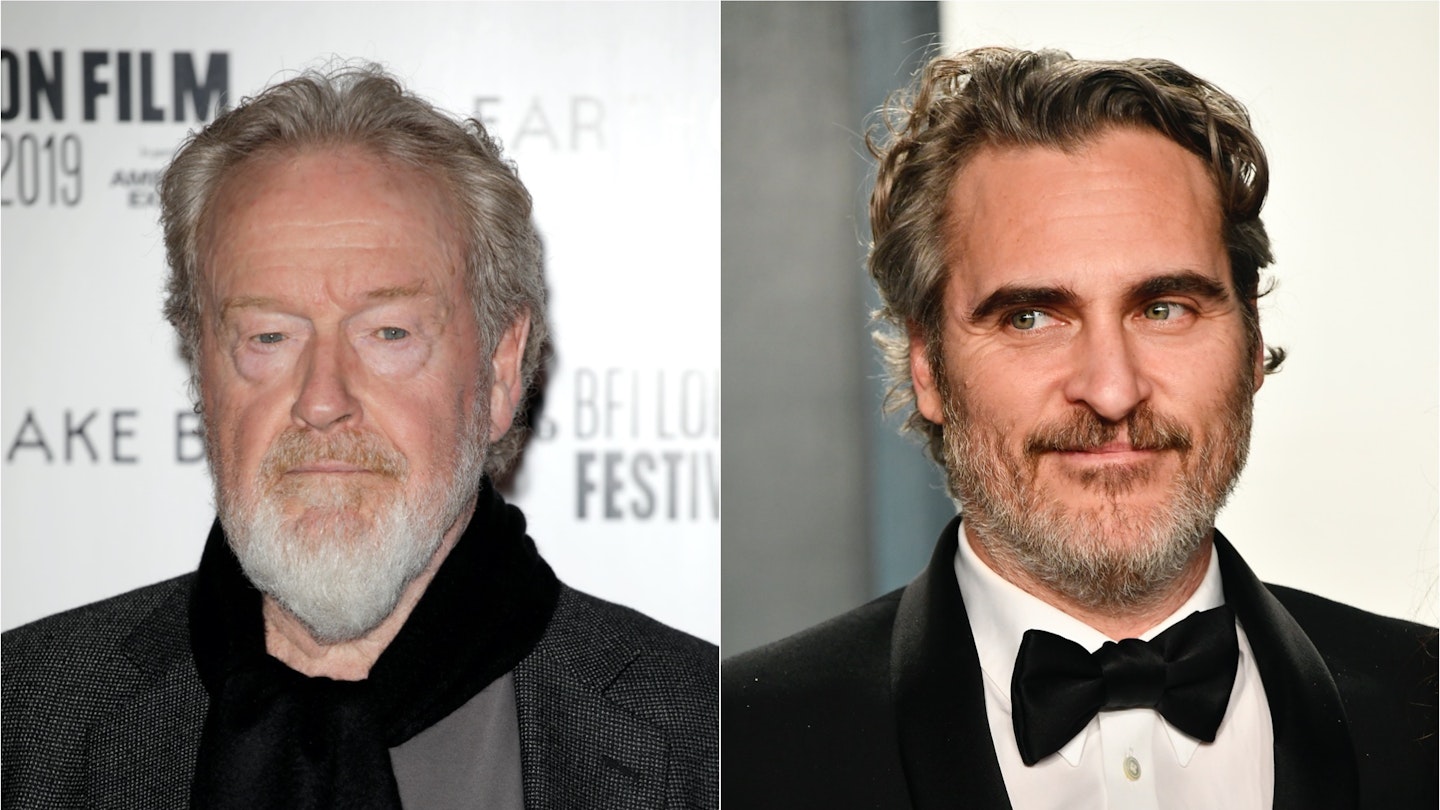

A looming deadline. Screaming newspaper headlines. The question of whether or not to pay out a vast sum of money. It’s a story for the history books — how Ridley Scott barely blinked before ordering the recasting of Kevin Spacey, one of his leads in kidnapping drama All The Money In The World, when the stories came out about Spacey’s alleged deeds of sexual misconduct. Out was Spacey, who had been caked in liverspotted latex to play octagenarian oil billionaire J. Paul Getty. In was replacement Christopher Plummer, with numerous scenes being reshot at frantic speed — and at the reported expense of £7.5 million — to make the film’s imminent release date.

