Generally, a film like The Promise wouldn’t have generated so much pre-release notoriety. But after just three screenings at the Toronto International Film Festival last year, it somehow amassed more than 50,000 one-star ratings on IMDb. Unless Canadian cinemas are considerably bigger than those in the UK, that’s an unlikely tally. And the smart money is on it being due to its subject matter — recognised as historial fact in the rest of the world, the Armenian genocide is a controversial topic in modern Turkey, even a century on from the atrocities. But, as seems to be the case with so many films that provoke such a reaction, it’s blander than the hubbub suggested.

It’s difficult to escape the feeling we should be glad The Promise exists.

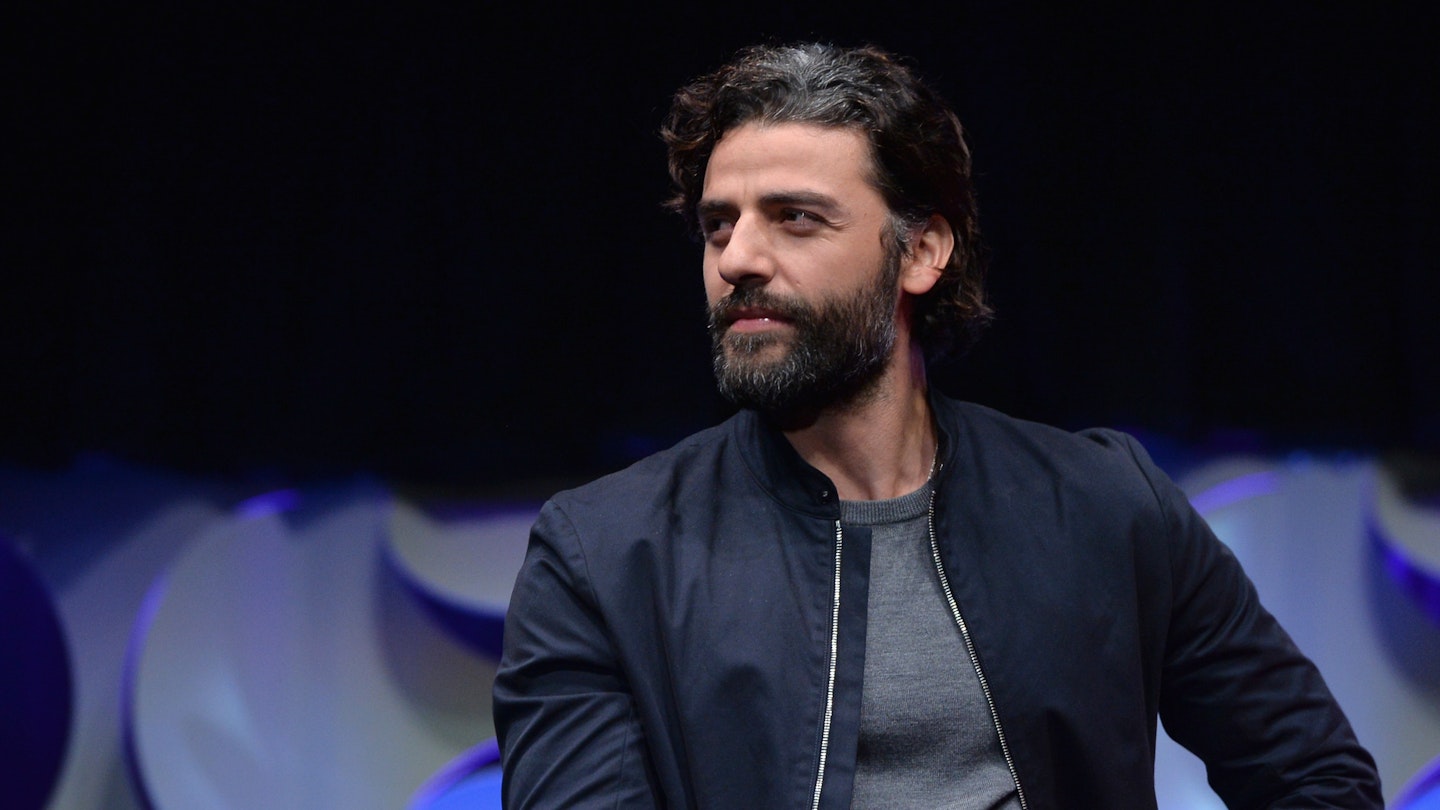

On paper, The Promise has a lot going for it. Isaac and Bale are reliable, big things are expected of Le Bon, and director Terry George has form with solid issues dramas like Some Mother’s Son and Hotel Rwanda. The whole production wasn’t short of cash, too, with the late billionaire Kirk Kerkorian (an Armenian-American, and former owner of MGM) providing a hefty budget. He died just before production, but his cash is all on screen: whoever runs the extras agencies near the Spanish locations presumably had a lovely Christmas as a result.

That said, more work on the script wouldn’t have gone amiss. The central love triangle is clearly meant to sugar the pill of the wider narrative of mass murder, but in

trying to pay attention to both, the final product falls between two poles. The central trio get into their fractious holding pattern pretty early, and the rest of the film is them being separated and reunited in various combinations as the grim events of the genocide unfold around them. We stay on a very narrow range of characters, with little interest paid to the wider context around them; Schindler’s List’s wide-angle, almost sociological approach to such horrors remains the gold standard. Armenians had been subject to discrimination in Turkey for decades — focusing on a few relatively bourgeois victims almost downplays the horrors, which can’t have been the goal.

There’s also an almost total lack of irony, which can lead to a po-faced stuffiness but here works surprisingly well. And Isaac is chiefly responsible for this, turning in a sincere performance that sells the situation Mikael finds himself in. His flair for suffering (an under-discussed string in any actor’s bow) sustains things through scenes which threaten to turn to cheese at any moment, and Isaac is far more complex and compromised than the stiff opening moments would initially suggest. He’s a character, rather than a cypher, and it saves the film.

In the end, though, while The Promise lacks depth in both its strands, it tackles such an underexposed moment in human history, it’s difficult to escape the feeling we should be glad it exists.