The central image of Mary And The Witch’s Flower has a ring of familiarity: a young pre-teen girl clutching a magical broomstick, accompanied by a sarcastic cat. The film’s surface similarities to Hayao Miyazaki’s 1989 coming-of-age story Kiki’s Delivery Service are no accident, but this goes beyond homage. Mary is the first feature from Studio Ponoc, created from the ashes of Studio Ghibli with a team boasting former Ghibli staff including lead producer Yoshiaki Nishimura. The animation and storytelling approach is near-identical to the iconic Japanese animation house, but the new studio’s creation marks a respectful cap on the legacy of Ghibli founders Miyazaki and Isao Takahata, who bowed out with The Wind Rises and The Tale Of The Princess Kaguya respectively in 2013.

On directing duties is Hiromasa Yonebayashi, director of Ghibli films Arrietty and When Marnie Was There. While those films were stately and sedate by Ghibli standards, Mary has a much more adventurous tone — it even kicks off with an eye-popping fully blown action sequence, in which a young witch makes a daring broom-assisted escape from a blazing fortress, pursued through the sky by malicious flying creatures. It’s thrilling stuff, nodding to Miyazaki’s penchant for propulsive airborne action, but with a slicker, more modern sensibility.

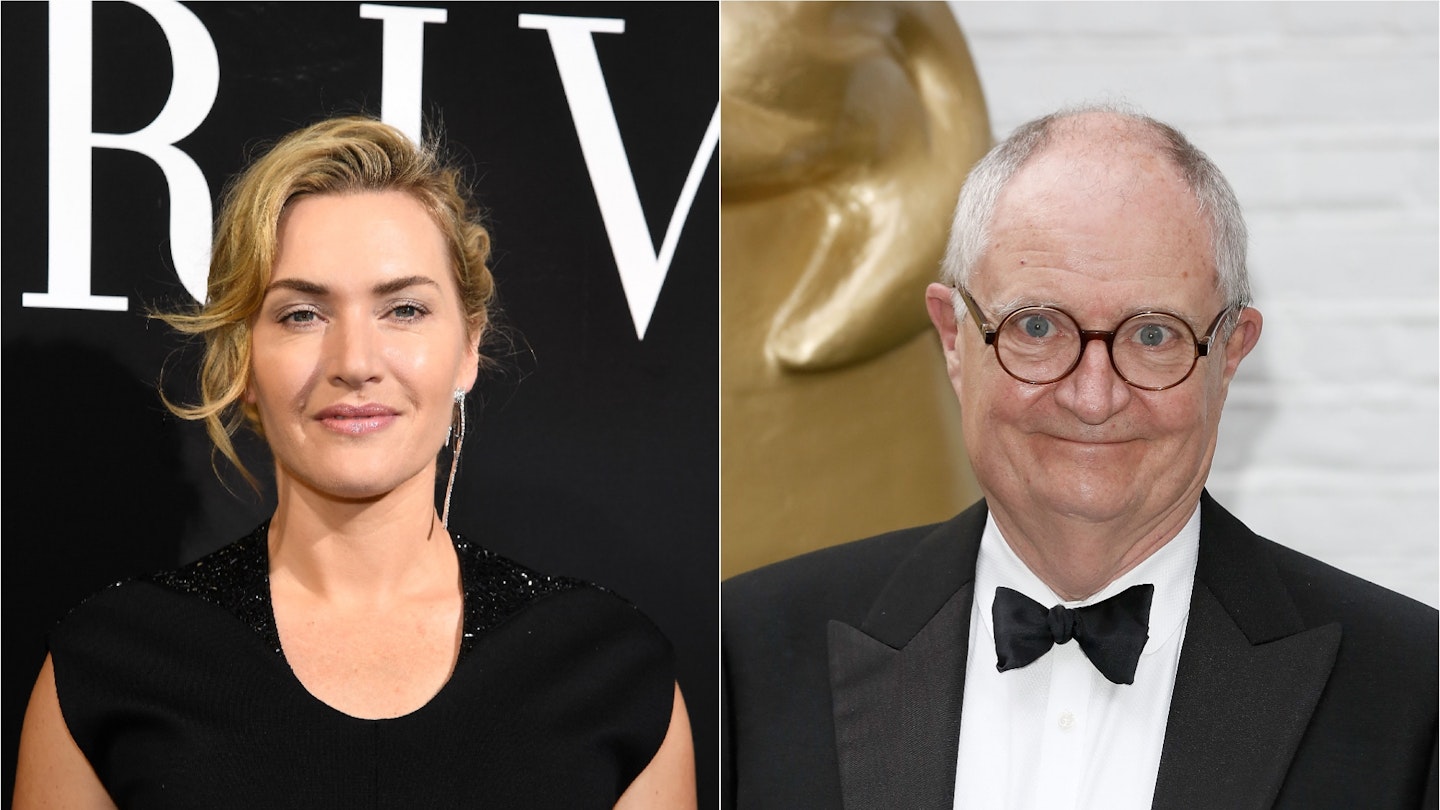

From there we meet Mary, a typically Ghibli-esque heroine — a bright, restless and inquisitive girl, eager for summer to end and school to begin. Both in the original Japanese language and British-dubbed versions (in the latter she’s voiced by The BFG’s Ruby Barnhill), she makes for a charming and boisterous lead. Her boredom subsides when she discovers a ‘fly-by-night flower’ and a hidden broomstick in the forest, kicking off an engrossing plot at magical school Endor College and beyond. If the early Endor sequence feels like an anime Harry Potter, it soon morphs into a Miyazaki-inflected morality tale that finds beauty in the power of nature, and warns of exploiting it for personal gain.

The animation here displays dazzling touches that are vibrant even by Ghibli’s standards, bolstered by Takatsugu Muramatsu’s especially beautiful score. Like Yonebayashi’s previous efforts, it lacks some of the wilder and weirder instincts of vintage Miyazaki, while a lovely story thread connecting Mary and her great aunt deserves more screentime. But these are minor quibbles — Ponoc’s first film is Ghibli magic through and through, destined to please existing fans and win over new ones.