that Iñárritu whips up here. This is filmmaking that’s at once planned to a tee but feels improvised, free-form. You can take the film’s full title, The Unexpected Virtue Of Ignorance, in many ways, be it on a first-base plot level — Riggan’s journey does degenerate towards a certain kind of success — or more broadly, that the creative process, stumbles, setbacks and all, can often be joyous. Yet it is hard not to take it on a broader level. Iñárritu, Lubezki et al tear up the rulebook, forget what they know and just play. The result is extraordinary.