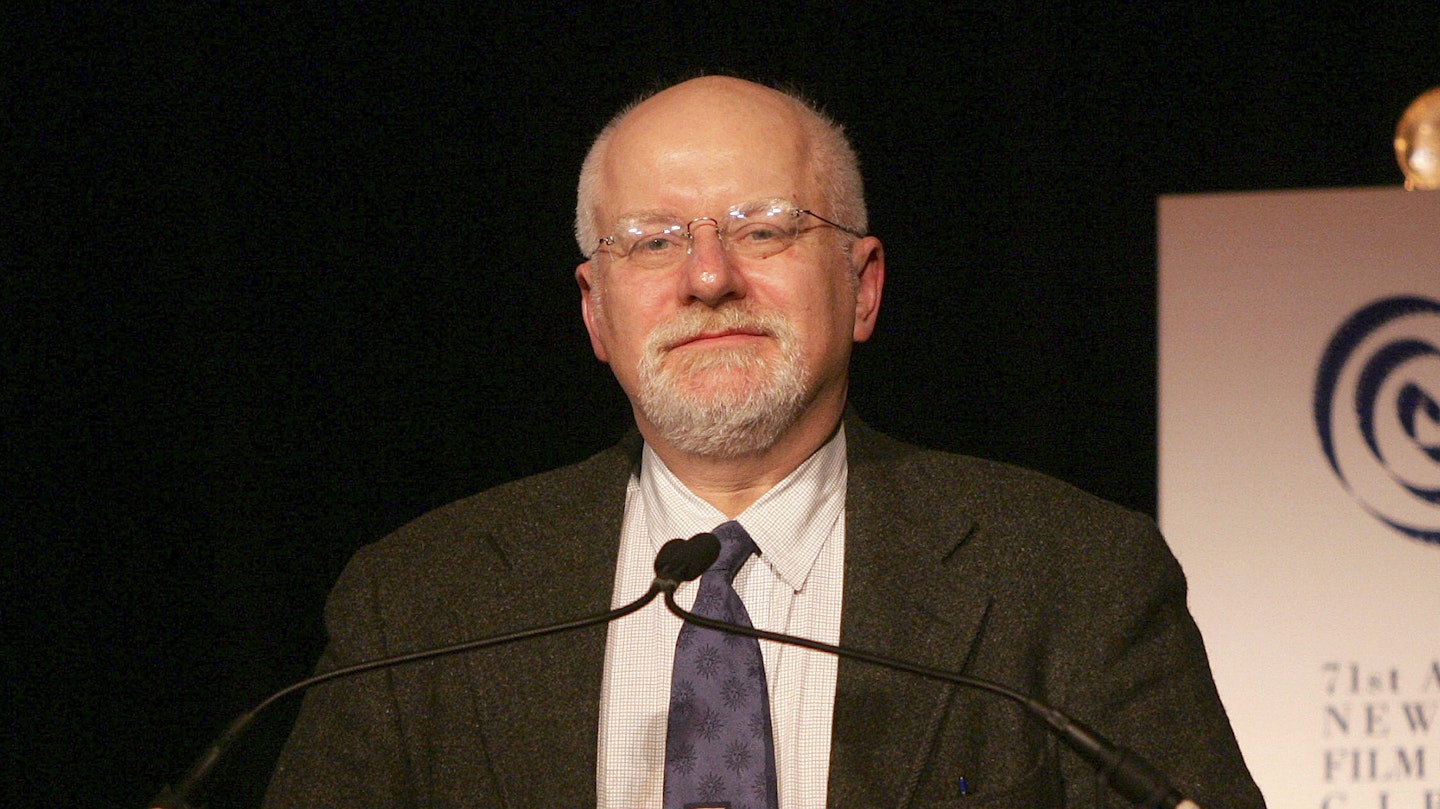

Chris Claremont wrote The Uncanny X-Men and many spin-off titles between 1975 and 1991. For Empire's X-Men: Apocalypse cover story we asked him to pick five key storylines in the characters’ evolution. This is an edited version of the full Q&A.