May even end up getting all the awards in the world.

The story, happily for all except Spacey, ends in triumph. Plummer proves to be the best thing about All The Money In The World, grabbing the role of “not just the richest man in the world, but the richest man in the history of the world” by the throat. His performance ensures that what could have been a live-action Mr. Burns — Getty actually has hounds on one of his estates, presumably for the purposes of releasing — becomes the fascinatingly complex, icy heart of the film. Plummer has surely already been offered a reboot of K-Pax.

It’s not hard to see why this based-on-true-life story was not only seized by Scott, but is the subject of a forthcoming Danny Boyle TV series, Trust. Think a pulpy mash-up of Dallas and Ransom: in the early ’70s, the 16 year-old grandson of an uptight oil tycoon is kidnapped by Italian thugs and imprisoned in a grimy cell. His mother is desperate to get him back; his father is too drug-addled to care; his pennypinching pop-pop refuses to part with a single cent, unwilling to lose face or inspire further kidnappings. It’s juicy, juicy stuff, replete with grim face-offs in shadowy rooms, desperate phone calls and dark threats. Scott, who pulled off a somewhat larger-scale ticking-clock scenario in The Martian, goes for the slow burn. The pulse-pounding snatch happens in the opening minutes, but the tale then freezes, whizzing back in time to delve into the backstory and psychology of the man whose decision will seal the boy’s fate.

Perhaps Scott, an octagenarian workaholic himself, found himself relating just a little to Getty, a man who is never more joyful than when checking his stock-market numbers via ticker-tape. There’s a dash of sly wit to the character, mixed up with several measures of well-earned arrogance. “The mountain may not have come to Mohammed,” he says at one point, surveying his plans for a lavish new house in California, “but it sure as hell came to me.” There are perhaps a few too many stiff pronouncements of his objects-are-better-than-people philosophy, which sound like they may have been copied and pasted straight from the film’s source material, exhaustingly titled 1995 book Painfully Rich: The Outrageous Fortune And Misfortunes Of The Heirs Of J. Paul Getty. But Plummer is never hammy, despite the mausoleum greys of his various abodes, which make him look like Dracula in a three-piece suit.

Less effective is Mark Wahlberg, playing a man with an obscure job that has something to do with special-ops and involves him saying the word “deals” a lot. Basically the tough guy who Getty brings in to resolve the kidnapping, it’s a fairly one-note role, not enhanced by the fact Wahlberg keeps donning a pair of Serious Acting Glasses whenever a scene gets sufficiently intense. Michelle Williams is far more convincing as Gail, John Paul II’s ex-wife, acting up a storm as the browbeaten family outsider trying to make the numbers work before her dissolute son is turned into fractions himself.

Returning to Rome for the first time since Gladiator, Scott shoots the captivity scenes with a gleeful viscerality. Cicadas screech, the camera lurches, an ear-based torture scene is so graphically portrayed that it makes Reservoir Dogs look like Snow Dogs. Charlie Plummer (no relation to Christopher) is strong as the beleaguered, wide-eyed John Paul Getty III, though the film does miss a chance to flesh out his guardians in an interesting way, with only a ruffian-with-a-soft-side played by French actor Romain Duris given anything in the way of dimension.

As a thriller it’s consistently gripping, if sometimes a smidge reliant on cliché. As a study of how cold, hard cash can make a man’s heart cold and hard itself, it’s terrific. Scott and Plummer, meanwhile, deserve plaudits for their 11th-hour gambit. Who knows, the latter may even end up getting all the awards in the world.