Steven Soderberghs Kafka is the most famous modern example of the dreaded Second Film Syndrome. The follow-up to the director's internationally acclaimed Sex, Lies and Videotape, it was judged a pretentious failure and only received a UK release three years after production.

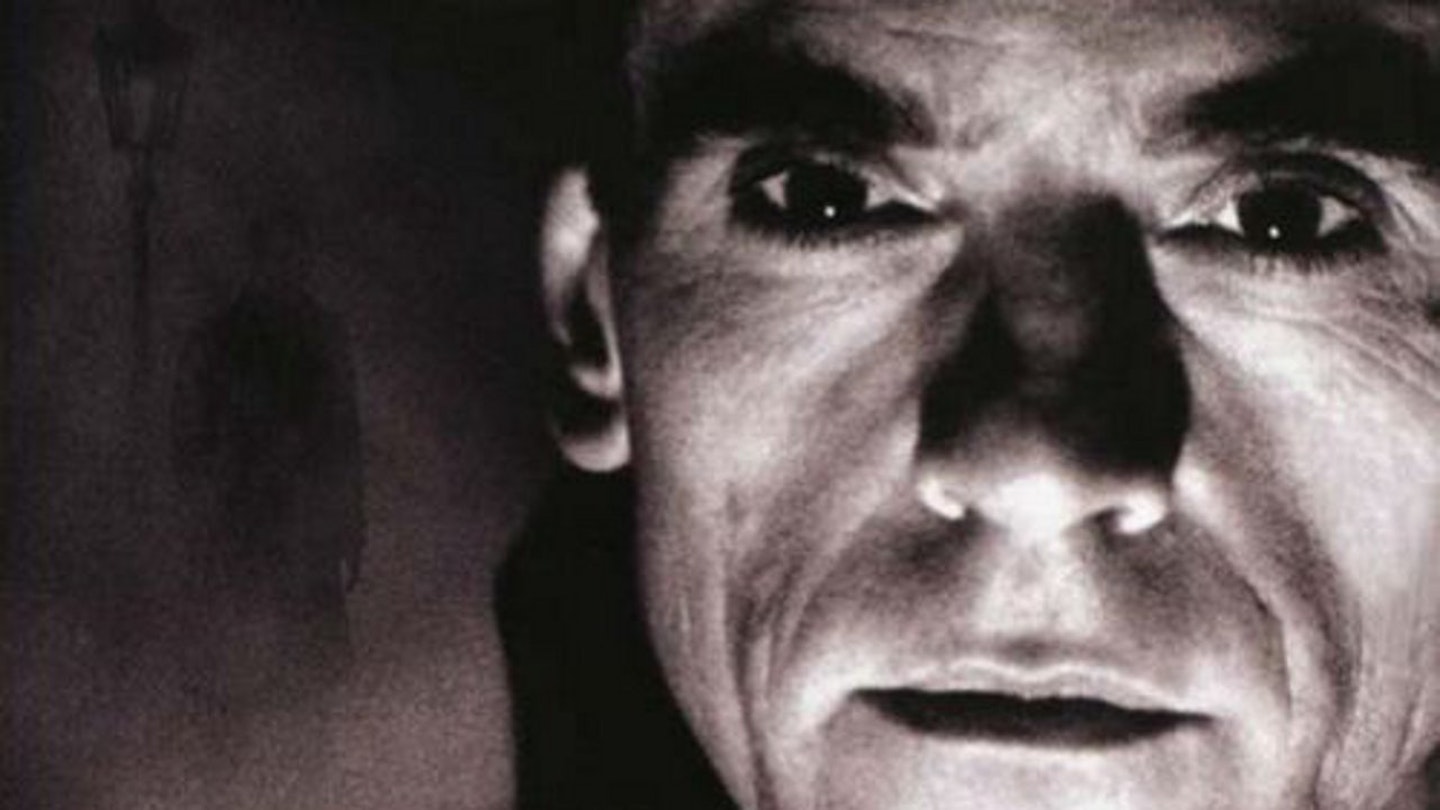

Actually, the film's terrible reputation is almost an advantage: while Soderbergh's debut was impossibly over-hyped, and, inevitably, disappointing, this comes on surprisingly strong and will, for many, be more satisfying. By day, a character called Kafka (Irons) toils in a Prague insurance office, saving his mind for the nights when he struggles to be a writer. When his only friend at the office is mysteriously murdered by a lobotomised zombie, Kafka is drawn into a conspiracy world alarmingly like the one he imagines. There is something suspect in films about authors which suggest they didn't have to go to the trouble of exerting creative talent since their lives provided them with all their material.

Here, however, the game is played in such exaggerated terms that it's forgivable: this in no way tries to be a biographical drama of an adaptation of a specific Kafka work, and, while it has comically horrid officials and such "Kafkaesque" concepts as the trial and the castle, is more a straightforward horror movie than a literary conceit. Irons wanders bemusingly through bodysnatching, as the script drops names like Murnau and Orlac to evoke German Expressionist cinema of the 20s, but the on-location black-and-white gothic of Prague and studied period details are more reminiscent of the Hammer Horrors of the late 50s. It even has a sequence shot in odd-looking colour and a parade of distinguished actors as jovially sinister suspects