Len Wein and Dave Cockrum set up the new X-Men — notably Wolverine, Storm, Nightcrawler and Colossus — in a one-off special and then you took over as writer. What excited you about joining the series?

The most basic excitement was the opportunity to work with Dave Cockrum. He was an artist I’d admired for years and our imaginations were ridiculously simpatico. The whole goal with the first two-dozen issues was to keep everybody guessing as to what would happen next — to make it very, very difficult for them to take the series and the characters for granted.

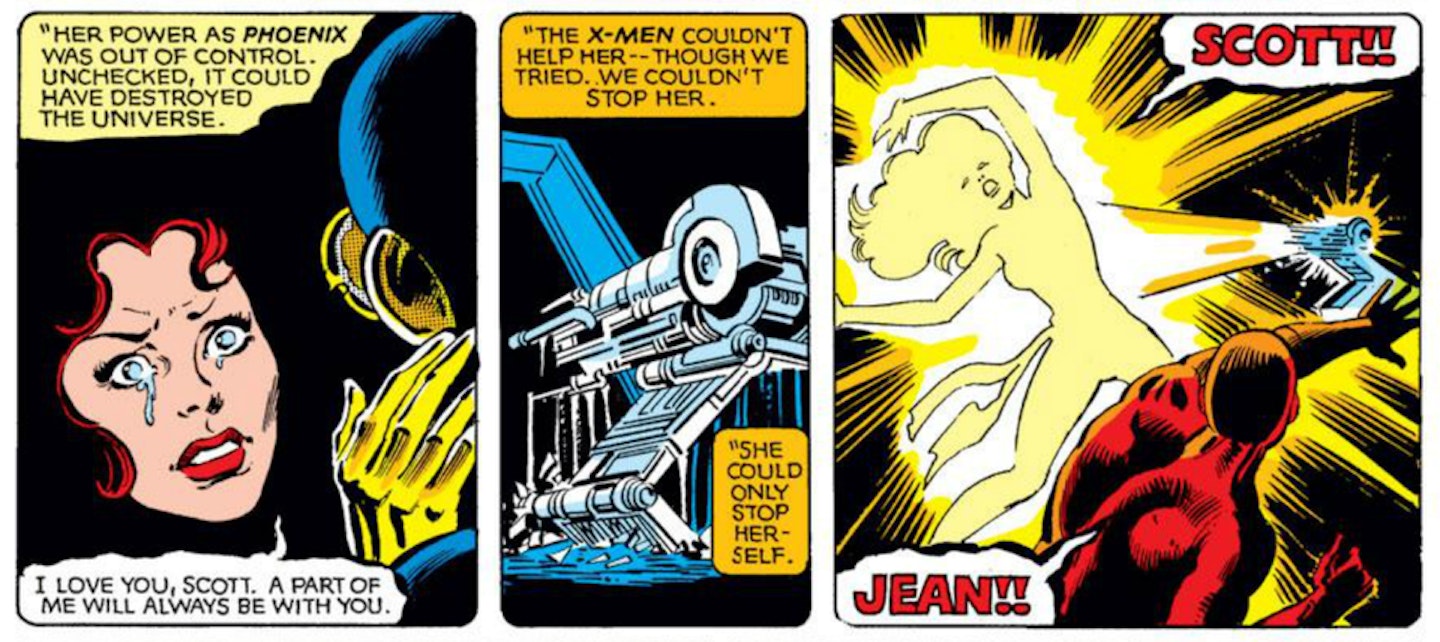

In the Dark Phoenix saga (#129-138) you turned Jean Grey into a planet-destroying superbeing and then killed her. What led to such a bold decision?

It was the comic-book studio system done absolutely right. I think subconsciously we were heading towards a tragic ending, but neither [artist] John Byrne nor I really wanted to go there because Jean was one of our favourite characters and her relationship with Scott [Summers] was the second oldest romantic relationship in the Marvel universe. There had to be a happy ending, we thought. But Jim Shooter, the editor-in-chief, read the issue and realised, "Hang on, she’s just committed planetary genocide and she gets away with a slap on the wrist!" That, he felt, was a little inappropriate. My decision was she dies. And because of the era — no internet, no fan magazines posting top secret information — we caught everybody by surprise.

