Hereditary is not for the faint of heart. Honestly, we really mean it. But not in the sense that it might loudly jump-scare you into cardiac arrest. Ari Aster’s feature debut has its thorax-tightening shock moments, but they are rare (and all the more effective for it). Primarily, it takes the crawling-dread approach to horror, often serving up its most chilling shriek-treats before you even notice they’re right there in front of you.

One scene, for example, presents a character in the gloom of a midnight-shrouded room. As they sit up in their bed, carefully positioned in the lower left of Asters’ frame, you know right down to your bones that something isn’t right here. But you’re not seeing it. Then, perhaps, someone sitting nearby you will gasp, their sudden inhalation flagging they’ve spotted it before you. You look closer, your eyes darting around the frame’s dark edges and darker corners. You kinda don’t want to. But you’re compelled to. And then. Oh. Ohhh no. You see… It.

It’s all presented with gorgeous Kubrickian precision and elegant trompe-l’oeil techniques.

Aster might be a first-time writer-director, but he is clearly a natural-born master of horror. Otherwise, we can only assume that The Wicker Man was playing on loop in his maternity ward, that he effectively grew up in Room 237 of the Overlook Hotel and visually mainlined Hideo Nakata’s Ringu throughout his teen years. We wouldn’t be surprised if his mother’s name is Rosemary, either.

Hereditary wears its influences well, feeling inspired rather than derivative. Aster plays with a lot of recognisable ideas and tropes, but moulds them into something that hits you with minty-death freshness. There are pagan symbols and invocations. There are candle-lit séances. And as we already mentioned, there are terrible, terrible things lurking in those shadows. But he wraps it all up in a slow-burn story that plays on familiar insecurities — primarily the question of who to blame for our shortcomings: our parents? Ourselves? Or… something else?

It’s all presented with gorgeous Kubrickian precision and elegant trompe-l’oeil techniques, from a creep-zoom opening into the room of a model house (which then imperceptibly, unsettlingly transitions into the real thing), to the long, single-take glides around the Graham family’s harried home, to the reflection of hell-red lights in one character’s teary eyes, to the stab-quick cuts that lurch us from night to day and back again as Aster slices up time like a sushi chef.

A doomy, electronic pulse lurks low in the sound mix for most of the film, making you sit uncomfortably even when what’s happening on screen appears innocent or mundane. Aster never grants his audience any relief. There are no ‘oh it’s just a cat’ pressure releases in Hereditary. Everything is steeped in threat. Especially the places where you should feel safest.

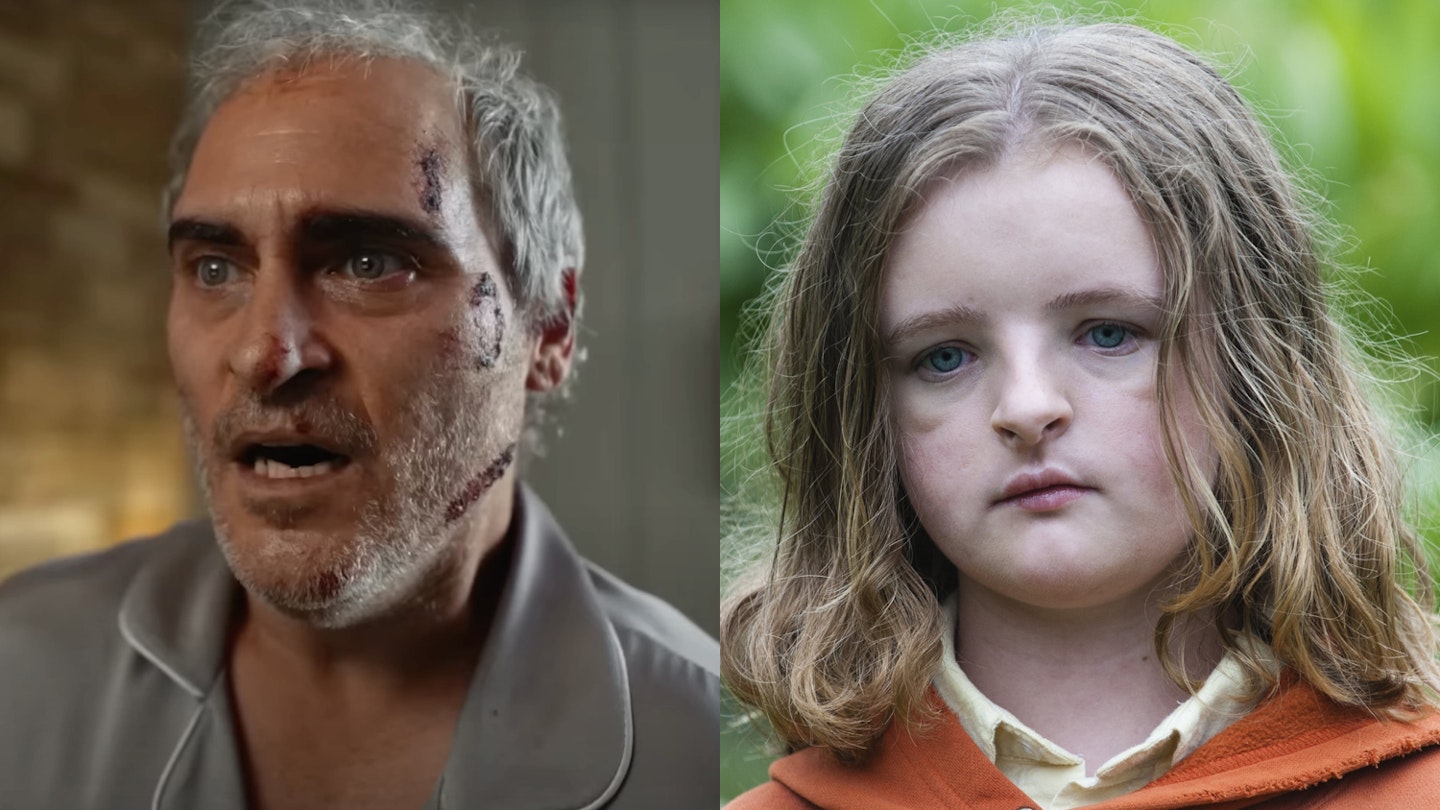

He’s marshalled an impressive cast, too. The youngest Graham, 13-year-old Charlie, is portrayed by newcomer Milly Shapiro in a way that somehow simultaneously elicits sympathy and deep-set disquiet. Alex Wolff (Jumanji: Welcome To The Jungle) sensitively portrays her older brother Peter as a teen who is, in a sense, un-coming of age — his traumas devolving him from bong-smoking slacker to squalling child, as you imagine they would anyone at his psychologically brittle stage of life.

Gabriel Byrne is suitably solid in the role of the steady, uninteresting, keeping-it-all-together (and failing) dad Steve. And as for Toni Collette in the lead role of Annie, Aster really puts her through the wringer, inflicting on his star-sufferer woes comparable with those suffered by both Essie Davis in 2014’s The Babadook and Ellen Burstyn in The Exorcist. Combined. Her screen-filling, straight-to-camera looks of sheer, unfiltered terror will likely stay with you for as long as many of Hereditary’s other scares. Which are numerous, relentless and never less than insomnia-invitingly intense.