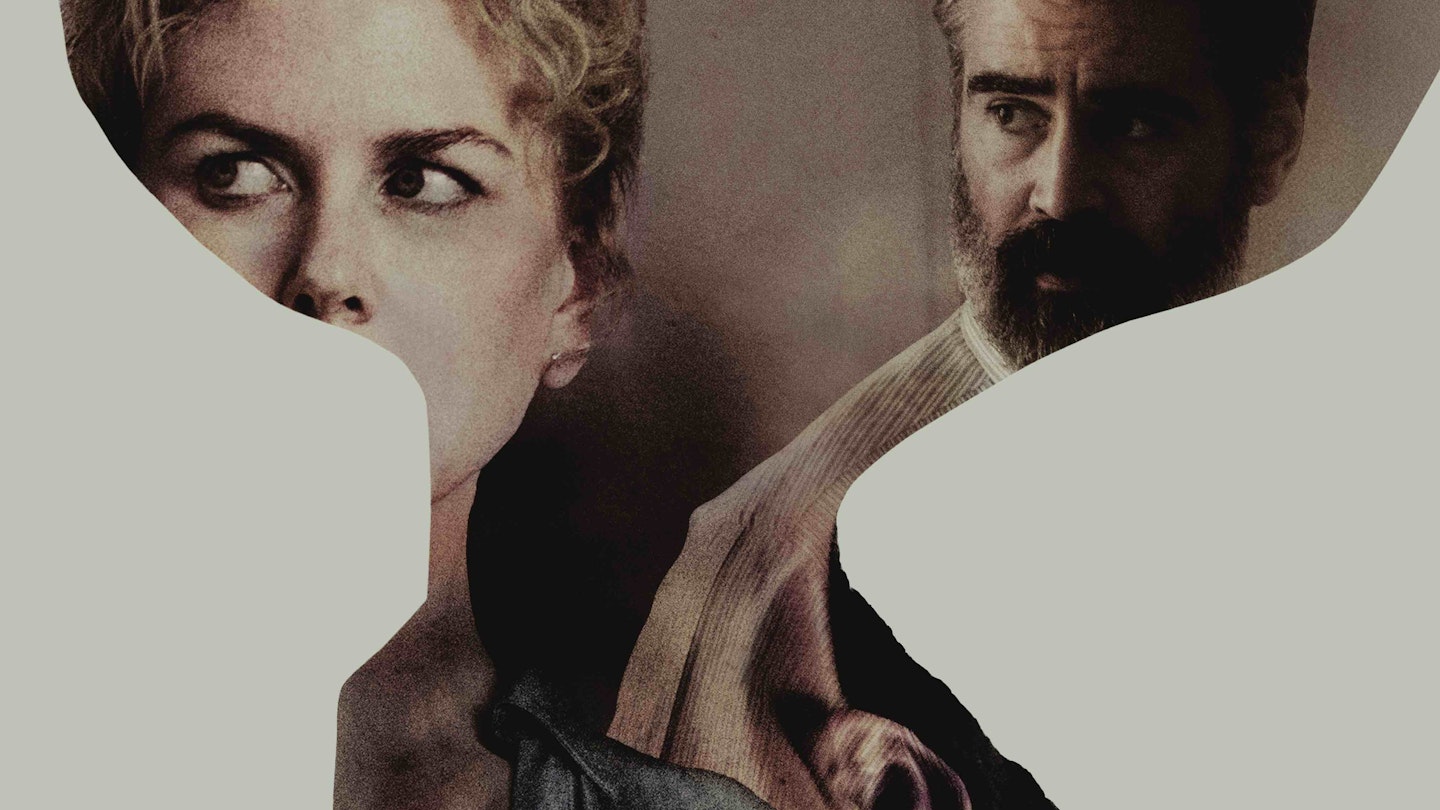

The Grand Unified Theory of Colin Farrell goes like this: above a certain budget point (Minority Report being the notable exception), he’s awful. Get him in something where the accommodation isn’t quite as comfy, with a director who’ll stretch him, and he’s quietly become one of our finest actors.