Because there was no internet then, we caught everybody by surprise with Jean Grey's death. We got death threats.

How did the fans react?

Oh, we got death threats. Frank Miller and I kept notes because Frank got death threats when he killed off Elektra and I got death threats when I killed off Phoenix. Frank even contacted the NYPD to ask, "Should we take this seriously?" And they said, "Well, if somebody shoots you, yes." We were going to try as hard as possible to make it stick: she died. She’s not coming back. End of story. Of course, that got upended by ideas that the editors and the company felt were appropriate, but for three or four years we established for the readers that our heroes were at legitimate risk. You couldn’t sit back and say, "Well they’re heroes, everything’s going to come out all right at the end." Not necessarily.

Now when a character dies in a comic book you know they’re coming back…

Every time they die now everybody starts the countdown to when they’re coming back!

A major theme of your X-Men stories was using mutants as a metaphor for other persecuted groups. Where did that idea come from?

I went to Israel for two months in 1970 and worked on a kibbutz. It affected me on levels that I hadn’t anticipated, working on a daily basis with people who were actual survivors of the Holocaust. You’d see military patrols going by every day. We would have armed volunteers walking around the property all night. It brought home international conflicts on a very personal level.

With the X-Men, were you thinking only of antisemitism or racism and homophobia as well?

It was blended in. There’s a lot of talk online now that Magneto stands in for Malcolm X and Xavier stands in for Martin Luther King, which is totally valid but for me, being an immigrant white (Claremont was born in England), to make that analogy felt incredibly presumptuous. An equivalent analogy could be made to [Israeli prime minister] Menachem Begin as Magneto, evolving through his life from a terrorist in 1947 to a winner of the Nobel Peace Prize 30 years later. That evolution was something I wanted to apply to the relationship between Xavier and Magneto. It’s an evolving 150-issue arc: Magneto’s resurrection as an angry, anti-human, pro-mutant terrorist. In #150 he lashes out and the person that gets hit is Kitty Pryde, a 13-year-old kid. His shattering realisation is: "What kind of monster have I become? Has what the Nazis did to me in the Shoah made me a Nazi?" Ultimately, my goal for the character was that he would come full circle and become Xavier’s heir, as headmaster of the school and leader of team. For me he was a much more fascinating character because of his flaws and there was always a risk that he might fall from grace. Instead, they felt Magneto was far too valuable a character as a straight villain.

Every time a comic-book hero dies now, everybody starts the countdown to when they’re coming back.

