There had, of course, been college comedies since Harold Lloyd made The Freshman in 1925. However, Ramis and Kenney quickly realised that nobody had yet attempted to capture the student days during the halcyon hiccup between the end of the '50s and the death of JFK in 1963.

The counterculture revolution that would sweep through America later in the decade had its roots in the liberal campuses of the early '60s. More importantly, at least in terms of dramatic conflict, those same colleges had also organised social life into units that attempted to preserve in amber contradictory and entirely ancient traditions - the fraternity system.

While the Animal House treatment was struggling towards a shooting script, Saturday Night Live was busy becoming a phenomenon. Reitman's original idea had been to steal back as many of the SNL players as possible. Indeed, although the writers avoid much character shading - the inhabitants of Delta House are designed as archetypes that any college alumnus would recognise - the parts were nevertheless tailored to the distinctive talents of that famous first troupe.

Chevy Chase was perfect for the smooth operator, Otter; Bill Murray a good fit for the deadpan, lovelorn Boon; Dan Aykroyd would enjoy himself as the huge, hog-riding D-Day; and for Bluto, the Animal House's prize animal, there was only ever one choice: John Belushi. Sadly, the SNL colleagues proved too competitive to share equal billing and eventually only Belushi said yes. In the end, of course, Belushi was more than enough.

It is a routine mistake to describe Animal House as a John Belushi vehicle. Although the rest of the cast was eventually filled with unknowns (among the finds were Karen Allen, Kevin Bacon, Peter Riegert and the aforementioned Hulce), the script was not refashioned to promote its one TV star. Belushi would improvise if encouraged, but the outsized Bluto was more or less complete on the page.

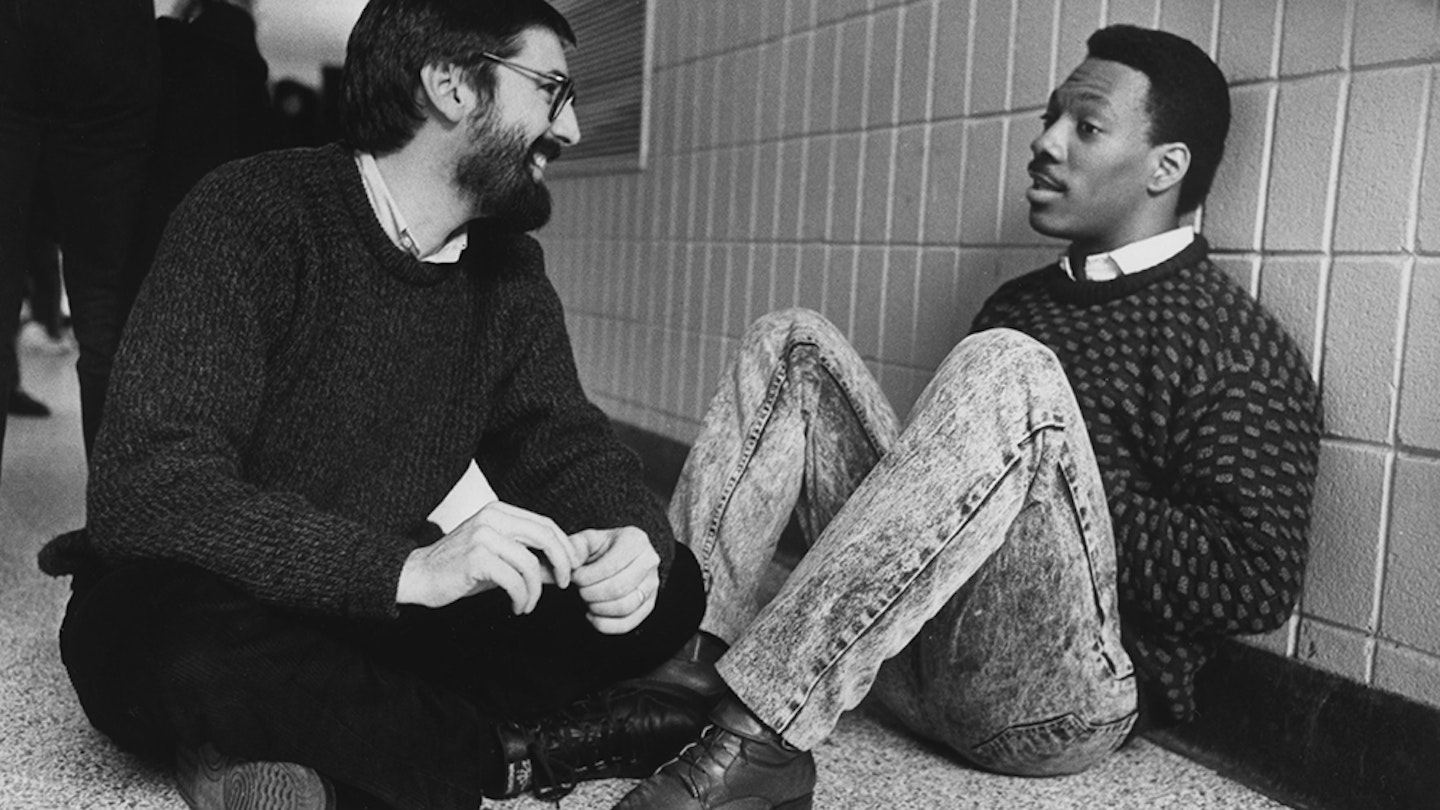

Belushi was well aware that Animal House could be his big break and, unlike subsequent engagements, he was content to be both disciplined and generous - this was an ensemble comedy. Of course, as soon as Animal House hit theatres, the reality was obvious: Belushi, with his cartoon features and signature catchphases, owned this movie. Bluto's animal appetites, alongside a goodly helping of risky sexy stuff, powered Animal House to an unprecedented $142 million at the box office, making it the biggest comedy of all time.

The impact was immediate and, together with SNL, Animal House ushered in a comedy revolution that we can still feel today. Indeed, from Elmer Bernstein's sweeping dramatic strings - perhaps the first counterpoint score in comedy - to the gleeful mixture of low-brow and lower-brow gags, Animal House is arguably the most influential comedy of our time. The action may be set in 1962, but the snobs versus slobs are battling for the soul of contemporary America, a war that National Lampoon had been fighting in print for years.

Nixon and his cronies, need we be reminded, would have lined up for the Masonic, sadomasochistic practices of Omega House. Although Animal House struck a chord with younger audiences, it was aimed at the class of í62, reminding them of who they were back then and of the world they were supposed to create.

As for National Lampoon itself, the brand still appears above the title occasionally, but it has long since ceased to be a guarantor of quality. The patchy Vacation series provided Lampoon with its solitary franchise, but it is Animal House - the original and best gross-out comedy - that remains Lampoon's sickest hour.