In the era of President Trump, the time for subtlety is over. And considering Blumhouse’s schlocky action-horror Purge franchise wasn’t exactly understated to begin with, The First Purge wastes no time in projecting present-day headlines into full-blown American nightmares.

True to its title (no fake news here), Gerard McMurray’s prequel — the fourth film in the series — details the origins of that high-concept, low-logic premise: the New Founding Fathers Of America, a shadowy group of white authoritarians, propose an experiment in New York’s Staten Island district wherein all crime is legal for 12 hours. The location is chosen as it’s a low-income, majority-black neighbourhood, where the government expects frustrations over inequality to spark violence, and promises financial reward to residents who stay through the experience.

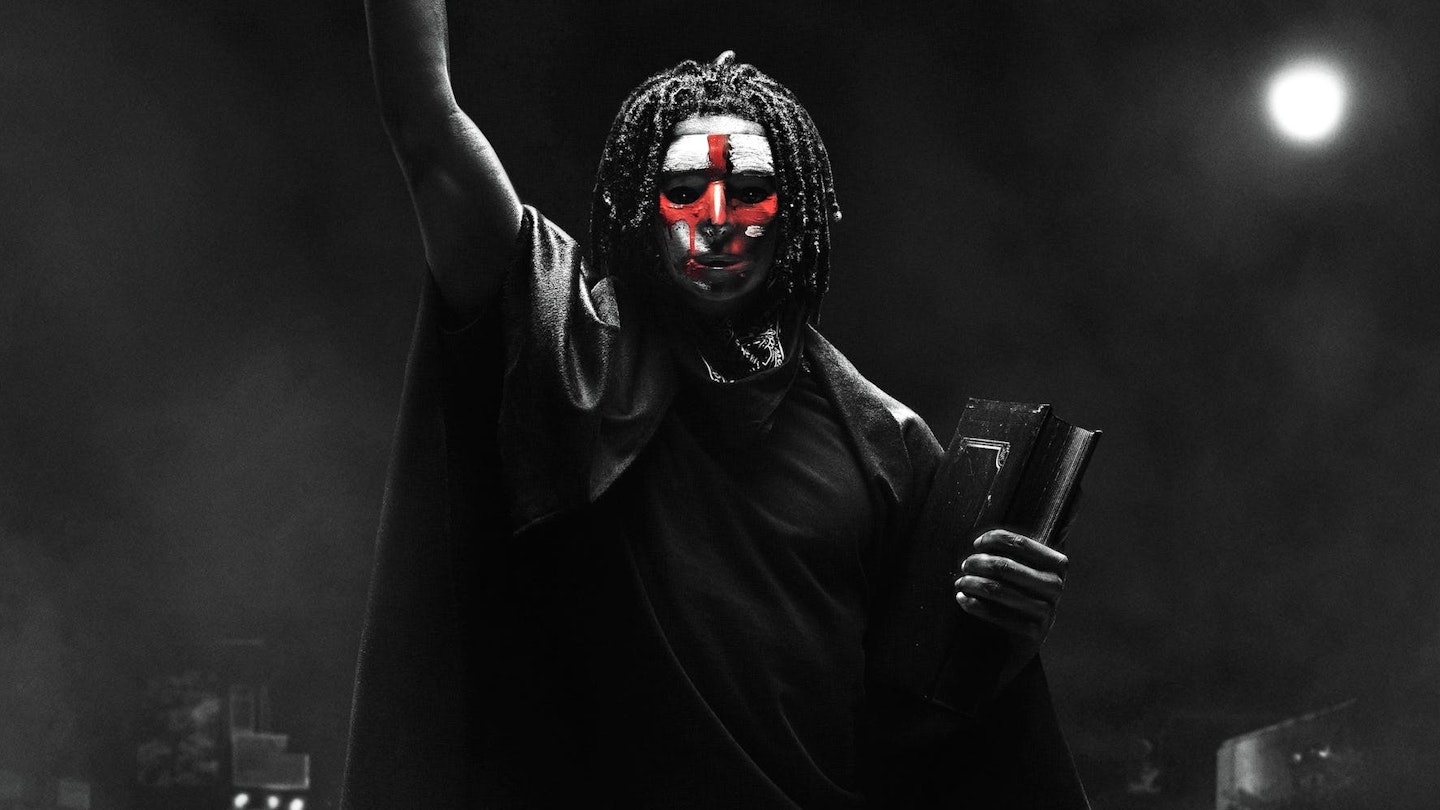

It’s in The First Purge’s set-up that McMurray does his best work, exploring similar themes of pent-up masculine aggression as his frat-hazing feature debut Burning Sands. While local drug lord Dmitri (Noel) tries to convince his eager male crew to lay low and not risk their lives over the night, young Isaiah (Wade) sees it as his opportunity to prove himself and take revenge on Skeletor (Rotimi Paul), the psychopathic druggie who attacked him. It soon becomes clear that Isaiah isn’t cut out for killing, and he’s forced to find his way back to safety while Skeletor fashions himself into a real-life Freddy Krueger with needles strapped to his fists.

If the film’s first act is perceptive about the intersections of race, class, and gender that make America so politically volatile, the Purge action itself is less assured — the jump-scares are thin, confrontations light on tension, and there are hokey elements such as the light-up contact lenses that give Purge participants glow-in-the-dark glares. James DeMonaco’s screenplay struggles to choose one primary plot thread, shifting focus midway through from Isaiah — an engaging breakout performance from Brit actor Joivan Wade — to Dmitri, who tools up to take on the regime in an action-hero finale that, while crowd-pleasing, also uncomfortably suggests that more violence is the answer. Still, the plot is also peppered with strong ideas — the Purge kicks off with a massive block party because, since nothing’s illegal, the police can’t pull anyone over on false charges — and doesn’t outstay its welcome with a lean 97-minute runtime.

The exaggerated imagery of The First Purge — from its Nazi-fetish villains, to the sight of NFFA-sanctioned, KKK-hooded mercenaries driving into the neighborhood to incite more violence when the experiment doesn’t yield the expected results — might feel heavy-handed, painting in big, broad, lurid strokes. But at least it’s saying something about the state of America, as loudly as possible, to a large mainstream audience. The premise of the Purge is still bonkers — but as The First Purge proves, in the five years since the first film, it’s the real world that’s become less believable.