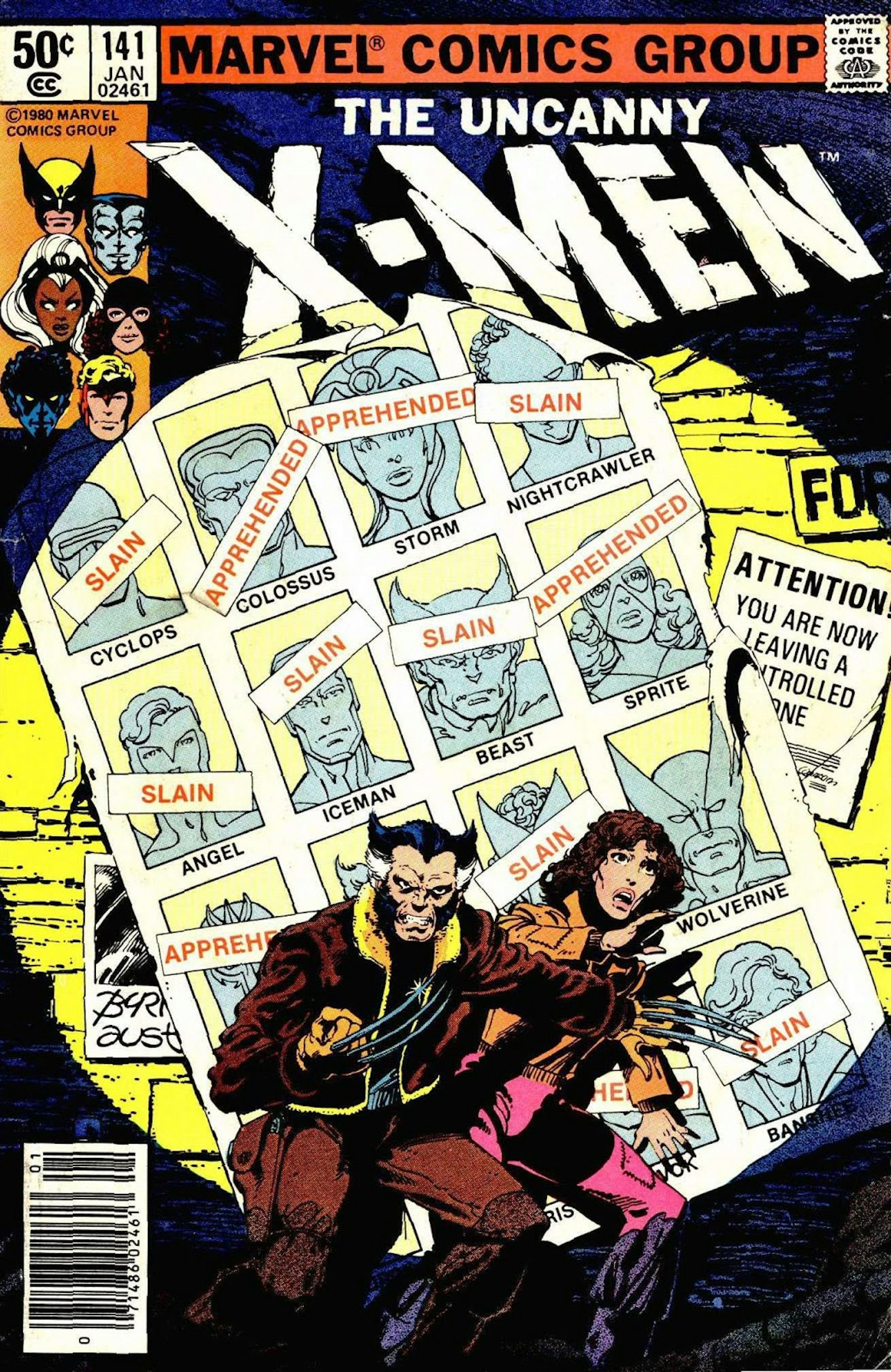

Of course, you took the idea of mutants facing genocidal hatred to extremes with Days of Future Past (X-Men #141-142), where mutants are outlawed and murdered by the Sentinels…

The idea was to show our heroes why their fight is so necessary. There is a tragic cost to failure. The line we always used to describe these characters was ‘feared and hated by the world they are sworn to protect’. Their struggle is not simply to defeat the bad guys; it is to establish themselves as credible, honourable fellow citizens of the planet. The idea with Days Of Future Past was this is what’s lying in wait if you falter. If you ever needed a reason to try and try again, this is it.

What was it like killing off all these beloved characters in the future?

Crass as it may sound, it was incredibly cool. We were getting classically Greek. The weird thing for me is I’m sitting there in the '80s writing about the Mutant Control Act and here we are in the second decade of the 21st century with the Patriot Act, listening to presidential candidates talk about building walls to keep people out: who’s acceptable and who isn’t. It’s very creepy. I feel like I’ve walked down this road before.

Crossovers between titles became a big part of the X-Men universe. How did they start?

The Asgardian Wars (1985) that I did with Paul Smith and Art Adams was our first legitimate graphic novel. It’s 250 pages! In terms of page count it’s a real novel and we take the audience everywhere. What a lot of people forget is we did Days Of Future Past in 38 pages. The Marvel rule was that ideally a story should be one issue. If it’s really good, two issues. If it’s the arrival of Galactus, okay, you can go to two-and-a-half. Brevity was very much the soul of wit back then. The practical reality was if you hit what we called a 'FUBAR' — something that didn’t work — you were out quickly enough so that you weren’t stuck with the story and the readers didn’t get bored and go somewhere else. This way if you made a mistake, wait three weeks and we’ll fix it. That is not a bad paradigm to follow.

