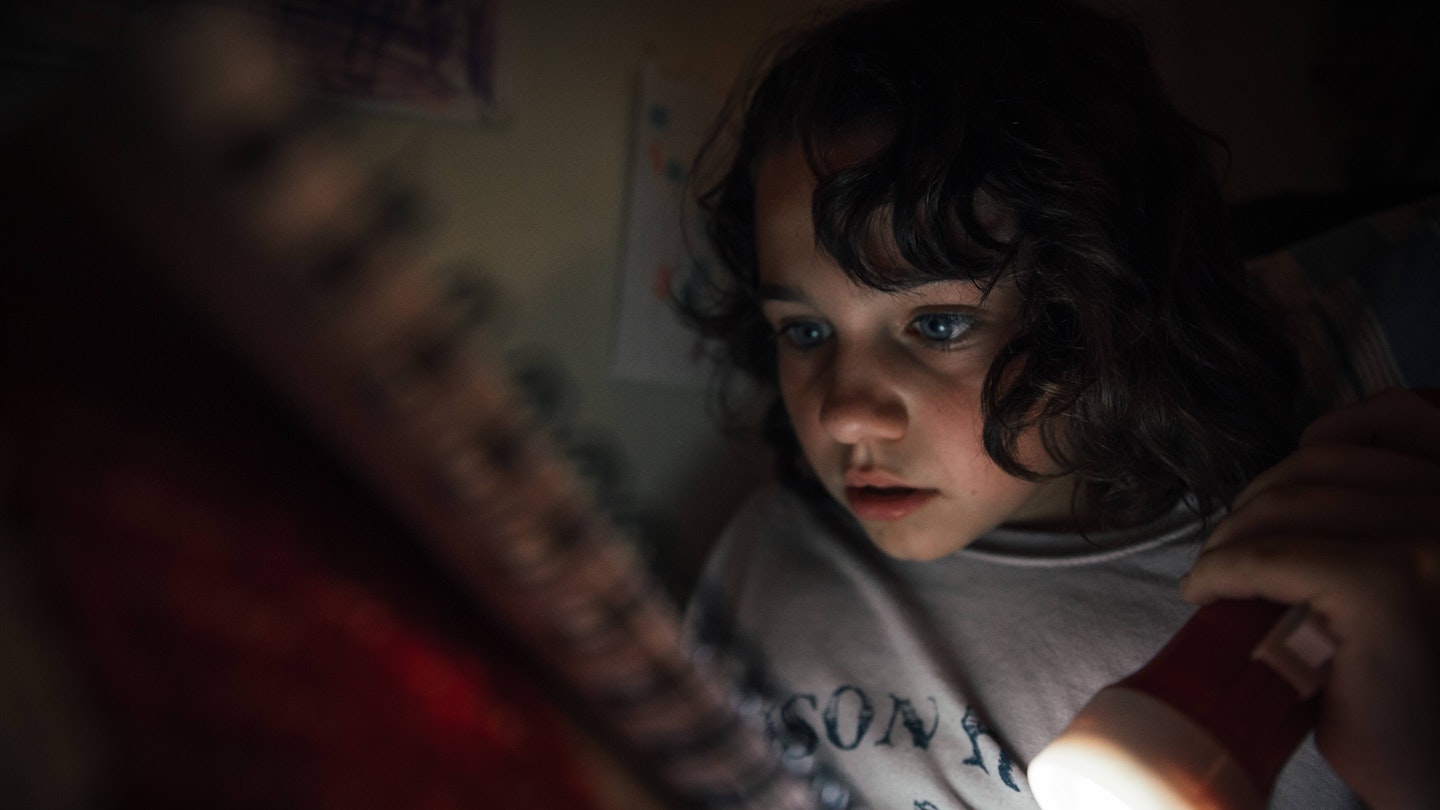

As its title suggests, Beasts Of The Southern Wild is no ordinary movie. It’s an eccentric, low-budget travelogue that, at times, beggars belief as its characters pass through its waterlogged swamplands. Anything goes in The Bathtub, and it usually does. The local pub has dispensed with licensing hours altogether and in the film’s most iconic scene, little Hushpuppy (Quvenzhané Wallis) runs through the town’s festival night with a Roman candle in each hand. The sets look like something out of Mad Max 2 but, despite its fantasy trimmings, this is a real story about a hidden but also very real world.

Though it doesn’t ape his meticulous style, director Terrence Malick is a touchstone here, since its fractured voiceover and opening, montage-like scenes of an anarchic rural idyll recall his 1978 film Days Of Heaven. But where Malick’s film saw a complicated story from a simple girl’s point of view, Beasts Of The Southern Wild shows a younger girl wrestling with her immediate circumstances in the aftermath of a devastating Katrina-like weather event. Though it never goes as far as patriotism, the theme here is roots, dealing with pride and community in the most abject circumstances. But while this is a world beyond poverty, it is way beyond misery too.

With great generosity, director Benh Zeitlin gives us two films for one. Hushpuppy is the focus, but the film deals with her father’s journey, too. Wink (Dwight Henry) believes in tough love, giving Hushpuppy the space to run wild. At first sight it seems he doesn’t care, but Wink cares very much. He wants Hushpuppy to take over in the event of his death, so he teaches her the skills she’ll need when he’s gone. This isn’t sentimental, Sting-saves-the-rainforest stuff, though. From her father, Hushpuppy inherits a ruthless militancy that, despite the eventual interference of do-good white liberals, literally prepares her for the end of the world.

Key to this are two astonishing performances by Wallis and Henry, two non-professionals drafted in from the metropolitan areas of New Orleans. Both sink effortlessly into roles that have no template, Henry being especially convincing as the unsentimental Wink, who tries to reassure Hushpuppy on the night of the storm by picking an angry fight with it, blasting his shotgun up into the torrential rain. Wallis, however, holds her own, showing no fear as the intrepid, shock-haired tomboy.

The parallel story involves Hushpuppy’s fears for the world, mirrored in her search for her missing mother, herself a strong woman whose face is obscured but whose presence is felt, long after her mysterious departure. This, too, is handled without sentiment — just another aspect of the heroine’s journey — and Zeitlin keeps things admirably vague, using the search as poetic device and not a literal quest that will pay off with a comfortable Hollywood coda. Does she ever meet her mother? That would be telling but, like other strands of this thoughtful tapestry, it’s something to be debated after the credits roll.

That’s because Beasts Of The Southern Wild isn’t simply a film about outlandish spectacle; it’s a film about survival in its purest form. Hushpuppy carries the weight of the world on her shoulders, believing it to be so badly broken that only she can fix it, a nightmare we see in the form of marauding aurochs — giant warthogs — that pursue her throughout the film. Can she outrun them? Tame them, even? That is Hushpuppy’s mission, but this is not a standard eco-doom movie, rather an empowerment story for the generation growing up in the shadow of Al Gore’s apocalypse.