"The worst part of being old is rememberin’ when you was young,” Alvin Straight remarks sagely in David Lynch’s The Straight Story, but Austrian director Haneke’s Palme D’Or winner suggests an altogether less whimsical reality: that the hardest part of advancing years may, in fact, be watching helplessly as a loved one slowly succumbs to the ravages of old age.

Veteran French actor Jean-Louis Trintignant gives a sensitive, unsentimental performance as Georges, the former music teacher who struggles manfully to cope as his beloved wife becomes a shadow of her former self. Early in the film, Georges tells Anne a story which, she says teasingly, might tarnish her image of him, even after all their years together. It’s a telling exchange, for Georges is about to witness the slow disintegration of everything that makes her Anne, as a series of strokes and subsequent onset of dementia reduces her to little more than a helpless child, no longer able to play, or even appreciate, the music which has been her life, while her erratic behaviour tests Georges’ love, tolerance and compassion to superhuman limits.

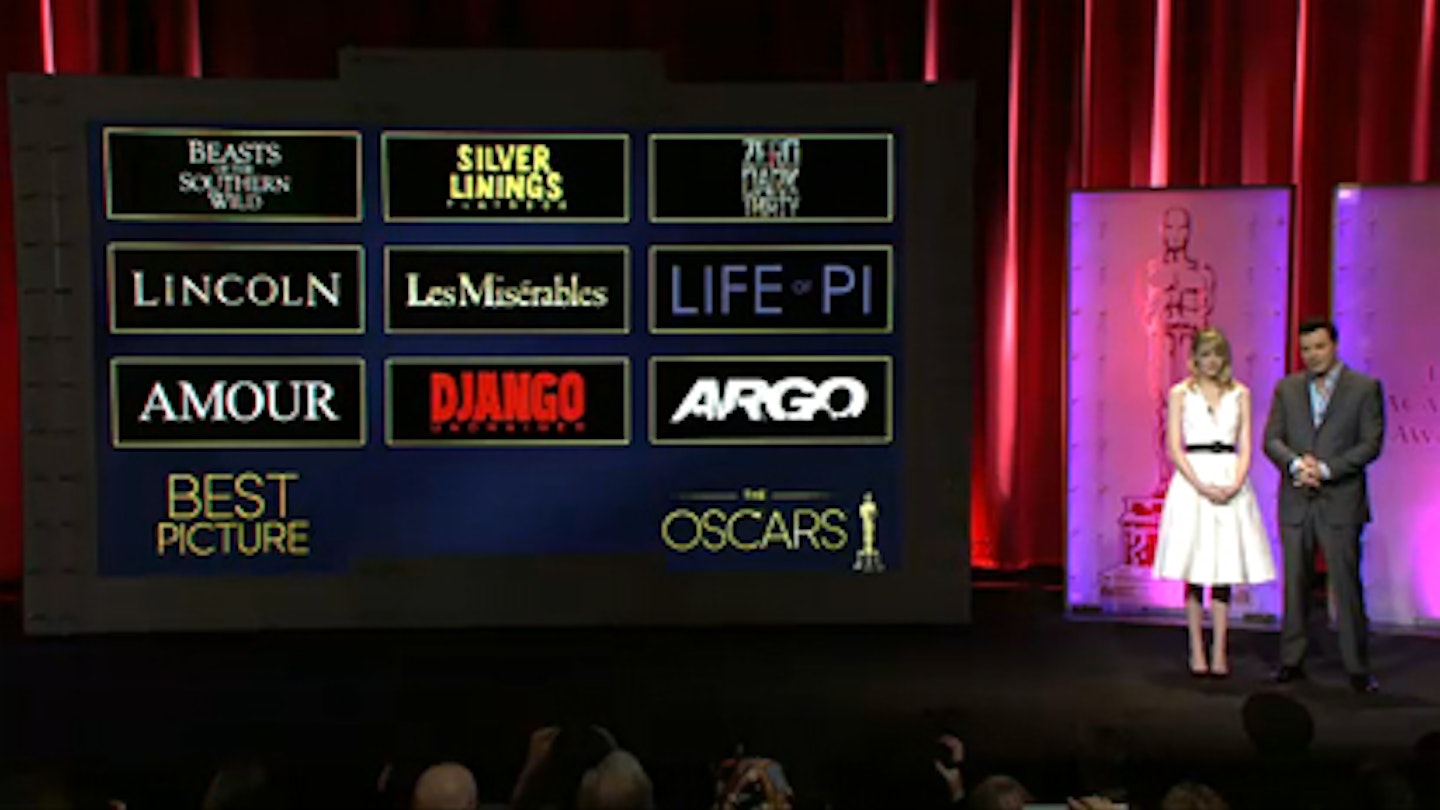

It sounds like a depressing cinema experience, ‘the feel-bad movie of the year’, and many may find it unbearably sad. But Haneke’s rigorous insistence upon emotional honesty means that no tear shed is unearned, no feeling manipulated (there is, for example, no non-diegetic music), and that the film is, crucially, devoid of sentiment. Besides, the title is no accident: in the course of two hours, Haneke suggests that the ultimate test of a lifelong passion may come not in its first flourish, but in the compassion of its very last days, and that while love cannot conquer death, it can give life’s bleakest moments a run for their money. Viewed from this angle, Amour becomes not only one of the greatest films ever made about old age, but a love story for the ages.