The Asgardian Wars involved two teams and two special editions but the crossovers got a lot more ambitious. Was it hard to keep the narrative plates spinning?

It was basically mine and [editor] Louise Simonson’s fault because we had the bestselling comic in the industry and we had this idea to do a team-up between the New Mutants and the X-Men. Then Louise’s husband Walter Simonson, who was drawing Thor, asked if he could join in. The next thing you know we had the Mutant Massacre (#210-213 and other titles). Our feeling was at that point there were too many mutants and we wanted to thin down the herd. For me, one of the things that makes the X-Men so crucial is they are relatively small in number but they have the potential to have a tremendous impact on the society around them.

Does having too many mutant characters make it harder to tell smaller stories about individual X-Men?

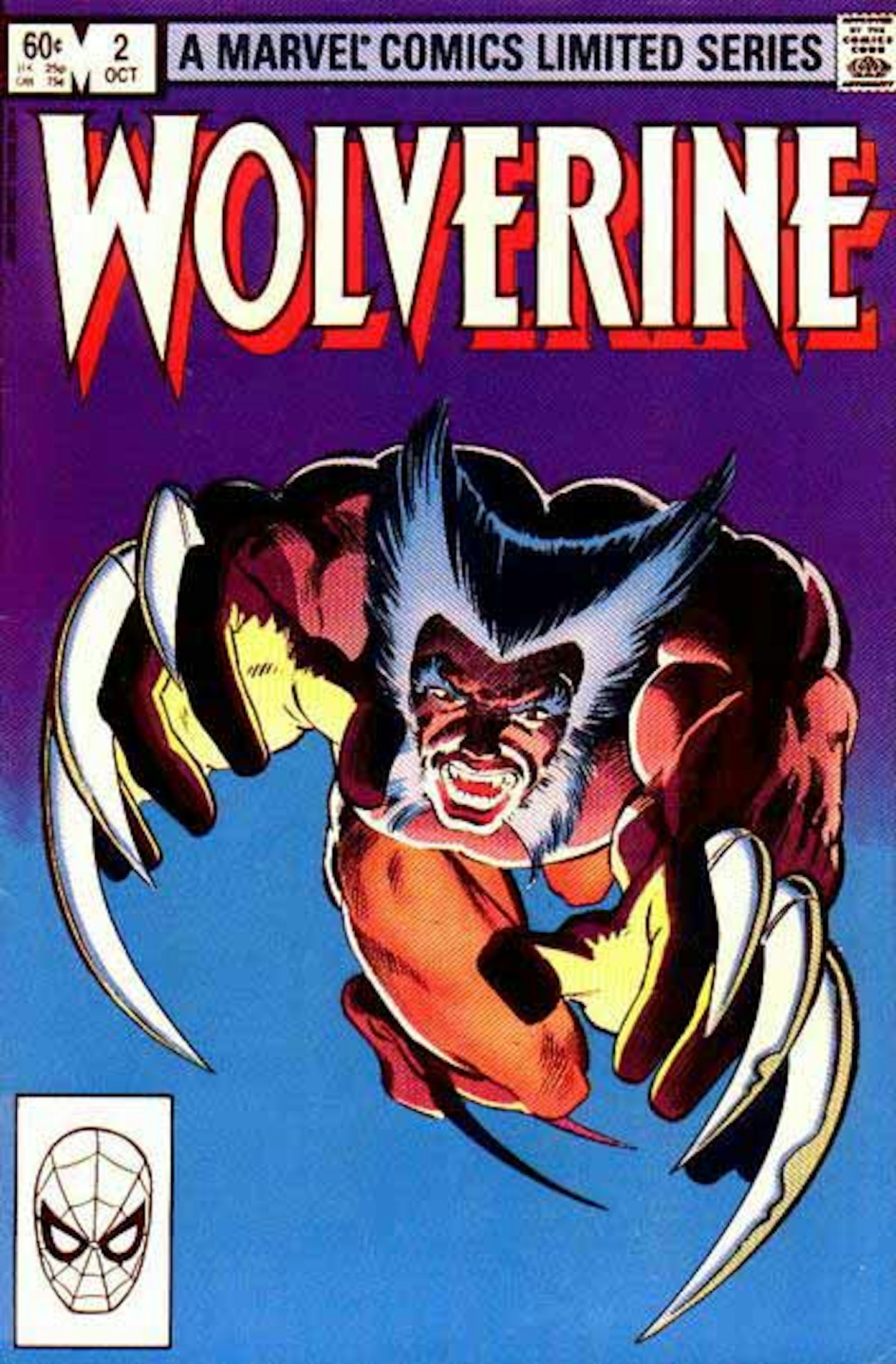

Well, you get lost in the multitude. The thing that I’ve always enjoyed about Wolverine derives from a story I heard when I was a student actor. When Camelot was on Broadway you had this crowded stage and, upstage right, Richard Burton walks in as Arthur. Every eye just went — whammo! — right to him, because he had such innate starpower. He didn’t have to do anything. He was there. And once he was there, you looked at him because you knew something was going to happen. And that’s the thing with Wolverine: no matter where he is on the page, he’s always where your eye goes.

No matter where Wolverine is on the page, he’s always where your eye goes.

Wolverine was the first X-Man to get a solo title: a four-issue 1982 series drawn by Frank Miller...

