When Oliver Stone announces he's making another film, it's not so much a case of taking notice as taking cover. His is not the cinema of clinking teacups and subtle interplay; this is cinema as blitzkrieg: elemental, outrageous and barely tamed. And when Oliver Stone announces he's making a film of the life of Alexander The Great, the Macedonian king who trampled over half the known world, by Zeus, you'd better be prepared. Alexander looks and sounds glorious, depicting a far-off world spread with intricate detail and expansively scored by the aural grandeur of Vangelis. The battle scenes extraordinarily reconstruct the horror of war in a time when seeing the whites of your enemy's eyes was a tactical necessity. If Troy was tame and bloodless, Alexander is wild and drenched in carnal violence.

It takes three tours of duty in Vietnam to understand such visceral madness, and Stone takes his camera tight into Alexander's demented eyeballs before pulling back and letting the blood spill. In what must be the most monumental scene of any career, described in arch slow-motion from about 62 camera angles, Alexander on his faithful steed rears up before a similarly rearing armoured elephant. It's a tremendous surge of purest spectacle; the film never feels so alive as when it's immersed in death.

And yet! And yet! This is no Spartacus, or even a Braveheart. Stone's determination to bang home big themes, crackling with Freudianism, unsettles his storytelling. There's something overbearing, almost bullying, about this abbreviated tour through a decade-long campaign, pinpointing loud, emotional moments rather than dramatically satisfying ones.

The first hour is spent prying on the younger Alexander's fractious relations with his demented parents, the psychological fuel to his all-conquering mania. With hints of incest or worse, Jolie joyously chews it all up and spits it out with sexy vigour - it appears her son may have swallowed up nations just to shut his mother up.

Just as in JFK or Nixon, Stone once again ponders the blurring of history and myth. The story is weaved in flashback by Hopkins' elderly Ptolemy, who judges the frailties of the real man before carefully omitting such details from the record. These, though, are truths still hotly disputed, so the script keeps fretfully explaining itself. Alexander's bisexuality, for example, is dealt with maturely, but repeatedly.

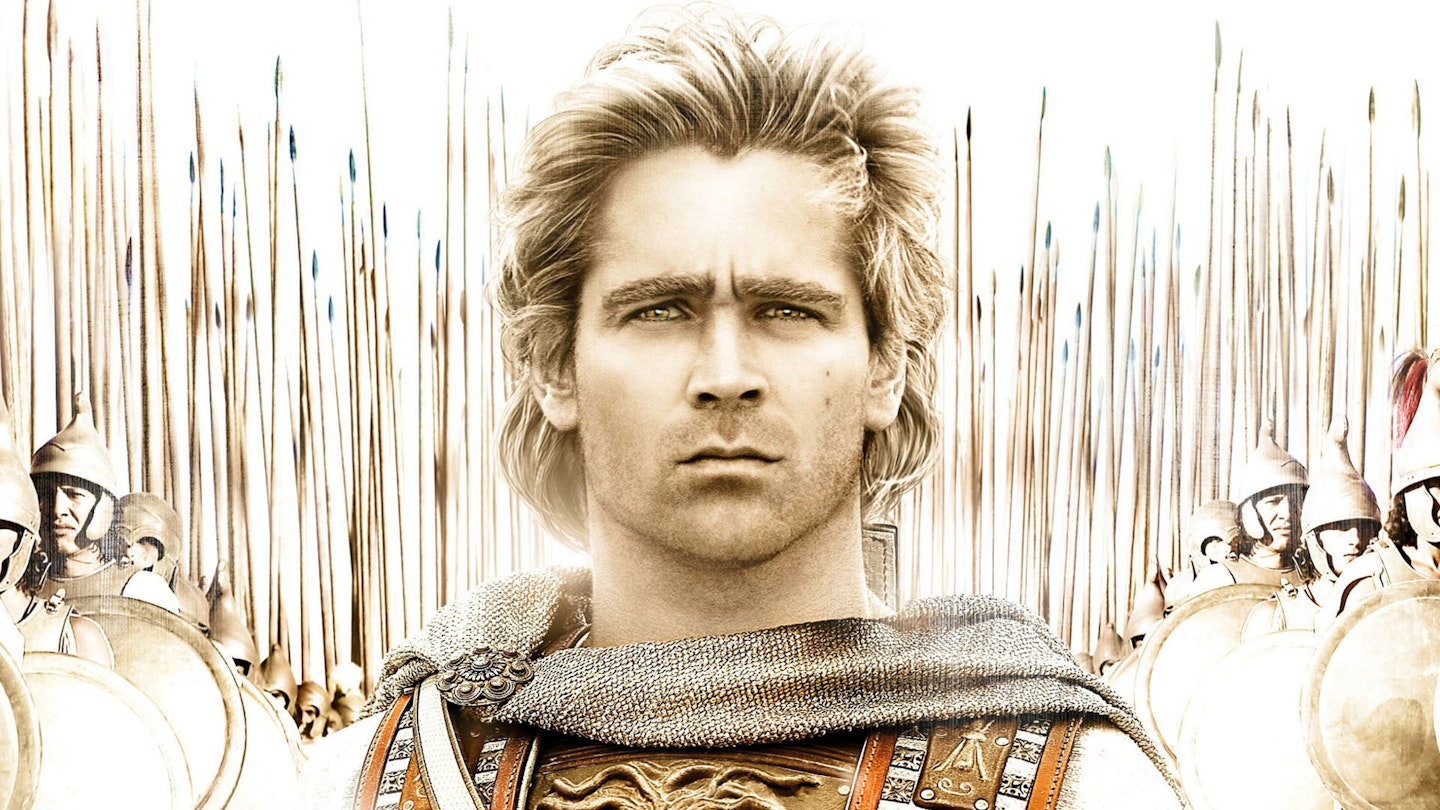

It's convienient to note the parallels between the director's over-ambition and that of his subject, but the comparison fits. Stone pushes too far just as Alexander did, aiming to give us a leader of contradictions: tyrant and diplomat, lover and killer, god and man. Poor Colin Farrell is presented with having to turn a marble icon into a fleshy sprawl of personal issues. You can feel him strain every sinew to get it right, but with his blond locks out of whack with his heavy stubble and his Dublin accent awkwardly unchanged, he is too earthy, that one-of-the-boys persona unshakeable. Where is that spark of glory that drove men 10,000 miles from home? Where is the colossus? Yes, this is a movie of spectacularly brutal battle scenes and intense attention to detail, but, as wowed as you are, you come away never truly tasting the immensity of Alexander.