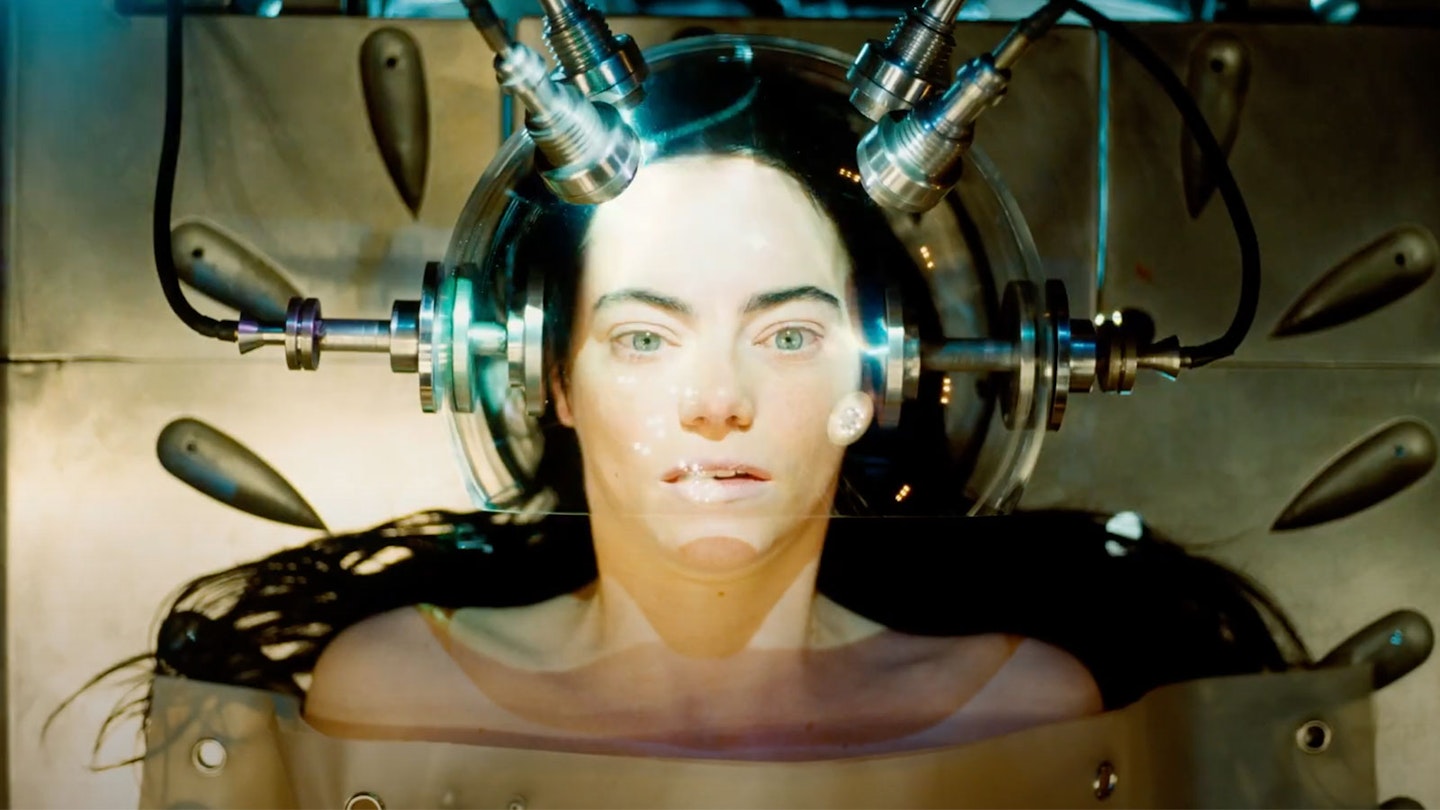

An unforgettably unnerving experience.

This, his second collaboration with Dogtooth director Yorgos Lanthimos after 2015’s well-received The Lobster, is another piece of proof for the theory. Who, watching S.W.A.T. back in 2003, would have imagined that in far-off 2017 Farrell would be delivering a subdued performance as

a weak, tested man that bears comparison to Dustin Hoffman’s work in Straw Dogs?

Farrell is Steven Murphy, a surgeon with two beautiful children and a loving wife played by Nicole Kidman. As if that weren’t cosmic reward enough, Kidman happily submits to his particular kink — somnophilia. Basically, she lets him have sex with her while she pretends to be asleep.

But this predilection is far from our first hint that all may not be well in the Murphy household. And the darkness under the carpet is finally dragged into the light with the arrival of Barry Keoghan’s Martin. Keoghan has an inherently sinister presence, and he is terrifying here.

After Martin insinuates his way into Steven’s life by showing up at his hospital, Steven invites him into the family home for dinner. This is a film from the man who made Dogtooth, so we’re not in routine life-invasion territory: everything is intentionally a smidgen off, from the camera work to the flat performances to the oddly personal turn almost every interaction with Martin takes.

The cards are soon on the table: Steven was responsible for Martin’s father’s death, and now every member of his family will first be paralysed, then haemorrhage, then die — unless Steven chooses one to kill himself.

Farrell provides much of the weight as he gradually realises the completeness of his no-win situation. For an actor it’s become routine to say was surprisingly good in something, he’s genuinely sensational here.

Lanthimos, too, turns in terrific work with regular DP Thimios Bakatakis. If the plot sounds a tad familiar, perhaps some unholy stepchild

of Lynch and Haneke, its delivery is all but unique. The visual style somehow contrives to be unflashy and highly Expressionist at the same time, providing an eerie stage for the deliberately monotonous performances and lending even mundane moments with a lifetime-in-therapy’s-worth of unease and disquiet.

There’s a lot to get your teeth into here, from flawed and lying masculinity being called out to the nature of guilt and responsibility to the morality of instrumentalising human life — but, more than anything, The Killing Of A Sacred Deer is an unforgettably unnerving experience.