It’s an unwritten law in Hollywood that, once a star gets to a certain level of paycheque, it’s nigh-on impossible for them to play a balls-out, ruthless bad guy. Sure, their character can commit evil, but only if they’re also made layered, sensitive and preferably conflicted.

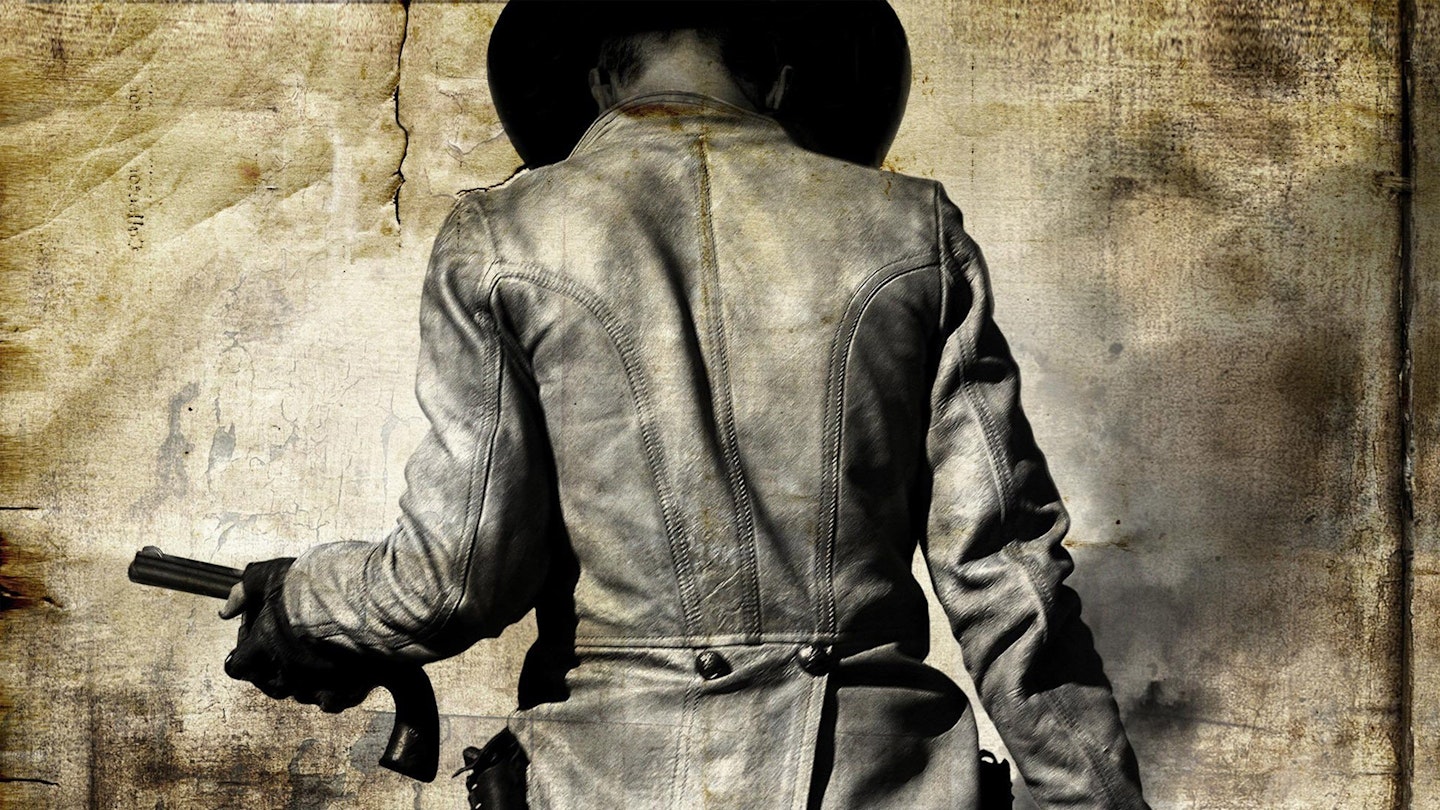

See, for example, Collateral, in which Tom Cruise’s hitman was somewhat redeemed by a love of jazz and the existential urge to find his place in the universe. Likewise, in this James Mangold Western, Russell Crowe’s black-hatted, black-hearted outlaw Ben Wade is the sort of rotter who can murder a defenceless man in his sleep, but also an artist, sketching during spare moments. He loves and understands women. And even when he’s evildoing, he has a twinkle in his eye that tells you that - hey! - he’s not all bad.

The mention of Collateral wasn’t accidental: that movie was written by Stuart Beattie, who wrote 3:10 To Yuma’s final draft. Indeed, 3:10 comes on like a Wild West version of Collateral, with the villain, so seemingly secure in his own skin, pushing a wimpy underachiever - Christian Bale’s desperate, disabled rancher, Dan Evans - into finally making a stand, while revealing severe deficiencies in his own approach to life.

A remake of the 1957 Delmer Daves Western, it retains the High Noon-in-reverse B-movie trappings, but ups the two-hander to A-list status and adds a new middle section that tracks the progress of the small posse shepherding Wade to the titular prison train.

It’s an extended sequence that takes in an Apache attack and several brutal murders, and allows Mangold to shade the supporting roles (Ben Foster’s psychotic gunslinger and Peter Fonda’s gnarled McElroy are standouts). Yet the movie always comes back to the interplay between Bale and Crowe, in scenes laced with a mutual respect that, you sense, stems more from the actors themselves than the characters.

At first, Evans is bland compared to the broad, colourful palette of Wade. But Bale, greasy and put-upon, manages to make the hobbling Evans, tortured by his failure to support his family, likeable, noble and sympathetic as he finds that there’s more to marshalling Wade than mere money.

Still, this is Crowe’s movie. He invests Wade with a callous streak - “Even bad men love their mothers,” he quips, before pushing someone off a cliff - but also flashes of humanity, as he begins to like Evans almost despite himself. As we said, Wade’s clearly not all bad, but the real skill in Crowe’s performance is that he keeps us guessing, as Wade tries manfully to resist the redemption he can feel tugging at him.

Then, Mangold has always been an actors’ director (just ask Reese Witherspoon). Sadly, though, he doesn’t quite deliver on the action front, particularly in the final shoot-out. Despite the inbuilt ticking clock, there’s precious little tension as the two men race towards their destiny through a shower of squibs and splinters - and then, out of nowhere, comes a character development so baffling that it feels like Mangold left out a scene, Grindhouse-style.

It’s a real shame to see this otherwise solid train derail so late in the day.