It feels like we’ve been spoiled by space. Ever since Gravity seemingly changed the game, science-fiction has had to work harder than ever to impress us. It’s almost like the genre’s already peaked. Picking up the space-gauntlet, director James Gray quixotically heralded Ad Astra as being “the most realistic depiction of space ever”. And fair dos, this film is beautiful: from the glistening cinematography to artfully celestial framing to the seamless visual effects (some shots use actual photos of the moon’s surface), it all looks real.

What sets it apart from recent gravity-defying films, however, is the setting. This is a future that feels recognisably familiar and deeply plausible, a world in which space travel has become commercialised, normalised, and blighted by the same overpriced pillows as the budget airline. The wonder of space has been replaced by the mundanities and conflicts of Earth; the moon is a gaudy tourist trap and disputed territory, not unlike an episode of Futurama. Throughout, we’re drip-fed morsels of information about the new inter-planetary infrastructure and each new revelation is a delicious bit of speculative world-building, ‘sci-future-fact’ rather than sci-fi.

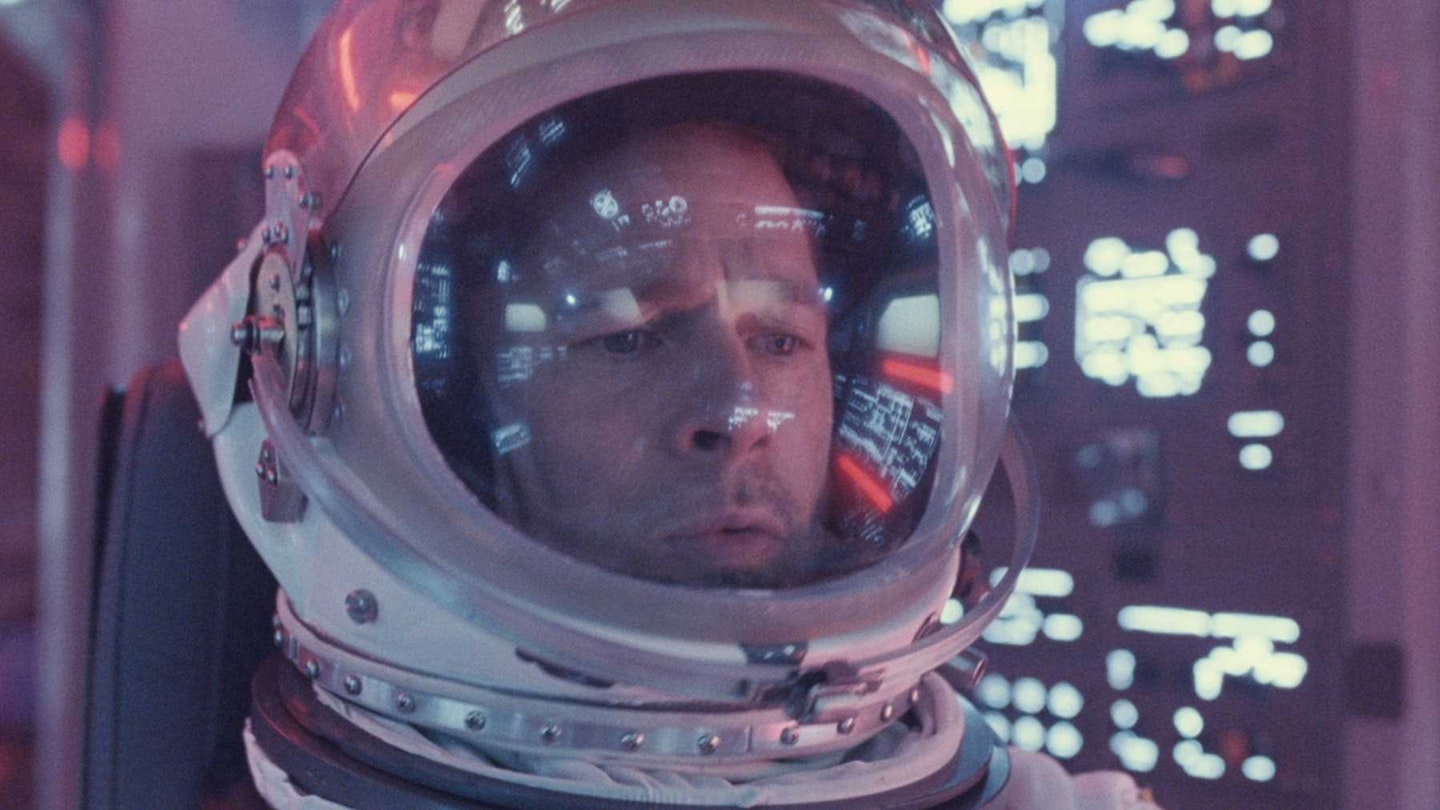

It’s a setting that also causes our nominal hero, Roy (Pitt), some serious melancholy. Outwardly, Roy is cold and uncaring, his pulse never skipping a beat, his focus always on the mission. But his pessimistic voiceover laments the deterioration of the space era and hints at some familial yearning for his estranged father, who may be behind the catastrophic electrical surges that are suddenly plaguing Earth. Truly, you don’t know abandonment issues until your dad is floating beyond Neptune.

Despite a dip in pace towards the end, it’s a fantastically well-staged adventure.

Roy’s narration sometimes sounds like a maudlin teenage diary (“I’ve let so many people down,'' he whines at one point), but he’s a fascinatingly flawed hero, as incapable of emotions as he is a capable astronaut. His odyssey through the inconceivable vastness of the solar system has something of Willard sailing up the river in Apocalypse Now: confronted by loneliness in an unforgiving environment, the indifference of death stalking at every corner.

For such an ambitious film, it’s remarkably meditative; set across billions of miles, it is always only interested in Roy’s interior life, the camera trained in heavy close-up on his tired-looking face. (Spare a thought for poor Liv Tyler, playing Roy’s wife, who is often not even in focus, making her similar role in Armageddon look positively generous.)

But despite a dip in pace towards the end, it’s also a fantastically well-staged adventure. There’s a (literally) head-spinning opening sequence at the ‘International Space Antenna’, an encounter with an unexpected space-primate, and a moon-buggy chase which offers a thrilling preview of what ‘Fast & Furious In Space’ might look like. It has fun, even if its leading man doesn’t.

Through all this, it manages to ponder the existential questions facing humanity, and brings it back to the humanity we need to face. That, above the realistic depictions of space, is probably its real achievement.