For me that’s the best example of getting on, saying your piece, getting off and telling what turns out to be a lasting, memorable story: boy meets girl, boy loses girl, boy meets bad girl, boy gets good girl back. And, oh yes, along the way he has to kill her father! That was fun because it got to the heart and soul of Wolverine: the conflict between the animal side, which is raw passion, and the other half, which is a desire to be as purely human and under control as you will see in any Japanese samurai’s apartment.

Wolverine became the fans’ favourite. Were you especially fond of him?

You have to remember all of this is a partnership. Dave Cockrum’s favourite character was Nightcrawler. The character that John Byrne bonded was with Logan, partly because they were both Canadian, partly because they both felt like outsiders. So that was him moving to the fore. I tended to be more interested in Ororo [Storm], Kitty and Jean. I wasn’t interested in doing people who were just boyfriends or just girlfriends. I wanted them as full characters. I would hope part of what brings the actors back is the opportunity to play richly textured characters that are more than just clichéd heroes. The whole point of the X-Men, for me anyway, is to look at them as people with this one little glitch that tends to screw up their lives more often than not. The essence is people trying to live their lives and realising along the way that they’ve made mistakes. It should never be just one set of skintights against another set of skintights.

There weren’t many strong female characters in Marvel comics in the '70s and '80s but the X-Men had plenty…

This goes back to Israel. There is nothing so disconcerting as sitting on a bus and having a young lady walk on with an Uzi flung over her shoulder. In 1970 you weren’t used to seeing someone you might ask out on a date packing hardware. So it’s taking that realisation and applying it to the fictional reality of the X-Men and seeing where it leads.

