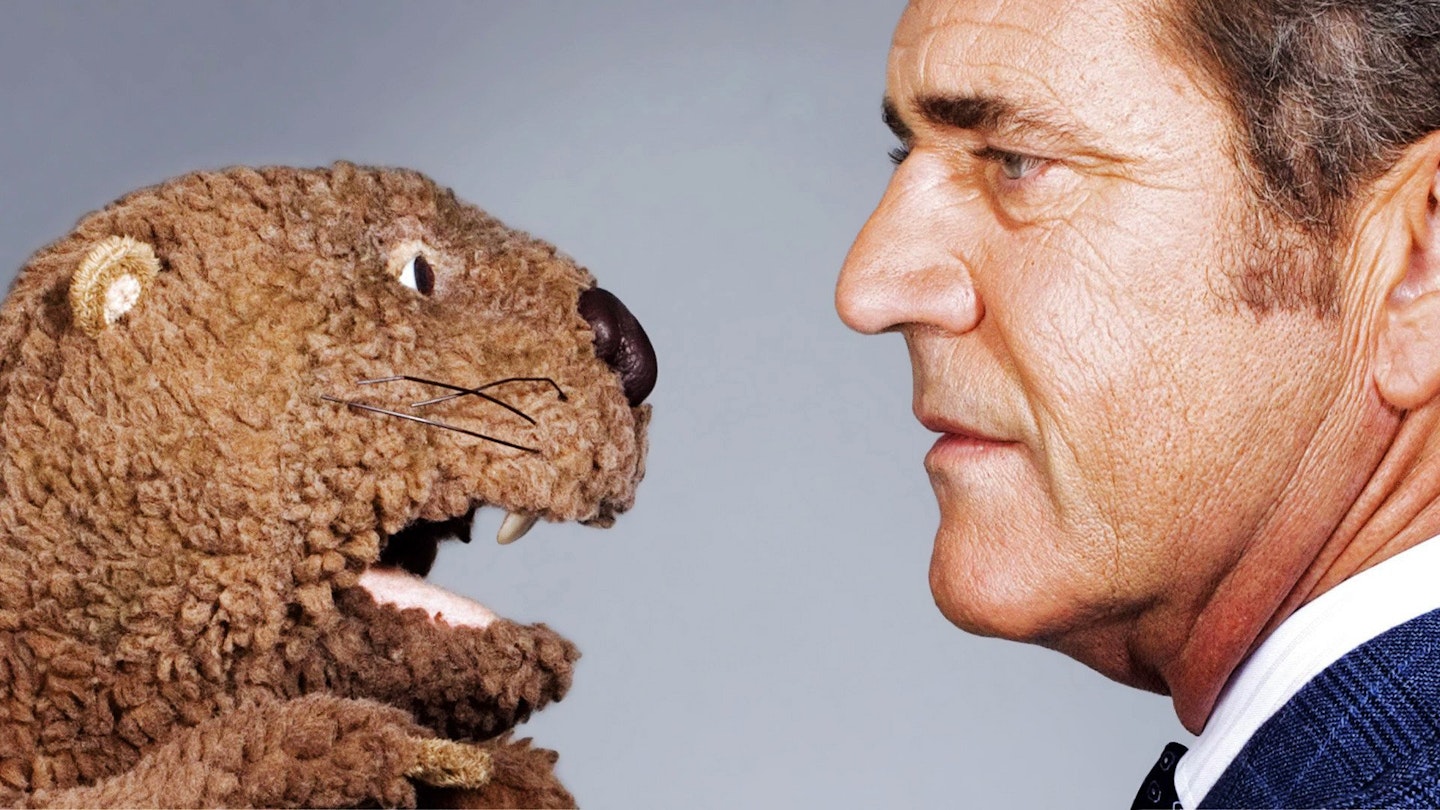

Amid all the high-octane lunacy of 2011’s summer season — aliens, robots, more aliens, pirates, even more aliens — the demented image to beat will be that of a ménage à trois between Mel Gibson, Jodie Foster and a furry beaver hand puppet. The threesome takes place midway through The Beaver, by which point you will have become acclimatised to seeing Gibson manipulating the puppet on his hand, not to mention making it speak in gruff, Cockney tones reminiscent of his Edge Of Darkness co-star Ray Winstone. The Beaver is not what you might expect — a silly comedy designed to rebuild Gibson’s image.

Instead, it’s a darkly funny psychodrama that deliberately draws on its star’s troubled past to intensify the action. The opening shot of Walter Black sees him sprawled across a lilo, arms extended to look eerily like Jesus on the cross. It’s soon clear that Walter is an alcoholic and deeply depressed. Gibson, with heavy bags under his eyes, staggers through the action as if crushed under the weight of his character’s ennui. It’s a phenomenal performance — if, indeed, you can call it acting.

The film as a whole is more problematic. There are several ways this story could have been played — as a wacky Jim Carrey vehicle (which, at one point in development, it was), say, or as a creature-feature horror where the puppet has a mind of its own. Foster, who both directs and plays Walter’s wife, swerves away from the fantastical and makes The Beaver, for the most part, a deadly serious treatise on mental illness. She and Gibson are the perfect people to make that movie — the two are long-time friends and it’s unlikely anyone else could have coaxed such a raw performance out of him — but the vérité mood makes it difficult to buy into the unlikelier elements of the story, such as Walter’s meteoric rise to fame (in a Hudsucker Proxy-esque sequence, everyone in America suddenly wants their own Beaver). The subplot between Walter’s bitter son (Anton Yelchin) and his high-school crush (Jennifer Lawrence) is well-acted but feels shoehorned in and unconvincing, especially the reveal that the cheerleader is secretly a Banksy-esque street artist.

Had Foster ditched the romance and whimsy, and played the story out solely through Walter’s tortured eyes, The Beaver could have been a batty rival to Black Swan. As it is, tonal inconsistency stops it short of being more than a fascinating oddity, with one great performance by Gibson and another by his wrist.