Baltimore is one of the least celebrated of major American cities. Barry Levinson was brought up there and Avalon is the third occasion - after Diner and Tin Men - on which he has attempted to redress this imbalance by using it as a setting for his work. Indeed, were Levinson not coming off Rain Man it is doubtful that he would have been able to finance such a commercially unlikely project as this sober but quietly spectacular film with no room for stars, this tale of how one family moves from Eastern Europe to the Eastern United States and there, over a couple of generations, disintegrates.

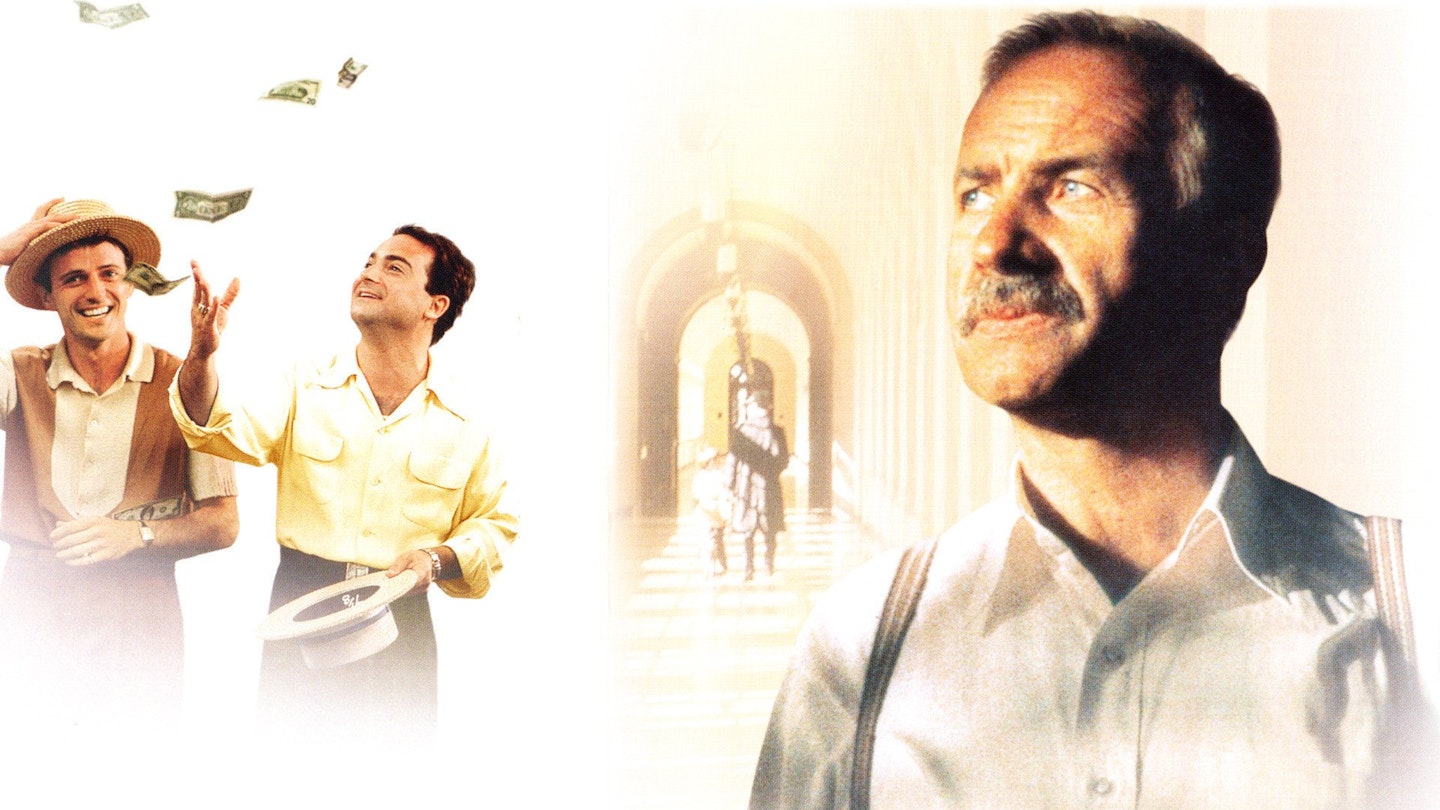

The Krichinskys are not the huddled masses of New York's Lower East Side but the industrious lower middle classes who move to the suburbs on the back of the post-war consumer boom, making their money selling discount fridges, cookers and, significantly, televisions. They have little sentiment to spare for the old country. Sam, the grandfather whose reminiscences provide the spine of the film, recalls arriving in Baltimore on July 4th 1914 as fireworks illuminated the night sky: "It was the most beautiful place I had seen in my entire life." He settles in the new Utopia of the Avalon district.

The Krichinskys start off as a cliche-extended family, ceaselessly cooking and eating, squabbling and retailing old anecdotes, three and four generations under the one roof; they finish up as a bunch of nuclear units, picking at TV dinners with Milton Berle and failing to turn up to funerals. Their disintegration is wrought not by crime, war or disaster; instead the Krichinsky family is sundered by prosperity, time and television.

The art direction is superb throughout, notably in the opening sequence as young Sam wanders the streets of Baltimore like a dazzled pilgrim entering paradise, while Randy Newman, who has been in this era before with Ragtime, contributes excellent music. Thanks to uniformly splendid performances (particularly from Mueller-Stahl as Sam) Levinson elicits poignant humour from the inconsequential specifics of family life, many culled from the reminiscences of earlier Levinsons: the uncle storming out because the Thanksgiving turkey was carved in his absence; the boy disturbing a wasp's nest; the ambitious young cousins shooting TV commercials for their own discount warehouse; and, best of all, the aged brothers wracking their brains to remember the name of a favourite John Wayne movie. That's the one about the stagecoach.