Few, if any, filmmakers could hit a decade-long losing streak like Scorsese and still have us breathless with anticipation whenever a fresh project is announced, champing at the bit to see whether he's finally rediscovered the incandescent form of Taxi Driver, Raging Bull and GoodFellas - and whether his latest will be the picture that finally bags him an Academy Award. But, while The Aviator was his strongest Oscar bid since GoodFellas (it is, after all, a movie about Hollywood), it couldn't withstand comparisons with Scorsese's masterworks. It's a great story well told, but we expect more than good storytelling from the man who gave us Travis Bickle.

Scorsese excels at exploring characters in whom he feels a deep personal resonance, those who, like him, have done battle with their own demons. It's through misfits like Bickle, La Motta, Henry Hill and even The King Of Comedy's excruciating Rupert Pupkin that he's sought to dig out the truths of the human condition. But it's difficult to imagine the son of striving immigrants having much affinity with Howard Hughes who, despite his fascinating, tragic arc, wasn't even a self-made man, and who funded his outlandish endeavours by milking the inexhaustible cash cow of his family's machine tool business.

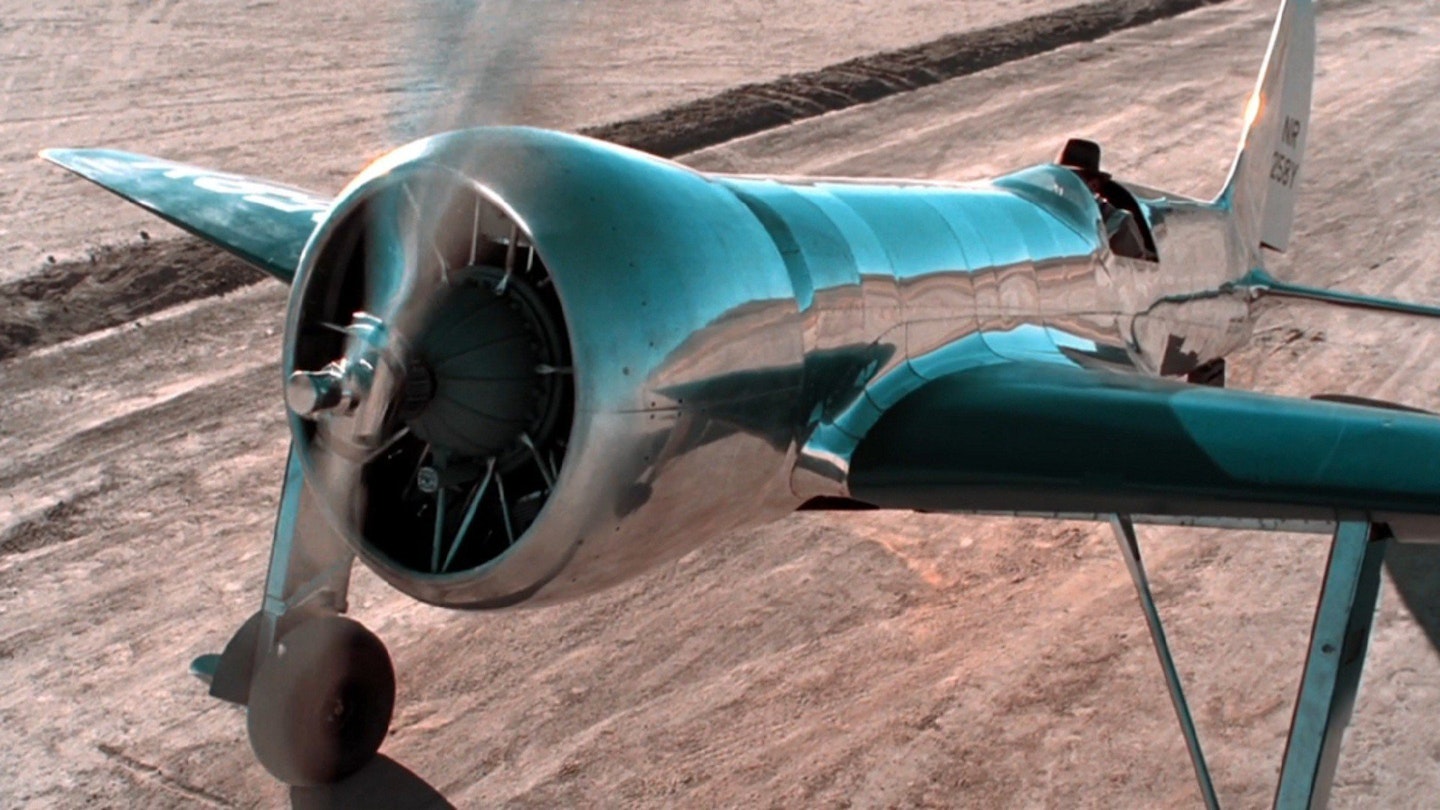

Perhaps this is why he fails to get under the skin of his subject. Nevertheless, Hughes' story is fascinating. It begins with the Hollywood arriviste lavishing his recent inheritance on his twin passions simultaneously, amassing the world's largest private air force and sinking an unprecedented $4 million of his own money into Hell's Angels, his tribute to World War I fighter pilots. Given Scorsese's infallible eye - abetted here by production designer Dante Ferreti and costumer designer Sandy Powell - the recreation of '20s Hollywood is immaculate.

There are also several magnificent set-pieces to savour, among them Hughes' heroic orchestration of the Hell's Angels dogfight sequences from the open gun turret of a bomber and, later, a spectacular plane crash in which Hughes, flight-testing one of his own designs, rips through the rooftops of Beverly Hills. In between, mustering every ounce of his stylistic verve, Scorsese chronicles Hughes' stormy romantic dalliances with Katharine Hepburn (Cate Blanchett) and Ava Gardner (Kate Beckinsale), and his draining, dragged-out fight with Pan Am chief Juan Trippe (Alec Baldwin), who was determined to put his TWA airline out of business. As the visual tone shifts to keep pace with the times - the pastel hues of the '20s giving way to the oversaturated Technicolor '40s - Hughes himself transmogrifies from a brazen young mogul into a twitchy, paranoid obsessive who, against the backdrop of failed relationships and a besieged business empire, struggles to keep a grip on his failing sanity.

It's in these later scenes that Leonardo DiCaprio shines, dispelling fears that he hasn't the weight to carry such a complex, forceful role. He's mesmerising in the moment when Hughes rears back from the brink of madness to face down a corrupt senator (a superb Alan Alda) over allegations that he cheated the US Air Force.

Yet in spite of the lush production values, absorbing narrative and outstanding performances, the question of what, exactly, made this extraordinary man tick remains unanswered. When he's pulled from the flaming wreckage of his plane, the only words he manages to croak are, "I'm Howard Hughes, the aviator". And we know precious little more of him than that.