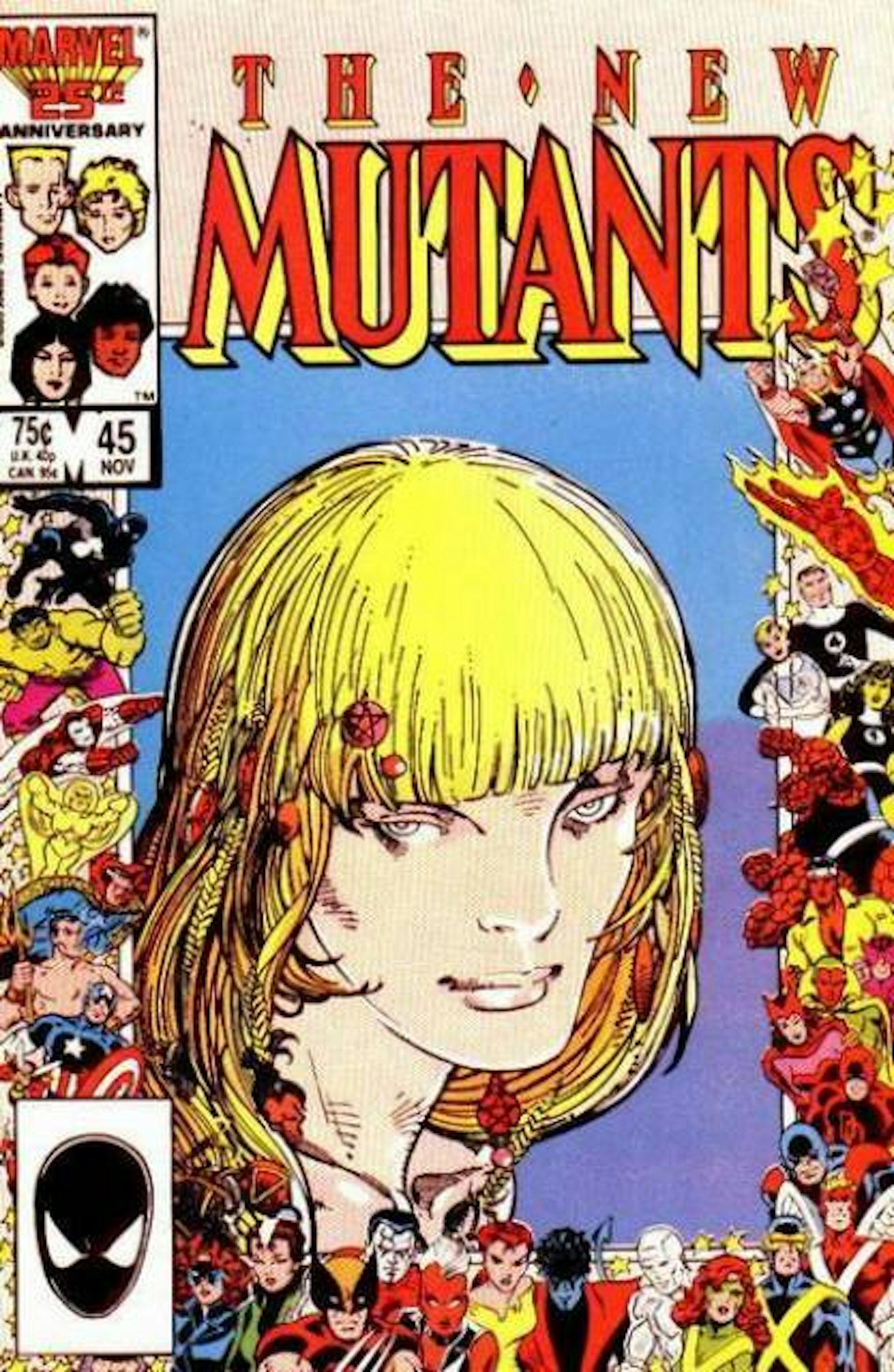

Alongside the X-Men, you wrote The New Mutants about Xavier’s young students. What’s your favourite New Mutants story?

One that I’m proud of is We Were Only Foolin’ (#45), where a young mutant comes to Salem Centre. It goes wrong and he feels more and more alone. At the end of the story he takes his own life. We got a lot of letters from kids: "I’ve been in that position." "I have friends in that position." Anyone can write a story about people hitting people. That’s the easiest thing there is. But to try to make it meaningful and relevant to the readership, that’s a gamechanger. The X-Men are fun but they’re grown-ups. They’re already set. The kids are the fungible ones. They’re making mistakes and they don’t know quite what they’re doing. This adventure might lead them to Asgard, the next one might lead them to someone committing suicide. It’s like seeing the evolution of Prince Hal through Henry IV 1 & 2, leading up to Henry V. It’s about growing and learning and taking responsibility.

You can do anything with the X-Men, can’t you?

That, for me, is the joy of comics: you can throw in anything, anywhere, any way. All of the fun of a quarter-billion-dollar film project without any of the budgetary constraints. The only limitation is the imagination of the two prime creators: the writer’s ability to come up with an idea and the artist’s ability to bring it to life. It’s been wonderful.

X-Men: Apocalypse is out in the UK on May 18. Head here for Empire's primer. Read our full coverage of X-Men: Apocalypse in the latest issue of Empire magazine.