You’re going to need to batten down the hatches when The Mercy is released, lest you founder in the hurricane of hot takes it will inspire. But you don’t need a galactic brain to tease out a political reading from this true story of a well-spoken Briton setting sail into a situation he is neither prepared nor qualified for and whose bloody-mindedness, refusal to countenance humiliation and total captivity to his financial backers lead to first deceit, then madness, and ultimately destruction. Director James Marsh does everything to offer commentary on current events short of casting Boris Johnson in the lead.

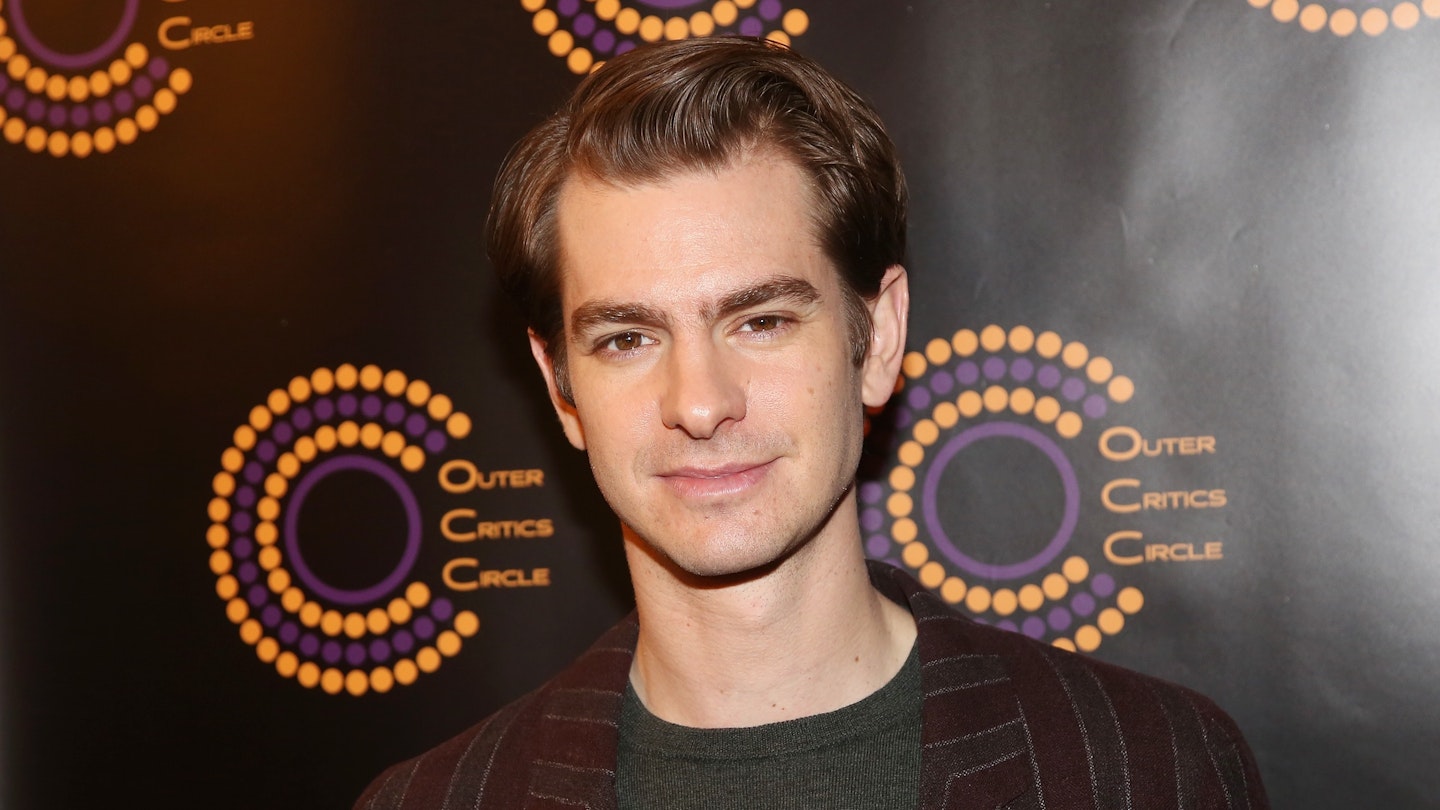

Still, The Mercy brings a lot more to the table than a busy few days on the Comment Is Free desk, not least of them Colin Firth. He’s always been a paragon of clenched-jawed English-not-Britishness, but in recent years this quality has been thrown away, ironised by Bridget Jones and the Kingsman films or fetishised to the point of cliché in The King’s Speech.

Here, he’s back in business as an avatar of well-born but non-aristo England who embarks on a round-the-world yachting expedition he is woefully under-prepared for. Half the cruelty of this uncompromising film is in seeing the nightmarish story play out across a face that brings such obvious heritage with it.

It’s a simple story of a man wandering into a situation that will kill him.

Firth’s agonies over his lies to his wife over his radio wrench their way across his face, and as his mental state deteriorates, it’s like watching a loved one lose their mind. There are lots of ways of looking at Crowhurst’s story, from a Herzog-style surrender to nature’s infinite indifference to a 1986 Soviet film’s view of him as the ultimate victim of capitalism, but Marsh and Firth wisely don’t over-egg the allegory. Make no mistake, while the opening half hour can feel like a Devon-set Heartbeat, The Mercy’s title is savagely ironic once we get to the sea.

Crowhurst’s fake reported positions, delivered as he meanders around the Atlantic in a failing boat, aren’t cheating, or self-aggrandisement. He wants to survive the ocean environment in a boat he knows won’t make it, but he can’t turn back as he’ll lose the house he put up as collateral with his sponsor. He can’t get too successful or his locations will come into question and his ‘sin of concealment’ will be exposed. Crowhurst checkmates himself into sailing the ocean in a circle while lying to his family — something that would make anyone lose their minds. That Crowhurst does all this while trying to muddle through, as is putatively the British way, is the cruellest twist of all.

Whatever reading you want to assign to this, and there will be many, it’s a simple story of a man wandering into a situation that will kill him, and doing so mostly because he wants to be good egg. In truth, its commitment to being a story of suicide-by-pluck make this not exactly one to put a spring in your step, but what a self-portrait for Britain to produce.