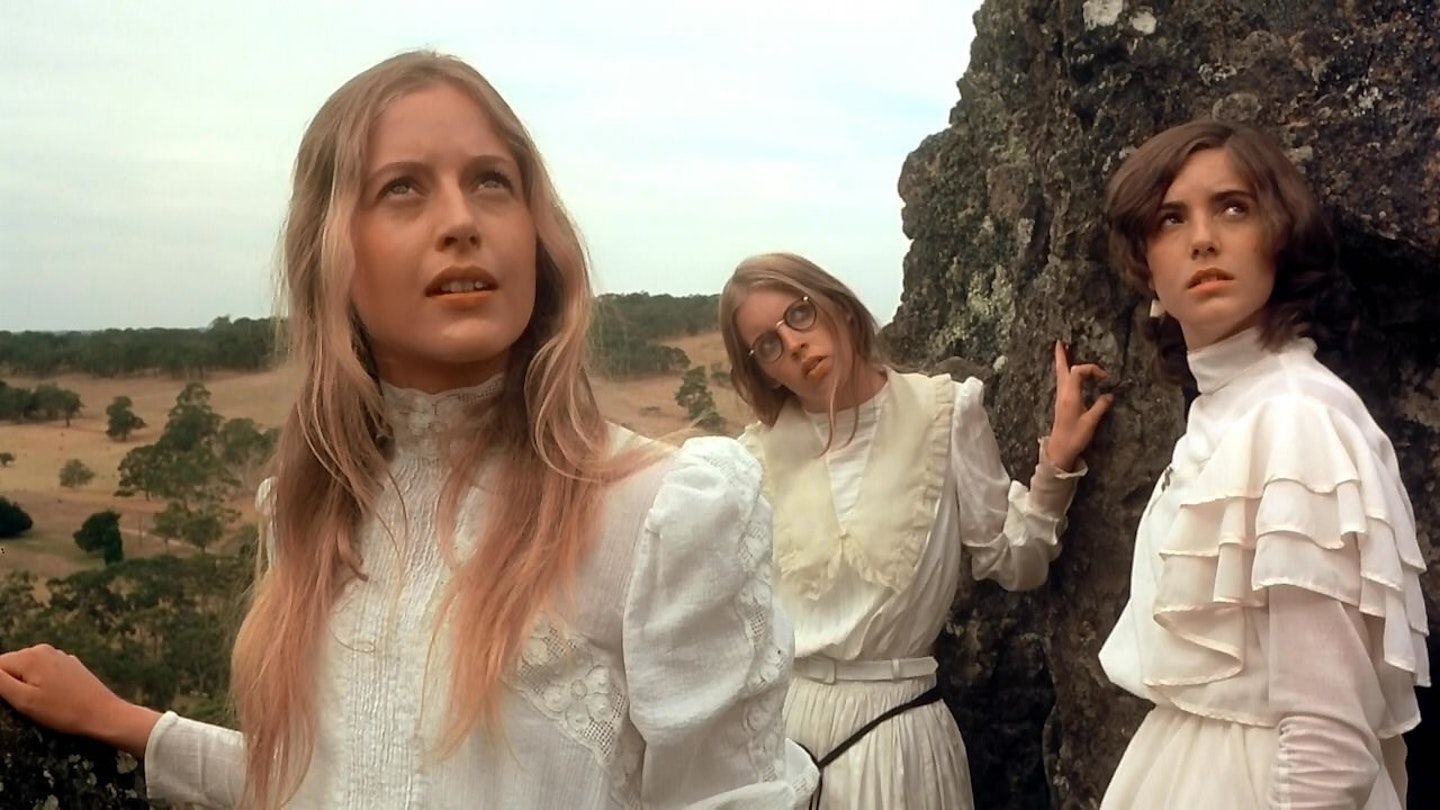

A haunting and compelling oddity from Australian master Peter Weir, that doesn’t fit easy categorisation; it is part mystery, part horror, an impressionist poem to lost innocence. Although since considered based on a true story, it is, in fact, merely an adaptation of Joan Lindsay’s novel, but Russell Boyd’s cinematography is so sumptuous and captivating it is little wonder watchers felt like they were stepping into some peculiar reality; his visionary camerawork keeps resting on plants, animals, hives of restless insects, the screen almost bursting with wildness. Weir’s emphasis is on nature’s alien quality, how these prim girls are set against unknowable forces.

That he also refuses to answer the questions the film presses upon us is a tactical risk, but it works because he is not setting it up as a straightforward narrative. He is playing with themes and images, and only elusively with a plot. The girls that remain behind become hysterical, unable to explain what became of their friends, and there is a strong allusion to the force of nature that also exists within their pubescent bodies, as if sexual awakening can have devastating outward results — an idea exemplified when the girls are spotted barefoot in the bush from afar by a stable boy and a young English aristocrat. From their point of view, they are both angels and sirens, and when the boys follow they find no trace of them. Meanwhile, their headmistress, played with stoic force by Rachel Roberts, is determined there is a rational explanation, but no answer will be forthcoming. It is a dreamlike journey with no resolution, just fragments and suggestions, leaving an almost painful sense of longing for these lost creatures.